I’d almost forgotten to write my post for Week Four of National Poetry Month when I realized it was the last night of April and poetry month would soon be over for another year. I had no idea what poem or poet to feature although, having recently returned from Fall River, MA, where I had been part of the first Poesia Festival there, I thought it might be one of the Portuguese poets featured at the event: Camões, Silveira, Amaral, Pessoa, or Medeiros. (I’d already featured Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen the previous week.)

“It can wait until tomorrow,” I told myself, turning on Game 5 of the Boston Bruins Stanley Cup playoff game against the Toronto Maple Leafs, which my team lost in overtime.

This morning, I woke to the news that Paul Auster had died at 77 years old after a long battle with lung cancer. I have a long, tenuous, and tangential relationship with Paul Auster dating back to the late 1980s, when I was part of a writing group called the “Decompositionalists” and worked in publishing. I texted one of the other members of that writing group who had been a big fan of the author of City of Glass. “I still treasure The New York Trilogy,” she texted back. “Something of a shock to learn of his passing, though every time I saw him he was smoking.”

When I was a young editor at Viking Penguin, Auster, in all his swarthy, 38-year-old handsomeness used to come into the office to meet with his editor. All the young women—or, rather, ALL the women would swoon, and many of the men, too! “He is smoking hot,” a colleague at the time explained to me when I asked what the attraction was. “There’s nothing like a smoking hot intellectual to make an editorial department swoon.”

While Auster was best known as a highly acclaimed novelist and writer of prose fiction, memoirs, and essays, he started as a poet and translator, living in Paris after graduating from Columbia in 1969. It wasn’t lost on me that Auster, who had partaken in the student protests at Columbia University in 1968, died the day the NYPD sent in its surge troops to evict students from Hamilton Hall, a building they were occupying as part of a pro-Palestinian protest.

The earlier protest, which police also cracked down upon on April 30th fifty-six years ago, ended in violence that resulted in more than 700 arrests and 148 reports of injuries as “officers trampled protesters, hit them with night sticks, punched and kicked them down stairs,” according to The New York Times.

While Auster’s poetry has been overshadowed by his prose, he published several volumes of poetry over his career, including Unearth (1974), Wall Writing (1976), and Facing the Music (1980). Two volumes of selected poems, Disappearances (1988) and Ground Work (1990) along with a volume of Collected Poems (2007), were also published.

His poetry tends to have an experimental, avant-garde style influenced by French writers and surrealists, wherein, as in much of his fiction, he explores themes of chance, games, language play, intertextuality, and the role of the author. While respected, his poetry has received less mainstream attention and acclaim compared to his novels like 4321 (2017), The New York Trilogy (1987), The Book of Illusions (2002), and The Brooklyn Follies (2005).

Auster rather famously wrote with a fountain pen. “If I could write directly on a computer or typewriter, I would do it. But keyboards have always intimidated me,” he said in an interview with The Paris Review. “A pen is a much more primitive instrument. You feel that the words are coming out of your body, and then you dig the words into the page. Writing has always had that tactile quality for me. It’s a physical experience.”

Auster explores the relationship between the body and language in his poem, “White Nights,” with a characteristic hint of surrealism. RIP Paul Auster (1947-2024). Here is Paul Auster’s poem:

WHITE NIGHTS

No one here,

and the body says: whatever is said

is not to be said. But no one

is a body as well, and what the body says

is heard by no one

but you.

Snowfall and night. The repetition

of a murder

among the trees. The pen

moves across the earth: it no longer knows

what will happen, and the hand that holds it

has disappeared.

Nevertheless, it writes.

It writes: in the beginning,

among the trees, a body came walking

from the night. It writes:

the body’s whiteness

is the color of earth. It is earth,

and the earth writes: everything

is the color of silence.

I am no longer here. I have never said

what you say

I have said. And yet, the body is a place

where nothing dies. And each night,

from the silence of the trees, you know

that my voice

comes walking toward you.

–Paul Auster, from Disappearances: Selected Poems, Overlook Press, 1988

National Poetry Month 2019, Week Three: Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s “Descobrimento”

April 22, 2024

This Thursday marks the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, whereby the people of Portugal overthrew the dictatorship under which they had lived for forty-eight years. I have previously shared my translation of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s poem of the revolution, “25 de Abril” (“25th of April”). Sophia was born in Porto in 1919, she died in 2004 at the age of 84 and is now buried in the National Pantheon in Lisbon, an honor recognizing her as one of Portugal’s greatest poets.

Her work often explored themes of nature, particularly the power and mystery of the sea. Indeed, she can be considered a poet of the sea. One poem that encapsulates her maritime inspiration is “Descobrimento” (“Discovery”). In “Discovery,” Andresen paints a vivid, almost surreal portrait of the ocean through metaphor and visceral imagery. She writes of “An ocean of green muscles/ An idol with as many arms as an octopus/ Incorruptible chaos that erupts/ And orderly turmoil…” [my translation]. This strange yet mesmerizing depiction captures the paradoxical nature of the sea — its turbulent, ungovernable force coexisting with an inherent rhythm and pattern.

The sea represented many things for Andresen beyond its literal presence. As a dedicated Hellenist, she found inspiration in ancient Greek mythology and often blurred the lines between the Atlantic Ocean of her Portuguese homeland and the Mediterranean. The sea became a symbol of renewal, eternity, and the mysteries of life and death.

Her reverence for the ocean likely stemmed from her childhood spent along the coast in Porto, watching the ebb and flow of the tides. The poem evokes her early, formative experiences at Praia de Granja, a beach south of Porto that shaped her poetic vision.

In “Discovery,” Andresen seems to be urging the reader to explore the depths of the ocean and surrender to its “incorruptible chaos.” The sea is both menacing with its crashing waves and comforting in its ceaseless cadence. By wading into those waters, perhaps we can access greater truths about ourselves and the world around us.

With her luminous language and profound naturalism, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen invites the reader to discover the ocean anew through her transcendent poetry. “Discovery” reminds us that the seas contain not just thrilling adventures and discoveries, but insights into the very essence of our existence.

Here is my translation of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s “Descobrimento”:

Discovery

An ocean of green muscles

An idol with as many arms as an octopus

Incorruptible chaos that erupts

And orderly turmoil

Dancer twisted up

Around the outstretched ships

We cross rows of horses

Who shake their manes at the trade winds

The sea suddenly became too young and too old

To show the beaches

And a people

Of newly created men still clay-colored

Still naked, still dazzled

—

Here is the poem in its original Portuguese:

Descobrimento

Um oceano de músculos verdes

Um ídolo de muitos braços como um polvo

Caos incorruptível que irrompe

E tumulto ordenado

Bailarino contorcido

Em redor dos navios esticados

Atravessamos fileiras de cavalos

Que sacudiam as crinas nos alísios

O mar tornou-se de repente muito novo e muito antigo

Para mostrar as praias

E um povo

De homens recém-criados ainda cor de barro

Ainda nus ainda deslumbrados

–Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen

From Obra Poética III, published by Caminho, Lisboa

To hear Sophia read her poems in 1985: https://www.loc.gov/item/93842563/

My translations of Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, along with several other Portuguese poets, appear in my book Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations (Shanti Arts, 2022), available through this link or wherever you buy books.

Poet Daisy Fried recently lamented how “very little of [poetry published in the past year] has any sense of fun.” This reminded me of Thomas Lux, one of my favorite poets whose works were often sardonically funny yet possessed a deep poignancy and empathy. Lux was a master at blending humor and pathos to capture the absurdities of the human condition.

Lux played minor subjects in a major key. He was a keen observer, and like a bower bird, he collected quirky details of everyday life into a wide-ranging body of work. The music critic Ted Burke once called him “the Laureate of Unintended Results,” as Lux’s poems often start with a simple observation that spirals into unexpected revelations. He could be tender and funny in the same piece, as in “Upon Seeing an Ultrasound of an Unborn Child,” “I Love You Sweatheart,” or “Tarantulas on the Lifebuoy.”

In 1998, Lux selected my work for the Larry Aldrich Emerging Poets Award. Having grown up on a Massachusetts farm, he seemed drawn to the rural, straightforward voice in my poems about country life. I was fortunate his sensibilities resonated with my writing.

A generous man and masterful live performer, Lux taught for decades at Georgia Tech, holding the Bourne Chair in Poetry. His poem “Refrigerator, 1957” illuminates the juxtaposition of delight and melancholy he captured so well. The opening lines present an ordinary relic of mid-20th century American kitchens — “the jar of maraschino cherries/on the third shelf…” But Lux transforms this mundane image into a profound meditation on the passing of time and the contradictions of memory:

“…I’m eight, and time

is both endless and negligible…”

In reflecting on this ubiquitous 1950s object, the poem evokes the depth of humor, nostalgia, and loss that Lux could unearth from the artifacts of everyday life. His poetry revealed the extraordinary in the ordinary in a voice that, as Daisy Fried yearned for, is undeniably fun.

Here is Tom Lux’s poem:

Refrigerator, 1957

More like a vault: you pull the handle out

and on the shelves not a lot,

and what there is (a boiled potato

in a bag, a chicken carcass

under foil) looking dispirited,

drained, mugged. This is not

a place to go in hope or hunger.

But, just to the right of the middle

of the middle door shelf, on fire, a lit-from-within red,

heart-red, sexual-red, wet neon-red,

shining red in their liquid, exotic,

aloof, slumming

in such company: a jar

of maraschino cherries. Three-quarters

full, fiery globes, like strippers

at a church social. Maraschino cherries, “maraschino”

the only foreign word I knew. Not once

did I see these cherries employed: not

in a drink, nor on top

of a glob of ice cream,

or just pop one in your mouth. Not once.

The same jar there through an entire

childhood of dull dinners—bald meat,

pocked peas, and, see above,

boiled potatoes. Maybe

they came over from the old country,

family heirlooms, or were status symbols

bought with a piece of the first paycheck

from a sweatshop,

which beat the pig farm in Bohemia,

handed down from my grandparents

to my parents

to be someday mine,

then my child’s?

They were beautiful

and if I never ate one

it was because I knew it might be missed

or because I knew it would not be replaced

and because you do not eat

that which rips your heart with joy.

–Thomas Lux

(This poem originally appeared in the New Yorker in 1997, and subsequently in Tom’s New & Selected Poems, published the same year. Here is a recording of Tom reading his poem at the Robert Creeley Awards ceremony in March of 2012: “Refrigerator, 1957”.)

In December 1994, I attended a poetry reading at Poets House in New York by two Portuguese poets, Nuno Júdice and Pedro Tamen, along with the translator, Richard Zenith. Little did I know that this event would have an impact on the profound journey into my ancestral roots in Portugal and the Azores.

After my Portuguese grandfather passed away in September 1993, I was at a loss to uncover our family’s history, which he had been reluctant to share. Hearing Júdice and Tamen read their poems in Portuguese the following December was a revelation of sorts—here were real, live Portuguese poets speaking the language of my ancestors.

The dearth of first-hand accounts and available source materials kept me from learning my family’s Portuguese Azorean history for many years and, frankly, life got in the way of digging deeper. When my father died in 2016, I realized that all my family’s histories were available to me, except one part—the Portuguese. By then, Ancestry.com had made many research materials available online for the first time, and a group of Azorean Genealogists gathered on a listserv to share information, leads, and help translate documents from the Azores, much of which had also become available online in the form of scanned records from the parish archives from the Azores. Suddenly, my research got easier.

In 2018, I made my first trip to the Azores and Portugal, and before going, I reached out to Nuno Júdice, whose contact information I had kept from that poetry reading decades ago.

To my surprise, Nuno remembered me, and we arranged to meet during my visit to Lisbon in July of that year. We spent a delightful evening together, with Nuno sharing insights into Portuguese poetry, history, and culture. Our connection deepened further when he invited me to write a foreword for David Swartz’s English translation of his novella, The Religious Mantle, and later, he published several of my poems in a literary journal he edited.

In 2020, Nuno graciously provided a blurb for my book Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana, celebrating the work as a poetic exploration of ancestral memory and the experiences of Portuguese emigrants.

Our paths continued to intertwine as the translator Margarida Vale de Gato, whom Nuno had earlier recommended for my poems, agreed to translate my book Dwelling: an ecopoem into Portuguese. Nuno even agreed to help launch the translated edition, Habitar: um ecopoema, in Lisbon in September 2022. In many ways, this felt like coming full circle from our initial encounter at that poetry reading nearly three decades ago.

In a serendipitous twist, Júdice revealed that he had met one of my teachers, the renowned poet Gary Snyder, whom Margarida had also translated, in Madrid in the 1980s. He even shared a draft of a poem he had written about that encounter, further solidifying the interconnectedness of our poetic journeys. When Nuno Júdice passed away last month unexpectedly, I was deeply sad to hear the news from David Swartz; I had just been thinking about Nuno and had planned to write to him. He would have turned 75 years old later this month.

Here is Nuno Júdice’s poem, “Madrid, Anos 80” and my translation from the Portuguese:

MADRID, ANOS 80

Cruzei-me uma vez com Gary Snyder nas Bellas Artes

de Madrid. Eu vinha com livros espanhóis – poesia, e algum

Borges, onde há sempre coisas novas – e cruzei-me com Gary

Snyder, que vinha de ler poemas, mas quando o soube já

a leitura tinha acabado. Também não sei se o iria ouvir: não é

todos os dias que se está em Madrid, com tempo para ir

às livrarias e espreitar museus; e ouvir Gary Snyder pode

não dar jeito ou, pelo menos, obrigar a que se perca alguma coisa

que tão cedo não se voltará a ver. Foi assim que, antes de ir à livraria,

eu tinha passado pelo Caspar David Friedrich, no Prado,

perseguindo montanhas e ruínas da velha Alemanha. Ao sair dali,

com os olhos enevoados pelo mar do Norte, como iria

entrar numa sala para ouvir Gary Snyder? Da próxima vez

que estiver em Madrid, porém, não vai ser assim: e se me cruzar,

nas Bellas Artes, com um poeta que acabe de ler poemas,

mesmo que eu venha da livraria, e tenha passado pelo Prado,

vou arranjar tempo para o ouvir – em homenagem a

Gary Snyder, que não tive tempo

para ouvir.

Nuno Júdice, 26-11-2000

__

MADRID, 80’s

I crossed paths with Gary Snyder once, at Bellas Artes

in Madrid. I was carrying Spanish books – poetry, and some

Borges, where there are always new things – and I bumped into Gary

Snyder, who came to read poems, but by the time I found out

the reading was over. I didn’t know if I would listen to him either: it isn’t

every day that you’re in Madrid, with time to go

to bookstores and look around museums; and listening to Gary Snyder might

not be useful or, at least, make you miss something

that you won’t see again anytime soon. So, before going to the bookstore,

I had passed by Caspar David Friedrich, in the Prado,

chasing mountains and ruins of old Germany. As I left,

with eyes clouded by the North Sea, how was I going to

walk into a room to listen to Gary Snyder? The next time

when I’m in Madrid, however, it won’t be like that: and if you bump into me,

in Bellas Artes, with a poet who has just finished reading poems,

even if I’m coming from the bookstore, and have just passed through the Prado,

I will make time to listen – in honor of

Gary Snyder, who I didn’t have time

to hear.

Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

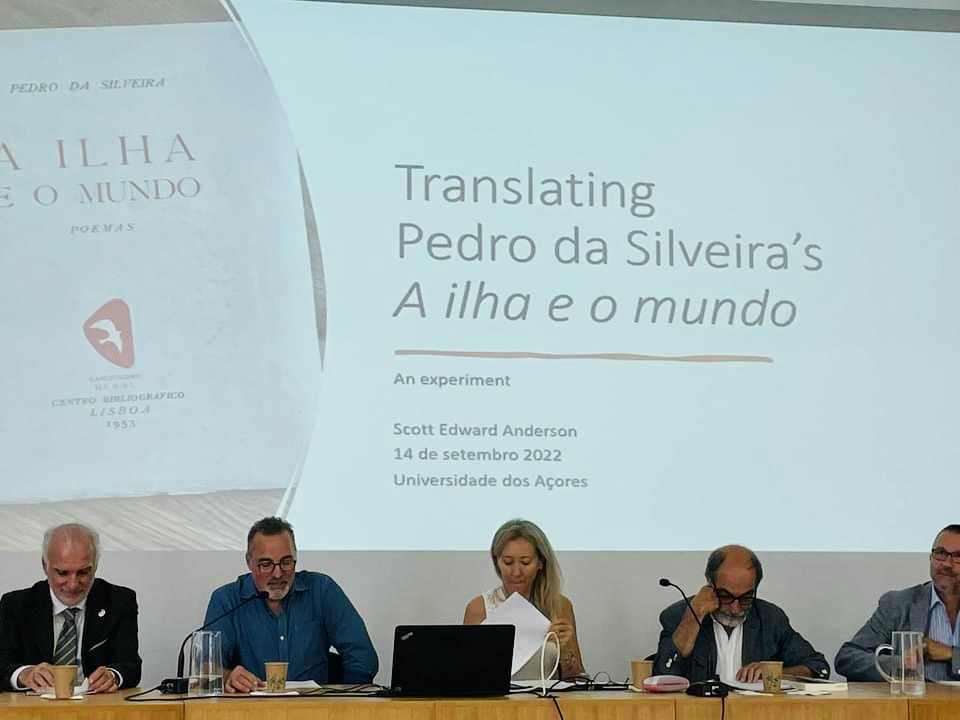

Last summer, I started a project to translate the Azorean poet Pedro da Silveira’s first book A ilha e o mundo (The Island and the World), which came out in 1952.

I had reviewed the late George Monteiro’s translation of Silveira’s last book, published in a bilingual edition by Tagus Press in the States and simultaneously by Letras Lavadas in the Azores in 2019 as Poems in Absentia & Poems from The Island and the World. In fact, the second half of that title was a misnomer; the book included only a few poems from Silveira’s first book–poems that had previously appeared in a Gávea-Brown anthology from the 1980s and sort of slapped on to the end of the book. (Silveira was born on Flores Island in 1922 and died in Lisbon in 2003.)

What struck me immediately about Silveira’s poetry—in Monteiro’s translation first and then in reading the facing Portuguese—was the depth of its feeling, the simplicity and directness of its language, and the brilliant tapestry woven by strands of memory, naming, and observations of nature. Indeed, all aspects that are found in my own poetry; hence, I felt a certain kinship with Silveira’s work straight away.

And yet, I was equally struck by the dearth of his poetry available in translation. How could such a seemingly important poet be so little represented in English translation? How much richer would the world of poetry–and the world of poetry-in-translation–be with Silveira’s body of work. And how much richer would be our lives in the Azorean diaspora with his sentiments, steadfast observations, and steady poetic hand.

I started with the second poem in the book, “Ilha”; this was likely the first poem I ever read by Silveira in translation, from that old Gávea-Brown anthology previously mentioned.

Here is the entire poem in its original Portuguese:

ILHA Só isto: O céu fechado, uma ganhoa pairando. Mar. E um barco na distância: olhos de fome a adivinhar-lhe, à proa, Califórnias perdidas de abundância.

As I tend to do in my method of translation, I first read the poem straight through and then wrote an impression or literal reading as I understood it:

Just this:

The closed sky, a heron

Hovering. Sea. A boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes guessing, at the prow,

Californias lost of abundance.

A bit clunky and prosaic, and probably unworthy. I prefer to not read another’s translation (if there is one) while translating a poem lest I be influenced by it, so Monteiro’s sat on the shelf.

One thing troubled me, however. The bird. Where did that heron come from? Surely, I remembered it from Monteiro’s version. “Ganhoa,” at first, I thought was a misprint of “ganhou” – who won? – but that made absolutely no sense, so I went with heron. But what was a heron doing in this scene? Were herons even found in the Azores?

Reluctantly, I checked Monteiro’s translation. Sure enough, there it was, “heron.” It struck a dissonant chord with me now. A heron. Really? Again, I wondered whether herons were found in the Azores and turned to the Internet.

Yes, there were at least ten species of heron that have been noted on these islands, including great blues and little egrets, which according to the website whalewatchingazores.com have been sighted, but “not regularly”; the species is classified as an “uncommon vagrant” on the islands. And, most recently, a confirmed sighting of another species, the yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) was described in a scientific paper by João Pedro Barreiros. Most likely, however, this one was blown east by a strong, errant wind from the west. Several herons were known to stop-over on their migratory path from Africa to northern climes and back.

Still, heron didn’t seem correct, to me, given the scene described. The use of Mar all alone. And the boat seemed to imply open waters rather than shoreline.

Herons are marsh-dwelling, shoreline species for the most part, so I was perplexed why they might be hovering “at Sea” or the “open ocean,” as I envisioned it. Were they blown off-course and out of their range? That would surely change the nature of this poem, which I assumed was about emigration or the emigrant returned or the desire to emigrate but also remain tied to the island. If it was not a heron, what was it then? What else might “hover” over the open ocean?

I typed “ganhoa” into Google. The almighty, all-seeing Google asked if I meant “ganhos” earnings; no, I did not. This was not a poem set in the halls of finance or a casino in Monaco. So, I clicked on “search instead for ganhoa” and up came a page from Priberam dicionário. I had my bird! The yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis atlantis)…surely this bird would hover over the prow or bow of the boat, and even the stern, looking for a handout. A ganhoa recupera os seus ganhos. (The gull recovers its winnings.)

Here is my version of Pedro da Silveira’s “Island”:

Just this:

The closed sky, a yellow-legged gull

hovering. Open ocean. And a boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes, at the bow, divining,

lost Californias of plenty.

(Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

____

(This text was adapted from a paper delivered at the Colóquio celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pedro da Silveira, “Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedro cultural,” at the University of the Azores in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, in September 2022.)

Speaking of the Azores: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

National Poetry Month 2023, Week Four: Hannah Linden’s “My daughter says the ghosts were busy last night”

April 24, 2023

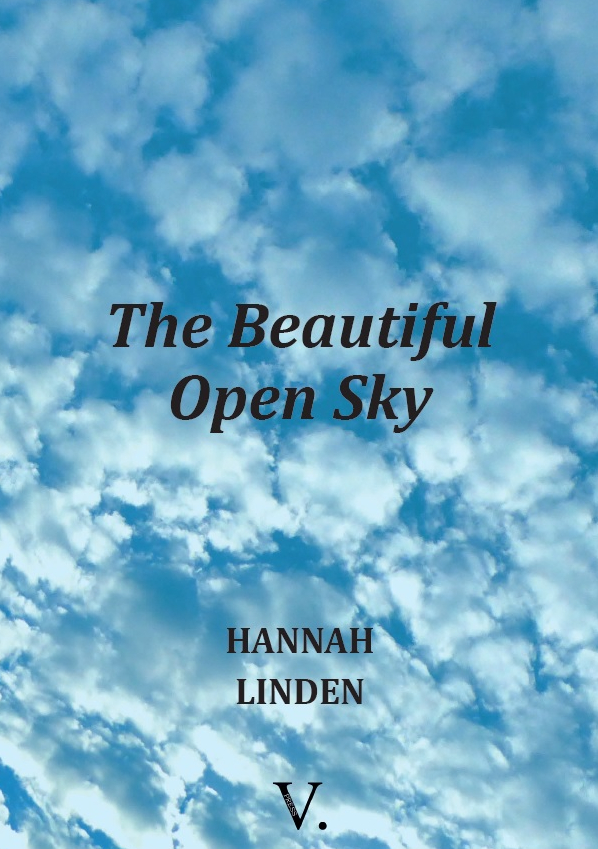

I first read Hannah Linden’s poetry in 2014, when we were both part of Jo Bell’s “52” group of writers–a number of us committing to write a poem each week for the entire year. We shared our work-in-progress in response to the prompts Jo supplied us with each week in a private Facebook group. Hannah’s writing stood out from the group and I was delighted when she announced last year that her first pamphlet, The Beautiful Open Sky, was coming out in the Fall. (A pamphlet is what the Brits call a small selection of poems; what we in the States might call a chapbook.)

Hannah is from a working class background, as she puts it, born in a “cotton mill town slum” in northern England. Poetry “didn’t seem like something one of us could write or think of as ‘ours,’” she said in an interview. Later, she “started writing poems on paper bags,” while working the register at a supermarket. Her co-workers “told people to come to their till instead because ‘can’t you see the poet is writing!’”

Some early encouragement from a teacher led her to enter some poems into a prize competition, which she won. She went to university–the first in her family to do so–but “felt in awe of all writers, out of my depth and that I was kidding myself to think I could be ‘one of them’.” She gave up writing poetry until she was in her early thirties, having moved from the North to Devon, where she took some poetry classes, but got discouraged by a teacher there, and didn’t read or write poetry for fourteen years while raising her children. A random meeting with Mike Sims of the Poetry Society led to her sharing poems with him and he encouraged her to write more. Then she joined Simon Williams’ Poem-a-Day forum and “52.”

In the interview, Hannah explained that in these poems she “was interested in the way ‘mother’ is both a role and a relationship.” The Beautiful Open Sky opens with a series of poems exploring the damage inflicted by a narcissistic mother. The voice in the poems shifts from the mother “saying what she thinks her children may be feeling and then she lets them start to speak for themselves whilst navigating the role of a single parent.” Finally, “as her children mature, the mother starts to relate to them more as independent people and, in the last poem, the adult daughter herself is speaking in the poem’s title as the mother comes to terms with letting go.”

As Hannah says in the interview, “the ‘beautiful open sky’ is a way of trying to see the world when a series of situations are weighing you down, oppressing or terrifying you.”

My daughter says the ghosts were busy last night

I’m getting old. I don’t hear the creaks

even on the nights she wakes me, unable

to settle into the cooling house. It could be

owls, I say. They call across the valley, hunt

and flirt with each other. Maybe, she says,

I hear more than one species these days.

Insects in the loft, perhaps. But I know she’s

thinking of the people who lived here before—

those we never met or the one we try to forget.

And of the loneliness of the nights

when she should be somewhere else.

It’s too safe for her here now, and today

she’s going out into the world again.

Soon I’ll be the one listening

to the roof expanding, contracting.

–Hannah Linden, from The Beautiful Open Sky

________________________

In case you missed it: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

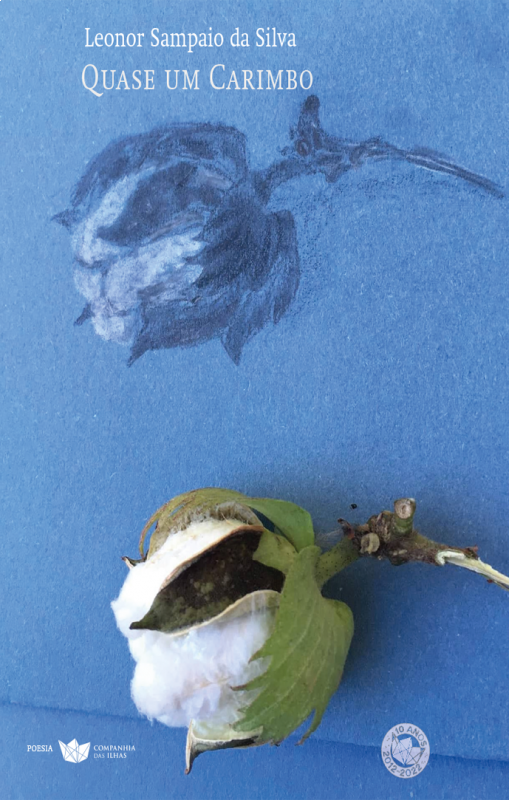

My friend and colleague Leonor Sampaio da Silva published her first collection of poems last summer, Quase um Carimbo (Companhia das Ilhas, 2022).

Born on the island of São Miguel, Azores, Leonor holds a master’s degree in Anglo-Portuguese Studies from the Universidade Novo de Lisboa and a PhD in Anglo-American Studies from the University of the Azores, where she has taught since 1991.

Having published a number of academic papers and contributions to various books, anthologies, and literary magazines, Leonor made her literary debut with a book of short stories, Mau Tempo e Má Sorte – contos pouco exemplares, which received the Daniel de Sá Humanities Prize in 2014. She is also the author of ABN da Pessoa com Universo ao Fundo (2017) and, with Carlos Carvalho, Pouca Terra – Fotografia e Literatura (2019).

“My idea for [this] book was to talk about the experience of isolation caused by the pandemic,” Leonor explained to me. “In which we lost contact with others and forced ourselves to face situations such as the vulnerability of life, how to make sense of each day, how to live with routine.”

Some of the poems read like diary entries, the poetic voice spoken by characters representing, as Leonor notes, “the others that exist within and outside of oneself.”

“Carimbo,” it may be useful to note, means “stamp,” the kind used to mark or authenticate official or private papers. Another meaning of the word, however, is “timestamp” (although usually written as “carimbo de data/hora.”) and, in this collection, each poem is marked by a timestamp: morning, afternoon, or night, as well as an action–I wake up, I sit down, I get up–as if to indicate stage direction.

It’s as if the characters in the poems are actors in their own play, marking their time, the pandemic imbuing even the most mundane tasks with the aspects of a theatrical production.

The book title translates as “Almost a Stamp,” which leads the reader to a question: if it is “almost,” what is it? An approximation? What is reality? The questions are heightened by the ending of the book where the theatrical stage suddenly becomes cinematic, play becomes film, language shifts in tone, the curtain falls, a wind picks up, a torrential rain pours down, and fallen leaves return to their trees. The speaker remains lonely. The book ends with one last action: “Adormeço” (I fall asleep).

“Poetry,” Leonor argues, “is a way of putting us in touch with each other and exploring new languages.” She carries this thread throughout the collection, whether using “the more intimate language of the diary/newspaper” or “the more social language of the theater,” demonstrating that “everything happens as if on a stage” and shielding us from loneliness and death.

Quase um Carimbo is an impressive debut poetry collection and I hope to translate more of it in the future.

Here are two poems by Leonor Sampaio da Silva in the original Portuguese and my translations into English:

manhã

acordo

uma personagem pragueja baixinho

pela noite mal dormida

o que farei se um Comboio transformar

a geografia deste lugar?

pensar no improvável tem sido

passatempo habitual

quase uma Obsessão

preocupa-me em demasia

a falta de uma Estação

—

morning

I wake up

a character curses softly

over the sleepless night

what will I do if a train transforms

the geography of this place?

thinking about the improbable has been

a regular hobby

almost an obsession

it worries me too much

the lack of a station

________

manhã

acordo

deve estar um dia quente a avaliar pela

temperatura do quarto

o corpo, o que é um corpo?

uma madeixa cortada

vivendo por um fio

enquanto aguarda reunir-se

à cabeça que dela se esqueceu

uma madeixa que se deixa

varrer

alisar

torcer em caracol

alourar ao sol

o sol, o que é o sol?

um corpo

—

morning

I wake up

it must be a hot day judging by

the temperature of the room

a body, what is a body?

a severed lock

living by a thread

while waiting to be reunited

with the head that has forgotten it

a lock that lets itself

sweep

smooth

twists into a curl

glistening in the sun

the sun, what is the sun?

a body

–Leonor Sampaio da Silva, from Quase um Carimbo

(translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

___

Speaking of the island of São Miguel: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

My dog Calvin died this year. He was fifteen and losing his ability to move. The last time I saw him, he was responsive, yet it was clear he was increasingly uncomfortable in his body. He always lit up when he saw me; sadly, I think he was always thinking, “At last you’ve come home.” I was not.

In fact, I lost Calvin in my divorce over 10 years ago and, after a few years of occasional visits in Brooklyn, I stopped getting to spend regular time with him. I know we both missed each other. (I’ve had a number of dogs in my life; we got Beverley in 2015 and, when she does something I wish she wouldn’t, I remind her that she’s neither my first dog nor my last.)

I wrote two poems about Calvin, both of which appear in the anthology, Dogs Singing. One, in the voice of Calvin, recounts his origin story, based upon what we were told by the PASPCA. The other is not so much about Calvin as about my growing restlessness in the home of my previous marriage. Calvin serves as a character, if not a symbol, along with mining bees and a redbud tree.

Because Calvin was put down earlier this year, Emily Berry’s poem, “Dream of a Dog,” which appeared originally in Granta last February and in her most recent collection, Unexhausted Time, struck a particular chord in me when I read it. Berry’s poem appears about a quarter of the way through the book and, after a series of untitled poems, it is the first poem with a title in the book and closes the book’s first, unnumbered section. (As readers, poets always look for things like this in a collection; there is usually a significance to such placements, signaling an intention on the part of the poet, as if to say, “pay attention to this one.”)

It’s also one of the few poems in the collection where, in the words of critic Steven Lovatt, writing in The Friday Poem, “the tone is for once gentle, undemonstrative and open to outside impressions.” Berry’s work has always struck me as characterized by a so-called “flat style,” which Noreen Masud, in an article in the journal Textual Practice, explains “involves postures of poetic melodrama which state themselves ‘flatly’, without apology.”

Berry’s “Dream of a Dog,” while it does use a flat style, also consists of one long sentence, or rather a fragment of a sentence, for it ends not with a full-stop period, but an ellipsis. The ellipsis hints there is more to come or, perhaps, that the reader could circle back to the beginning of the poem for it ends where it begins, with the words, “My life” as if the poem could be an endlessly cycling dream.

It also causes me to question, is it the “dream of a dog,” as in, the speaker is dreaming of a dog (line 19 begins, “if I had a dog”) or is it a dream a dog is having, complete with its sighs. (My dog Beverley barks in her dreams, along with sighs, and chases things; I wish I knew what.)

Emily Berry is the author of three poetry books published by Faber in the UK: Unexhausted Time (2022), Stranger, Baby (2017) and Dear Boy (2013). You can read more about her and her work at: https://www.emilyberry.co.uk/

Here is her poem, “Dream of a Dog”:

Dream of a Dog

My life, and all our lives, I said sleepily,

so soft now, like the neck of a sleeping dog,

I lay my hand on it, as you have lain your hand

on mine (on my life), this tenderly, as the dog

noses deeper into sleep, as she sighs the way

a dreaming dog does, I wish my life was in

your dream, dog, I think it is, and she turns

onto her back so her stomach rises pale and

softly furred, and your words are travelling

through me, or, no, they travel over me, the

way a breeze makes fabric touch us, the fabric

of half-drawn curtains billowing from an open

window, as I pass and glance out on such

a day, the dog whimpering softly in sleep;

perhaps it’s that you say I should have faith,

or that you have faith, in increments, while

my shoes are nosing through leaves and the

dog is alert or disappears (but she comes back),

if I had a dog she would be a kind of faith,

I would lift her onto my shoulder, the points

of her ears very elfin and her face, serious,

tilted to regard you, she would listen and run

and then, from a distance, up a slight incline,

when I call her, look back, then run on,

and I do believe in increments, as when

the dog brings me, in her dream, pinecones,

when she wriggles in my arms, her ribcage

strung like an archer’s bow, when her paws

bend at the wrist in supplication, I do not see

the slow wheels in my blood turning, but

I ride them, I do not see what I know

and everything beneath that, which I may

come to know, or may not, the slow slow

discernment of the deep layer, air bubbles

rising from the dead zone, the dog in her

dream talismanic on a hilltop, the soft tips

of her ears in sleep, a slight sigh, all my life.

–Emily Berry, from Unexhausted Time

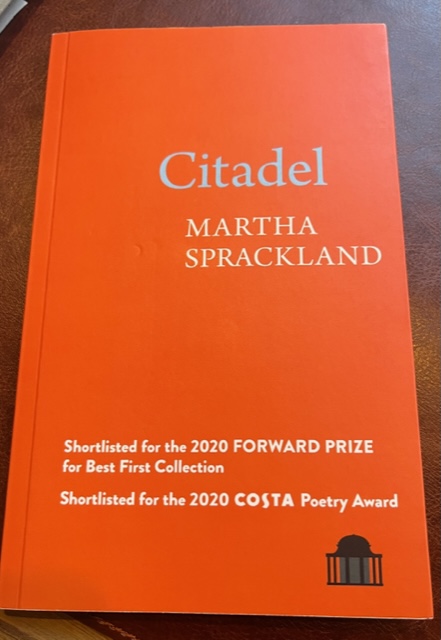

I stumbled across Martha Sprackland’s debut collection, Citadel, in Desperate Literature, a wonderful little bookshop off the Plaza Santo Domingo in Madrid last month. The poet, originally from Liverpool, now divides her time between London and Madrid, and she thanks the bookstore in the acknowledgments of her book. The collection intrigued me because of its size–a bit taller and thinner than the old City Lights paperbooks–and the paper wrapped around it proclaiming it as a staff favorite.

Inside, I found a captivating mix of poems that seemed to alternate between, as the back cover indicates, a “composite ‘I’–part Reformation-era monarch, part twenty-first century poet.” The monarch is Juana of Castile, “sixteenth-century Queen of Spain and daughter of the instigators of the Inquisition,” the so-called “Joanna the Mad.” The book was published in 2020 and shortlisted for the John Pollard International Poetry Prize in 2021, the Forward Prize for Best First Collection in 2020, and the 2020 Costa Poetry Award.

Cocido madrileño is a traditional stew from Madrid with meat and vegetables in a chickpea (garbanzo bean) base. I picked this poem to share because it is indicative of Sprackland’s gift for moving between the present and the past in this collection. I look forward to reading more of her work in the future.

Here is the poem in its entirety:

Cocido Madrileño

It was an unexplainable hunger, like a gravel pit,

and it wouldn’t go away. Sickness like a fingernail moon

around its darkness. Juana went to the bodega

and bought six tins of cocido ridged

like braziers, Litoral stamped in red along

the white coastline, the meats reclining

in an adoring harem of chickpeas.

Juana’s faith was on the wane but pork would prove it.

Morcilla, chorizo, tocino de ibérico, panceta,

soft white lard and blood and bone and smoke

tipped over the lip and into the pit, like a body

she desperately wanted to be rid of.

This, she believed, would sate her, save her.

–Martha Sprackland, from CITADEL

Learn more about the poet: Martha Sprackland

Click here to purchase Citadel directly from the publisher, Liverpool University Press.

Tonight, I’m reading from my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations in Terrain.org’s reading series. You can join us by registering here for the event. Hope to see you there!

I’ll be reading with two other poets, Joe Wilkins and Betsy Aoki. Betsy is an associate poetry editor with Terrain, which has published several of my poems over the years. Her colleague, Derek Sheffield, will be our host. Derek is a fine poet in his own right, and he has a new book out called Not For Luck, which poet Mark Doty selected for the Wheelbarrow Books Poetry Prize, and it was published by Michigan State University Press.

Derek has been called “a post-romantic nature poet,” in a recent review and, as the reviewer went on to say, his “poems are colored by a sense of separateness from nature and a recognition that language itself impedes any immediate communion with the world.” (Those of you familiar with my book Dwelling: an ecopoem, will understand why I find Derek’s work interesting and simpatico.)

I should also mention that he wrote a great blurb for my new book, for which I am truly grateful. And he has some of the longest poem titles I’ve ever seen (the one below is not even close to the longest), which is always fun.

Here is Derek Sheffield’s

“At the Log Decomposition Site in the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, a Visitation”

Below thick moss and fungi and the green leaves

and white flowers of wood sorrel, where folds

of phloem hold termites and ants busily gnawing

through rings of ancient light and rain, this rot

is more alive, says the science, than the tree that

for four centuries it was. Beneath beetle galleries

vermiculately leading like lines on a map

to who knows where, all kinds of mites, bacteria,

Protozoa, and nematodes whip, wriggle, and crawl

even as my old pal’s bark of a laugh comes back:

“He’s so morose you get depressed just hearing

his name,” he said once about a poet we both liked.

Perhaps it’s the rust-red hue of his cheeks

in the spill of woody bits. Or something in the long shags

of moss draping every down-curved limb. He’d love to be

right now a green-furred Sasquatch tiptoeing

among the boles of these firs alive since the first

Hamlet’s first soliloquy. He’d be in touch,

he said in an email, as soon as the doctors cleared him.

When this tree toppled, the science continues, its death

went through the soil’s mycorrhizae linking the living

and the dead by threads as fine as the hairs appearing

those last years along Peter’s ears, and those rootlets

kept rooting after. That email buried in my Inbox.

Two lines and his name in lit pixels on my screen.

What if I click Reply? That’s what he would do,

even out of place and time, here in the understory’s

lowering light where gnats rescribble their whirl

after each breath I send.

–Derek Sheffield, from Not For Luck, originally appeared in Otherwise Collective’s Plant-Human Quarterly