My Year in Writing 2025

November 29, 2025

This is the time of year—between my birthday and year’s end—when I take stock of my writing life over the past 12 months. A trend that’s continued this year: I’ve continue to be very Berkshire-focused as we approach the fourth anniversary of our move up here. As I told one of my students at Berkshire Community College this semester, where I’ve been teaching Principles of Marketing, filling in for a professor on her sabbatical, “This is my time to give back and go hyperlocal…”

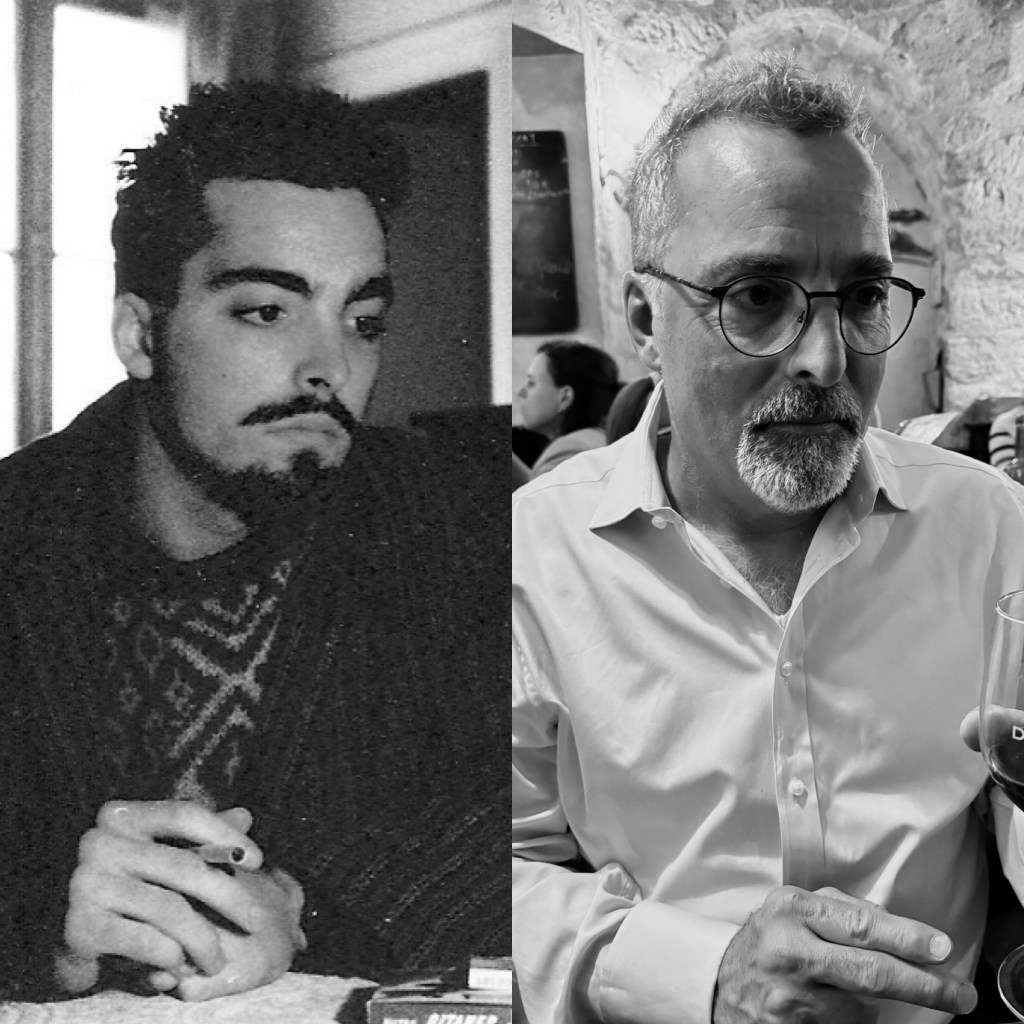

I’ve also continued to write for Berkshire Magazine—eighteen in total and sometimes as many as 4-5 articles per issue (!), causing me to joke with my editor, Anastasia Stanmeyer, “Do you have any other writers?” In addition to having the cover story in one issue this year, Anastasia generously wrote about me in her editor’s note in the Fall issue accompanied by this photo.

I’m still shopping around my book of essays, The Others in Me: On the Azores & Ancestry, Poetry & Identity, and am building a new series of essays about life on our little beaver pond in the Berkshires, which I’m calling “To Learn Attention: Encounters in the Anthropocene Backyard,” several of which were published earlier this year.

While we didn’t get to the Azores for the second year in a row—something I hope to remedy in 2026—we had a wonderfully inspiring trip to Paris in late March-early April. Overall, it’s been a productive year. Here are some of the highlights:

“A Modern Log Cabin: Industrial Chic Meets Rustic Warmth,” in Berkshire Magazine, Spring 2025

“Betting Big on the Outdoors: Paul Jahinge Leads the State’s Outdoor Recreation Vision” (profile), in Berkshire Magazine, Spring 2025

“Matt Rubiner: An Unconventional Path to Cheese Mastery” (Q&A) in Culture: The word on cheese, Spring 2025

“Ancestral Echoes: Exploring Aracelis Girmay’s An Experiment in Voices,” in Berkshire Magazine, May-June 2025

“Poetic Sweat: Bill T. Jones and His Company Return to Jacob’s Pillow” (profile), in Berkshire Magazine, May-June 2025

Attended MAPS’ Psychedelic Science Conference in Denver, CO, reporting on several future stories and features. (June)

“My Wife Gave Me Magic Mushrooms For My 60th Birthday. It Transformed My Life In Ways I Never Expected,” HuffPost, June 2025 (The response to this piece was absolutely amazing. My editor at HuffPost wrote that something like 250,000 people read it the first weekend it was published, with “an average read time of 2:46 minutes (the site average for a story is 0:40, so to get folks to stay on your piece for close to three minutes is AMAZING and means that most people read all the way through… a huge feat in today’s ‘click in and click out’ digital world).” I heard from people all over the country: people who needed to hear the message of my tory and who now have hope that there’s something out there that may be able to help them. I feel especially blessed to have published this piece this year.)

Psychedelic Healing in Practice: A conversation with Scott Edward Anderson on AdvisorShares’ AlphaNooner podcast. (July)

Opinion: Don’t let New Bedford erase its Portuguese soul – “ The proposed closure of Casa da Saudade isn’t just a budget cut, it’s cultural erasure. The library has been the beating heart of Portuguese American identity in one of America’s most Lusophone cities.(Opinion), in New Bedford Light (July)

“A Building That Dances: The Reimagined Doris Duke Theatre Takes Flight,” feature in Berkshire Magazine, July 2025

“A Landmark Farewell: Stephen Petronio in his company’s final bow this summer at Jacob’s Pillow” (Q&A), in Berkshire Magazine, July 2025

“Paul Elie on Literature, Faith, and the Culture of Encounter” (Q&A), in Berkshire Magazine, July 2025

“A Homecoming: Richard Blake Creates Great Barrington’s W.E.B. Du Bois Monument” (profile), in Berkshire Magazine, July 2025

“A Conversation Before the Conversation: A talk with Jayne Anne Phillips ahead of her visit to the Mount” (Q&A), in Berkshire Magazine, July 2025

“Threads of Time: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Returns to Jacob’s Pillow After 62 Years” (Cover story), in Berkshire Magazine, August 2025

“The Power of Words: The WIT Literary Festival Returns with a Bold Call for Civic Engagement Through Literature,” in Berkshire Magazine, August 2025

Four essays from “To Learn Attention: Encounters in the Anthropocene Backyard” in La Picciolétta Bárca, August 2025

“From Investment to Impact: Mill Town’s Blueprint for a Stronger Pittsfield and Berkshire County” (feature), in Berkshire Magazine, Fall 2025

“A Recipe for Community: Williams College’s Log Lunch brings people together over food and ideas,” in Berkshire Magazine, Fall 2025

“Making Public Lands Welcome to All: An interview with newly appointed DCR Commissioner Nicole LaChapelle” (Q&A), in Berkshire Magazine, Fall 2025

“Cheesemaking Tradition Meets Innovation in the Azores” (feature) in Culture: The word on cheese, Fall 2025

Featured poet in reading at Hot Plate Brewing Company in Pittsfield, along with Susan Buttenweiser, Anna Lotto, Matthew Zanoni Müller, and Lara Tupper. (September)

“(Take) Home (or Dine In) for the Holidays: Your guide to Thanksgiving Dining in the Berkshires” in Berkshire Magazine, Holiday 2025

“Ice Dreams Really Do Come True: Community, Competition, and Cold Weather Fun in the Berkshires” (feature) in Berkshire Magazine, Holiday 2025

“Giving Back Locally: Supporting Organizations that Strengthen Our Community” in Berkshire Magazine, Holiday 2025

“Driving Community: Berkshire Auto Dealerships are Expanding, Thriving, and Staying True to Their Roots” (feature) in Berkshire Magazine, Holiday 2025

I also started working on a new sequence of poems, “Aquapelagos,” exploring themes of islands as ancestral territories and identity markers. We’ll see where that goes…

And I continued to curate and host the Berkshire Nature Talk Series at West Stockbridge Historical Society. We had four programs this year featuring Nicaela Haig of MassAudubon, Chip Blake on the birds of the Berkshires, Thomas Tyning on reptiles and snakes, and Brian Donohue on building with local forests. The program was funded in part by grants from the Alford-Egremont, Richmond, Stockbridge, and West Stockbridge cultural councils, local agencies which are supported by the Mass Cultural Council, a state agency.

A productive year. Hope to keep getting my fix in 2026!

—SEA

My Year in Writing 2024

December 9, 2024

This is the time of year—between my birthday and year’s end—when I take stock of my writing life over the past 12 months. A trend I’ve noticed this year is that I’ve become very Berkshire-focused as I approach the third anniversary of our move up here. I see that as a good thing; it means I’m digging into our community more and focusing on what’s closest to me.

I’ve also had the opportunity to explore more magazine writing—features, profiles, and interviews—through my work with Berkshire Magazine, which has allowed me to engage with and write about Michael Pollan, Mark C. Taylor, Camille A. Brown, Forrest Gander, and Ruth Reichl, among others. Thanks, Anastasia Stanmeyer!

And the Azores continues to be a focus—even though we didn’t return to the islands this year for the first time since 2021. We’ll have to change that in 2025! Overall, it’s been a productive year. Here are some of the highlights:

“Seeking My Roots Through a Painter’s Eyes” (essay), in Revista Islenha, Issue 73, in Madeira, Portugal. (January)

Led a writing workshop at Herman Melville’s Arrowhead titled, “Cultivating Deep Attention,” helping participants explore the art of profound concentration and how it can enhance their writing process and equip them with the tools and mindset needed to harness the power of deep attention in their writing journey. Workshop (February)

Launched “Berkshire Nature Talk Series” at West Stockbridge Historical Society with Leila Philip, author of Beaverland, kicking off the program. Featured three more talks throughout the year on birds, bears, and mushrooms. (February)

“A Philosopher’s Secret Garden: Mark C. Taylor and His Landscape of Ideas,” (lecture/presentation), delivered at “After the Human: Thinking for the Future,” UCSB Humanities & Social Change Center (March)

Featured poet at the first annual Poesia: A Celebration of Portuguese Poetry, Culture, & Fall River Poets, presented by Viva Fall River and Newport Poetry, at the Gates of the City, Fall River Heritage State Park, and the Fall River Visitors Center. (April)

“The British Invasion: The Royal Ballet Takes Over Jacob’s Pillow,” (article), Berkshire Magazine (May/June)

“Keep on Trocking: Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo Kicks Off Jacob’s Pillow 2024 Season,” (article), Berkshire Magazine (May/June)

Creative nonfiction mentor, Adroit Journal Summer Mentorship Program, mentored two students for the third year. (June-July)

“Cathy Park Hong: “On Minor Feelings, and writing poetry & prose,” (Q&A), Berkshire Magazine (July)

“Emily Wilson: On Translating Homer—and his lessons for today,” (Q&A), Berkshire Magazine (July)

“A Philosopher’s Secret Garden: Mark C. Taylor’s Landscape of Ideas,” (profile), Berkshire Magazine (July)

“Storytelling Through Dance: Camille A. Brown’s Vision & Voice,” (profile), Berkshire Magazine (July)

Hosted a Poetry booth at West Stockbridge Zucchini Festival where festival goers wrote “zucchrositc” poems – yes, acrostics using the word zucchini! (August)

“Getting Back to the Garden: Michael Pollan’s Long, Strange Trip,” (profile), Berkshire Magazine (August)

“Jennifer Egan: On The Candy House, storytelling, and genre,” (Q&A), Berkshire Magazine (September)

“Every Meal is a Story: A Peek into Ruth Reichl’s World of Food,” (profile), Berkshire Magazine (September)

“Lenox Rising: A Berkshire Town’s Resilience and Renewal,” (article), Berkshire Magazine (September)

Catalog essay for “NEXUS 2.0.1: Contemporary Landscape Paintings by Paul Paiement,” Ethan Cohen Gallery, NYC, October 10-November 23. (October)

“Prayer House,” (poem), Speaking for Everyone: An Anthology of “We” Poems (October)

“Six Poems by Pedro da Silveira from A ilha e o mundo,” (translations), Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, (October)

Featured Author of the Month, Casa da Saudade Branch Library, New Bedford Free Public Library, New Bedford, MA (October)

My poem, “Wanting,” reprinted in Poetry is Bread: The Anthology, edited by Tina Cane, published by Nirala Press, India (October)

“Massachusetts Voter Endorses Ballot Measure #4,” (Op-Ed), Lucid News (November)

“Letter to America: The psychedelic renaissance,” (essay), Terrain.org (November)

“The Power of Listening: Forrest Gander’s Poetry of Memory and Place,” (profile), Berkshire Magazine (November)

“A Massachusetts Voter Reflects on the Failure of Psychedelics Ballot Question 4,” (Op-Ed), Lucid News (December)

“First Impressions of the Açores,” (essay), Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies (December)

A productive year, indeed—hoping to keep it alive in 2025!

—SEA

National Poetry Month 2024, Week Three: Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s “Descobrimento”

April 22, 2024

This Thursday marks the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, whereby the people of Portugal overthrew the dictatorship under which they had lived for forty-eight years. I have previously shared my translation of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s poem of the revolution, “25 de Abril” (“25th of April”). Sophia was born in Porto in 1919, she died in 2004 at the age of 84 and is now buried in the National Pantheon in Lisbon, an honor recognizing her as one of Portugal’s greatest poets.

Her work often explored themes of nature, particularly the power and mystery of the sea. Indeed, she can be considered a poet of the sea. One poem that encapsulates her maritime inspiration is “Descobrimento” (“Discovery”). In “Discovery,” Andresen paints a vivid, almost surreal portrait of the ocean through metaphor and visceral imagery. She writes of “An ocean of green muscles/ An idol with as many arms as an octopus/ Incorruptible chaos that erupts/ And orderly turmoil…” [my translation]. This strange yet mesmerizing depiction captures the paradoxical nature of the sea — its turbulent, ungovernable force coexisting with an inherent rhythm and pattern.

The sea represented many things for Andresen beyond its literal presence. As a dedicated Hellenist, she found inspiration in ancient Greek mythology and often blurred the lines between the Atlantic Ocean of her Portuguese homeland and the Mediterranean. The sea became a symbol of renewal, eternity, and the mysteries of life and death.

Her reverence for the ocean likely stemmed from her childhood spent along the coast in Porto, watching the ebb and flow of the tides. The poem evokes her early, formative experiences at Praia de Granja, a beach south of Porto that shaped her poetic vision.

In “Discovery,” Andresen seems to be urging the reader to explore the depths of the ocean and surrender to its “incorruptible chaos.” The sea is both menacing with its crashing waves and comforting in its ceaseless cadence. By wading into those waters, perhaps we can access greater truths about ourselves and the world around us.

With her luminous language and profound naturalism, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen invites the reader to discover the ocean anew through her transcendent poetry. “Discovery” reminds us that the seas contain not just thrilling adventures and discoveries, but insights into the very essence of our existence.

Here is my translation of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s “Descobrimento”:

Discovery

An ocean of green muscles

An idol with as many arms as an octopus

Incorruptible chaos that erupts

And orderly turmoil

Dancer twisted up

Around the outstretched ships

We cross rows of horses

Who shake their manes at the trade winds

The sea suddenly became too young and too old

To show the beaches

And a people

Of newly created men still clay-colored

Still naked, still dazzled

—

Here is the poem in its original Portuguese:

Descobrimento

Um oceano de músculos verdes

Um ídolo de muitos braços como um polvo

Caos incorruptível que irrompe

E tumulto ordenado

Bailarino contorcido

Em redor dos navios esticados

Atravessamos fileiras de cavalos

Que sacudiam as crinas nos alísios

O mar tornou-se de repente muito novo e muito antigo

Para mostrar as praias

E um povo

De homens recém-criados ainda cor de barro

Ainda nus ainda deslumbrados

–Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen

From Obra Poética III, published by Caminho, Lisboa

To hear Sophia read her poems in 1985: https://www.loc.gov/item/93842563/

My translations of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, along with several other Portuguese poets, appear in my book Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations (Shanti Arts, 2022), available through this link or wherever you buy books.

In December 1994, I attended a poetry reading at Poets House in New York by two Portuguese poets, Nuno Júdice and Pedro Tamen, along with the translator, Richard Zenith. Little did I know that this event would have an impact on the profound journey into my ancestral roots in Portugal and the Azores.

After my Portuguese grandfather passed away in September 1993, I was at a loss to uncover our family’s history, which he had been reluctant to share. Hearing Júdice and Tamen read their poems in Portuguese the following December was a revelation of sorts—here were real, live Portuguese poets speaking the language of my ancestors.

The dearth of first-hand accounts and available source materials kept me from learning my family’s Portuguese Azorean history for many years and, frankly, life got in the way of digging deeper. When my father died in 2016, I realized that all my family’s histories were available to me, except one part—the Portuguese. By then, Ancestry.com had made many research materials available online for the first time, and a group of Azorean Genealogists gathered on a listserv to share information, leads, and help translate documents from the Azores, much of which had also become available online in the form of scanned records from the parish archives from the Azores. Suddenly, my research got easier.

In 2018, I made my first trip to the Azores and Portugal, and before going, I reached out to Nuno Júdice, whose contact information I had kept from that poetry reading decades ago.

To my surprise, Nuno remembered me, and we arranged to meet during my visit to Lisbon in July of that year. We spent a delightful evening together, with Nuno sharing insights into Portuguese poetry, history, and culture. Our connection deepened further when he invited me to write a foreword for David Swartz’s English translation of his novella, The Religious Mantle, and later, he published several of my poems in a literary journal he edited.

In 2020, Nuno graciously provided a blurb for my book Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana, celebrating the work as a poetic exploration of ancestral memory and the experiences of Portuguese emigrants.

Our paths continued to intertwine as the translator Margarida Vale de Gato, whom Nuno had earlier recommended for my poems, agreed to translate my book Dwelling: an ecopoem into Portuguese. Nuno even agreed to help launch the translated edition, Habitar: um ecopoema, in Lisbon in September 2022. In many ways, this felt like coming full circle from our initial encounter at that poetry reading nearly three decades ago.

In a serendipitous twist, Júdice revealed that he had met one of my teachers, the renowned poet Gary Snyder, whom Margarida had also translated, in Madrid in the 1980s. He even shared a draft of a poem he had written about that encounter, further solidifying the interconnectedness of our poetic journeys. When Nuno Júdice passed away last month unexpectedly, I was deeply sad to hear the news from David Swartz; I had just been thinking about Nuno and had planned to write to him. He would have turned 75 years old later this month.

Here is Nuno Júdice’s poem, “Madrid, Anos 80” and my translation from the Portuguese:

MADRID, ANOS 80

Cruzei-me uma vez com Gary Snyder nas Bellas Artes

de Madrid. Eu vinha com livros espanhóis – poesia, e algum

Borges, onde há sempre coisas novas – e cruzei-me com Gary

Snyder, que vinha de ler poemas, mas quando o soube já

a leitura tinha acabado. Também não sei se o iria ouvir: não é

todos os dias que se está em Madrid, com tempo para ir

às livrarias e espreitar museus; e ouvir Gary Snyder pode

não dar jeito ou, pelo menos, obrigar a que se perca alguma coisa

que tão cedo não se voltará a ver. Foi assim que, antes de ir à livraria,

eu tinha passado pelo Caspar David Friedrich, no Prado,

perseguindo montanhas e ruínas da velha Alemanha. Ao sair dali,

com os olhos enevoados pelo mar do Norte, como iria

entrar numa sala para ouvir Gary Snyder? Da próxima vez

que estiver em Madrid, porém, não vai ser assim: e se me cruzar,

nas Bellas Artes, com um poeta que acabe de ler poemas,

mesmo que eu venha da livraria, e tenha passado pelo Prado,

vou arranjar tempo para o ouvir – em homenagem a

Gary Snyder, que não tive tempo

para ouvir.

Nuno Júdice, 26-11-2000

__

MADRID, 80’s

I crossed paths with Gary Snyder once, at Bellas Artes

in Madrid. I was carrying Spanish books – poetry, and some

Borges, where there are always new things – and I bumped into Gary

Snyder, who came to read poems, but by the time I found out

the reading was over. I didn’t know if I would listen to him either: it isn’t

every day that you’re in Madrid, with time to go

to bookstores and look around museums; and listening to Gary Snyder might

not be useful or, at least, make you miss something

that you won’t see again anytime soon. So, before going to the bookstore,

I had passed by Caspar David Friedrich, in the Prado,

chasing mountains and ruins of old Germany. As I left,

with eyes clouded by the North Sea, how was I going to

walk into a room to listen to Gary Snyder? The next time

when I’m in Madrid, however, it won’t be like that: and if you bump into me,

in Bellas Artes, with a poet who has just finished reading poems,

even if I’m coming from the bookstore, and have just passed through the Prado,

I will make time to listen – in honor of

Gary Snyder, who I didn’t have time

to hear.

Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

Last summer, I started a project to translate the Azorean poet Pedro da Silveira’s first book A ilha e o mundo (The Island and the World), which came out in 1952.

I had reviewed the late George Monteiro’s translation of Silveira’s last book, published in a bilingual edition by Tagus Press in the States and simultaneously by Letras Lavadas in the Azores in 2019 as Poems in Absentia & Poems from The Island and the World. In fact, the second half of that title was a misnomer; the book included only a few poems from Silveira’s first book–poems that had previously appeared in a Gávea-Brown anthology from the 1980s and sort of slapped on to the end of the book. (Silveira was born on Flores Island in 1922 and died in Lisbon in 2003.)

What struck me immediately about Silveira’s poetry—in Monteiro’s translation first and then in reading the facing Portuguese—was the depth of its feeling, the simplicity and directness of its language, and the brilliant tapestry woven by strands of memory, naming, and observations of nature. Indeed, all aspects that are found in my own poetry; hence, I felt a certain kinship with Silveira’s work straight away.

And yet, I was equally struck by the dearth of his poetry available in translation. How could such a seemingly important poet be so little represented in English translation? How much richer would the world of poetry–and the world of poetry-in-translation–be with Silveira’s body of work. And how much richer would be our lives in the Azorean diaspora with his sentiments, steadfast observations, and steady poetic hand.

I started with the second poem in the book, “Ilha”; this was likely the first poem I ever read by Silveira in translation, from that old Gávea-Brown anthology previously mentioned.

Here is the entire poem in its original Portuguese:

ILHA Só isto: O céu fechado, uma ganhoa pairando. Mar. E um barco na distância: olhos de fome a adivinhar-lhe, à proa, Califórnias perdidas de abundância.

As I tend to do in my method of translation, I first read the poem straight through and then wrote an impression or literal reading as I understood it:

Just this:

The closed sky, a heron

Hovering. Sea. A boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes guessing, at the prow,

Californias lost of abundance.

A bit clunky and prosaic, and probably unworthy. I prefer to not read another’s translation (if there is one) while translating a poem lest I be influenced by it, so Monteiro’s sat on the shelf.

One thing troubled me, however. The bird. Where did that heron come from? Surely, I remembered it from Monteiro’s version. “Ganhoa,” at first, I thought was a misprint of “ganhou” – who won? – but that made absolutely no sense, so I went with heron. But what was a heron doing in this scene? Were herons even found in the Azores?

Reluctantly, I checked Monteiro’s translation. Sure enough, there it was, “heron.” It struck a dissonant chord with me now. A heron. Really? Again, I wondered whether herons were found in the Azores and turned to the Internet.

Yes, there were at least ten species of heron that have been noted on these islands, including great blues and little egrets, which according to the website whalewatchingazores.com have been sighted, but “not regularly”; the species is classified as an “uncommon vagrant” on the islands. And, most recently, a confirmed sighting of another species, the yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) was described in a scientific paper by João Pedro Barreiros. Most likely, however, this one was blown east by a strong, errant wind from the west. Several herons were known to stop-over on their migratory path from Africa to northern climes and back.

Still, heron didn’t seem correct, to me, given the scene described. The use of Mar all alone. And the boat seemed to imply open waters rather than shoreline.

Herons are marsh-dwelling, shoreline species for the most part, so I was perplexed why they might be hovering “at Sea” or the “open ocean,” as I envisioned it. Were they blown off-course and out of their range? That would surely change the nature of this poem, which I assumed was about emigration or the emigrant returned or the desire to emigrate but also remain tied to the island. If it was not a heron, what was it then? What else might “hover” over the open ocean?

I typed “ganhoa” into Google. The almighty, all-seeing Google asked if I meant “ganhos” earnings; no, I did not. This was not a poem set in the halls of finance or a casino in Monaco. So, I clicked on “search instead for ganhoa” and up came a page from Priberam dicionário. I had my bird! The yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis atlantis)…surely this bird would hover over the prow or bow of the boat, and even the stern, looking for a handout. A ganhoa recupera os seus ganhos. (The gull recovers its winnings.)

Here is my version of Pedro da Silveira’s “Island”:

Just this:

The closed sky, a yellow-legged gull

hovering. Open ocean. And a boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes, at the bow, divining,

lost Californias of plenty.

(Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

____

(This text was adapted from a paper delivered at the Colóquio celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pedro da Silveira, “Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedro cultural,” at the University of the Azores in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, in September 2022.)

Speaking of the Azores: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

My friend and colleague Leonor Sampaio da Silva published her first collection of poems last summer, Quase um Carimbo (Companhia das Ilhas, 2022).

Born on the island of São Miguel, Azores, Leonor holds a master’s degree in Anglo-Portuguese Studies from the Universidade Novo de Lisboa and a PhD in Anglo-American Studies from the University of the Azores, where she has taught since 1991.

Having published a number of academic papers and contributions to various books, anthologies, and literary magazines, Leonor made her literary debut with a book of short stories, Mau Tempo e Má Sorte – contos pouco exemplares, which received the Daniel de Sá Humanities Prize in 2014. She is also the author of ABN da Pessoa com Universo ao Fundo (2017) and, with Carlos Carvalho, Pouca Terra – Fotografia e Literatura (2019).

“My idea for [this] book was to talk about the experience of isolation caused by the pandemic,” Leonor explained to me. “In which we lost contact with others and forced ourselves to face situations such as the vulnerability of life, how to make sense of each day, how to live with routine.”

Some of the poems read like diary entries, the poetic voice spoken by characters representing, as Leonor notes, “the others that exist within and outside of oneself.”

“Carimbo,” it may be useful to note, means “stamp,” the kind used to mark or authenticate official or private papers. Another meaning of the word, however, is “timestamp” (although usually written as “carimbo de data/hora.”) and, in this collection, each poem is marked by a timestamp: morning, afternoon, or night, as well as an action–I wake up, I sit down, I get up–as if to indicate stage direction.

It’s as if the characters in the poems are actors in their own play, marking their time, the pandemic imbuing even the most mundane tasks with the aspects of a theatrical production.

The book title translates as “Almost a Stamp,” which leads the reader to a question: if it is “almost,” what is it? An approximation? What is reality? The questions are heightened by the ending of the book where the theatrical stage suddenly becomes cinematic, play becomes film, language shifts in tone, the curtain falls, a wind picks up, a torrential rain pours down, and fallen leaves return to their trees. The speaker remains lonely. The book ends with one last action: “Adormeço” (I fall asleep).

“Poetry,” Leonor argues, “is a way of putting us in touch with each other and exploring new languages.” She carries this thread throughout the collection, whether using “the more intimate language of the diary/newspaper” or “the more social language of the theater,” demonstrating that “everything happens as if on a stage” and shielding us from loneliness and death.

Quase um Carimbo is an impressive debut poetry collection and I hope to translate more of it in the future.

Here are two poems by Leonor Sampaio da Silva in the original Portuguese and my translations into English:

manhã

acordo

uma personagem pragueja baixinho

pela noite mal dormida

o que farei se um Comboio transformar

a geografia deste lugar?

pensar no improvável tem sido

passatempo habitual

quase uma Obsessão

preocupa-me em demasia

a falta de uma Estação

—

morning

I wake up

a character curses softly

over the sleepless night

what will I do if a train transforms

the geography of this place?

thinking about the improbable has been

a regular hobby

almost an obsession

it worries me too much

the lack of a station

________

manhã

acordo

deve estar um dia quente a avaliar pela

temperatura do quarto

o corpo, o que é um corpo?

uma madeixa cortada

vivendo por um fio

enquanto aguarda reunir-se

à cabeça que dela se esqueceu

uma madeixa que se deixa

varrer

alisar

torcer em caracol

alourar ao sol

o sol, o que é o sol?

um corpo

—

morning

I wake up

it must be a hot day judging by

the temperature of the room

a body, what is a body?

a severed lock

living by a thread

while waiting to be reunited

with the head that has forgotten it

a lock that lets itself

sweep

smooth

twists into a curl

glistening in the sun

the sun, what is the sun?

a body

–Leonor Sampaio da Silva, from Quase um Carimbo

(translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

___

Speaking of the island of São Miguel: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

Photo by Ana Cristina Gil, University of the Azores.

My apologies for not being on top of my game with regards to National Poetry Month Mailings this year. Samantha and I just returned from an emotional trip to our beloved island of São Miguel, in the Azores, after two years away.

It was emotion-filled not only because the pandemic kept us way for two years—we had tried to go back as recently as December, but Omicron dissuaded us—but because in the interim years we had determined that we want to divide our time between there and our new home in the Berkshires and this trip solidified and confirmed that plan.

On top of that, we held a ceremony to place a plaque at the Praça do Emigrante (Emigrant Square) honoring the memory and sacrifice of my two great-grandparents who emigrated from the island in 1906. Joining us were cousins from my family there, the Casquilho family, along with the director and staff from the Associação dos Emigrantes Açorianos.

It was a windy afternoon, and the waves were crashing against the rocky shore along the north coast of the island, as if the spirit of my great-grandparents were making their presence known.

All this to say that I’m behind in my weekly mailings and I apologize. This week, I’m going to share post one of my translations of the great Azorean poet Vitorino Nemésio, “Ship,” which I hope you will enjoy. It originally appeared in Gávea-Brown Journal and was reprinted in my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. Here it is in the original Portuguese and in my translation:

Navio

Tenho a carne dorida

Do pousar de umas aves

Que não sei de onde são:

Só sei que gostam de vida

Picada em meu coração.

Quando vêm, vêm suaves;

Partindo, tão gordas vão!

Como eu gosto de estar

Aqui na minha janela

A dar miolos às aves!

Ponho-me a olhar para o mar:

—Olha-me um navio sem rumo!

E, de vê-lo, dá-lho a vela,

Ou sejam meus cílios tristes:

A ave e a nave, em resumo,

Aqui, na minha janela.

—Vitorino Nemésio, Nem Toda A Noite A Vida

___

Ship

My flesh is sore

from the landing of some birds

I don’t know where they’re from.

I only know that they, like life,

sting in my heart.

When they come, they come softly;

leaving, they go so heavy!

How I like to be

here at my window

giving my mind over to the birds!

I’m looking at the sea:

look at that aimless ship!

And, seeing it, give it a lamp[i],

or my sad eyelashes:

the bird and the ship, in a nutshell,

here, at my window.

—translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

[i] For “vela,” I like “lamp” here, rather than “candle” or “sail,” because it echoes the idea of lighting a lamp to draw in a weary traveler—although I think “salute” or “sign” might also work, although not technically accurate. Also “lamp” hearkens back to Nemésio’s stated desire, expressed in his Corsário das Ilhas, which I’ve been translating for Tagus Press, of wanting to be a lighthouse keeper.

WINE-DARK SEA BOOK LAUNCH & READING

March 2, 2022

In conversation with Kathryn Miles

On #pubday eve, Kathryn Miles and I got together to chat about my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. We had a wide-ranging conversation about the book, specific poems, finding love at middle age, the idea of home, and the Azores — and I even read a poem in Portuguese.

Have a look here:

The book came out March 1st and is available through the links on my website: scottedwardanderson.com/wine-dark-sea

National Poetry Month 2021, Bonus Week: My translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s “A Árvore do Silêncio”

May 2, 2021

For my bonus post this year, wrapping up this Poetry Month featuring poets of the Azores and its Diaspora, I want to share one of my translations of the great 20th Century Azorean poet Vitorino Nemésio. (This translation appears in the current issue of Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, along with four others.)

Photo by Manuel de Sousa, Creative Commons License

A poet, essayist, and public intellectual, Nemésio was born on Terceira Island in 1901 and is best known for his novel Mau tempo no canal (1945), which was translated into English by Francisco Cota Fagundes and published as Stormy Isles: An Azorean Tale.

In 1932, the quincentennial year of Gonçalo Velho Cabral’s “discovery” of the Azores, Nemésio coined the term “açorianidade,” which he would explore in two important essays, and which would become the subject of much debate over the years. There are those who see the term as somewhat limiting: describing as it does a specific, fixed set of qualities of the island condition—insularity, for example—that belies a greater dynamism in the spirit of the islanders.

Nevertheless, I think its usefulness as a term is somewhat expanded when we look at what Nemésio himself said about it, reflecting the entirety of his term rather than one dimension of it. Instead of limiting it as a descriptor to what it’s like to be born on the islands, Nemésio asserted that it was appropriate, too, for those who emigrated from the islands, as well as those who later returned. (And, by extension, as I said in a recent interview, I like to think he intended it to continue through or beyond the generations.)

The term, wrote Antonio Machado Pires in his essay, “The Azorean Man and Azoreanity,” “not only expresses the quality and soul of being Azorean, inside or outside (mainly outside?) of the Azores, but the set of constraints of archipelagic living: its geography (which ‘is worth as much as history’), its volcanism, its economic limitations, but also its own capacity as a traditional ‘economy’ of subsistence, its manifestations of culture and popular religiosity, their idiosyncrasy, their speaking, everything that contributes to verify identity.”

As a “warm-up exercise” for translating Nemésio’s travel diary, Corsário das Ilhas (1956), for which I am currently under contract with Tagus Press of UMass Dartmouth (with financial support from Brown University), I started with some of his poems. And I hope to continue with more, because Nemésio is worthy of a larger audience here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief tour of some of the poetry of the Azores and its Diaspora.

Here is Vitorino Nemésio’s “A Árvore do Silêncio” and my translation, “The Tree of Silence”:

A ÁRVORE DO SILÊNCIO

Se a nossa voz crescesse, onde era a árvore?

Em que pontas, a corola do silêncio?

Coração já cansado, és a raiz:

Uma ave te passe a outro país.

Coisas de terra são palavra.

Semeia o que calou.

Não faz sentido quem lavra

Se o não colhe do que amou.

Assim, sílaba e folha, porque não

Num só ramo levá-las

com a graça e o redondo de uma mão?

(Tu não te calas? Tu não te calas?!)

—Vitorino Nemésio de Canto de Véspera (1966)

_____________

THE TREE OF SILENCE

If our voice grew, where was the tree?

To what ends, the corolla of silence?

Heart already tired, you are the root:

a bird passes you en route to another country.

Earthly things are word.

Sow what is silent.

It doesn’t matter who plows,

if you don’t reap what you loved.

So, why not take them,

syllable and leaf, in a single bunch

with the graceful roundness of one hand?

(Don’t you keep quiet? Don’t you keep quiet?!)

—translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

from Gávea-Brown—A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, vol. 43. Brown University, 2021

National Poetry Month 2021, Week Four: Adelaide Freitas’s “In the Bulge of Your Body”

April 30, 2021

Continuing to explore the poets and poetry of the Azores and its Diaspora, this week I’m featuring a poem by the late Adelaide Freitas, a wonderful Azorean poet, novelist, and essayist deserving of more attention.

Freitas was born 20 April 1949 in Achadinha, on the northeastern coast of São Miguel Island. She attended school in Ponta Delgada before moving with her family to the United States, where she attended New Bedford High School in Massachusetts. In 1972, she graduated with a BA in Portuguese from the Southeastern Massachusetts University (now UMass Dartmouth) and went on to earn a master’s degree in Comparative Literature from the City University of New York and a PhD in American Literature from the University of Azores. She lived in Ponta Delgada with her husband, Vamberto Freitas, and was a professor of American Literature and Culture at the University of the Azores.

In 2018, Adelaide Freitas was honored by the Legislative Assembly of the Autonomous Region of the Azores with the Insígnia Autonómica de Reconhecimento (Commendation of Recognition), just a few weeks before she passed away after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.

“Adelaide Freitas had gone silent years ago through the devastation of illness,” wrote one of her translators, Emanuel Melo, on his blog. “Her husband, Vamberto Freitas, himself a man of letters and important literary critic in the Portuguese diaspora, with enduring love and faithfulness kept her by his side, even writing about her, but above all loving her with steadfastness. In one of his blog posts he wrote how in the middle of a sleepless night, with her resting in the next room, he would take her books from the shelf and read her words to himself when he could no longer her the voice of his beloved wife.”

Her novel, Smiling in the Darkness, is an intimate portrait of what life was like on the Azores during the latter half of the 20th Century, and follows a young woman who struggles with the absence of her emigrant parents—who left her behind when they went to America—and her desire to explore the world beyond her island home. It was recently published in a translation by Katherine Baker, Emanuel Melo, and others. You can order a copy (and you should) from Tagus Press here: Smiling in the Darkness.

Here is her poem, “No bojo do teu corpo” in its original Portuguese and my English translation:

“No bojo do teu corpo”

No bojo do teu copo

olho translúcido o teu corpo

Vibra a alegria da tua emoção

e em mim se dilui a sua gota

Ballet agita o copo

treme a boca da garrafa

A mão abafa o vidro morno

cala-se enterrada a ternura dos lábios

A folha verde voa etérea

pousa no líquido desfeito

Dela nasce uma flor

e o mundo nela se espelha

branca a luz se intersecta

refrecta o whisky beijado

Guardanapo assim molhado

refresca a tua fronte

Gentil ela se inclina

no Outro se confunde

No tchim-tchim da efusão

treme bojo do teu corpo

—

“In the bulge of your body”

In the bulge of your glass

I see your translucent body

Vibrating with the joy of your emotion

and your drop dissolves in me

Ballet stirs the glass

the mouth of the bottle is trembling

The hand stifles the tepid glass

the tenderness of the lips is buried, remains silent

The green leaf flies ethereal

lands in the dissolved liquid

From it a flower is born

and the world is mirrored in it

white light intersects

refracting the whisky kiss

Such a wet napkin

refreshing your brow

Gently she leans

into the Other, gets confused

In the Tchim-tchim![1] of effusion

the bulge of your body trembles

—Adelaide Freitas (translated by Scott Edward Anderson)

[1] Tchim-tchim! is an expression like Cheers! An onomatopoeic phrase that connotes the clinking of glasses. I decided not to translate it here, although I could have gone with “cling-cling!” or something similar.