Last summer, I started a project to translate the Azorean poet Pedro da Silveira’s first book A ilha e o mundo (The Island and the World), which came out in 1952.

I had reviewed the late George Monteiro’s translation of Silveira’s last book, published in a bilingual edition by Tagus Press in the States and simultaneously by Letras Lavadas in the Azores in 2019 as Poems in Absentia & Poems from The Island and the World. In fact, the second half of that title was a misnomer; the book included only a few poems from Silveira’s first book–poems that had previously appeared in a Gávea-Brown anthology from the 1980s and sort of slapped on to the end of the book. (Silveira was born on Flores Island in 1922 and died in Lisbon in 2003.)

What struck me immediately about Silveira’s poetry—in Monteiro’s translation first and then in reading the facing Portuguese—was the depth of its feeling, the simplicity and directness of its language, and the brilliant tapestry woven by strands of memory, naming, and observations of nature. Indeed, all aspects that are found in my own poetry; hence, I felt a certain kinship with Silveira’s work straight away.

And yet, I was equally struck by the dearth of his poetry available in translation. How could such a seemingly important poet be so little represented in English translation? How much richer would the world of poetry–and the world of poetry-in-translation–be with Silveira’s body of work. And how much richer would be our lives in the Azorean diaspora with his sentiments, steadfast observations, and steady poetic hand.

I started with the second poem in the book, “Ilha”; this was likely the first poem I ever read by Silveira in translation, from that old Gávea-Brown anthology previously mentioned.

Here is the entire poem in its original Portuguese:

ILHA Só isto: O céu fechado, uma ganhoa pairando. Mar. E um barco na distância: olhos de fome a adivinhar-lhe, à proa, Califórnias perdidas de abundância.

As I tend to do in my method of translation, I first read the poem straight through and then wrote an impression or literal reading as I understood it:

Just this:

The closed sky, a heron

Hovering. Sea. A boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes guessing, at the prow,

Californias lost of abundance.

A bit clunky and prosaic, and probably unworthy. I prefer to not read another’s translation (if there is one) while translating a poem lest I be influenced by it, so Monteiro’s sat on the shelf.

One thing troubled me, however. The bird. Where did that heron come from? Surely, I remembered it from Monteiro’s version. “Ganhoa,” at first, I thought was a misprint of “ganhou” – who won? – but that made absolutely no sense, so I went with heron. But what was a heron doing in this scene? Were herons even found in the Azores?

Reluctantly, I checked Monteiro’s translation. Sure enough, there it was, “heron.” It struck a dissonant chord with me now. A heron. Really? Again, I wondered whether herons were found in the Azores and turned to the Internet.

Yes, there were at least ten species of heron that have been noted on these islands, including great blues and little egrets, which according to the website whalewatchingazores.com have been sighted, but “not regularly”; the species is classified as an “uncommon vagrant” on the islands. And, most recently, a confirmed sighting of another species, the yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) was described in a scientific paper by João Pedro Barreiros. Most likely, however, this one was blown east by a strong, errant wind from the west. Several herons were known to stop-over on their migratory path from Africa to northern climes and back.

Still, heron didn’t seem correct, to me, given the scene described. The use of Mar all alone. And the boat seemed to imply open waters rather than shoreline.

Herons are marsh-dwelling, shoreline species for the most part, so I was perplexed why they might be hovering “at Sea” or the “open ocean,” as I envisioned it. Were they blown off-course and out of their range? That would surely change the nature of this poem, which I assumed was about emigration or the emigrant returned or the desire to emigrate but also remain tied to the island. If it was not a heron, what was it then? What else might “hover” over the open ocean?

I typed “ganhoa” into Google. The almighty, all-seeing Google asked if I meant “ganhos” earnings; no, I did not. This was not a poem set in the halls of finance or a casino in Monaco. So, I clicked on “search instead for ganhoa” and up came a page from Priberam dicionário. I had my bird! The yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis atlantis)…surely this bird would hover over the prow or bow of the boat, and even the stern, looking for a handout. A ganhoa recupera os seus ganhos. (The gull recovers its winnings.)

Here is my version of Pedro da Silveira’s “Island”:

Just this:

The closed sky, a yellow-legged gull

hovering. Open ocean. And a boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes, at the bow, divining,

lost Californias of plenty.

(Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

____

(This text was adapted from a paper delivered at the Colóquio celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pedro da Silveira, “Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedro cultural,” at the University of the Azores in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, in September 2022.)

Speaking of the Azores: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

Perseverance and my poem “An ‘Unkindness’ of Ravens”

June 9, 2012

I lived in Alaska sixteen years ago, when my oldest son Jasper was born.

During his first month he had trouble sleeping, as babies often do, and most nights found me walking with him in my arms trying to get him back to sleep.

While walking I would softly sing to him and recite poems and, occasionally, I would whisper a poem I was working on at the time.

One of these poems was “An ‘Unkindness’ of Ravens,” which was filled with direct observations of ravens — an almost constant presence in town and, along with polar bears, a kind of totem in my life since I first saw them as a boy in Maine.

The poem started forming one night when, after putting my son back in his crib, I couldn’t get back to sleep.

Looking out the window, I noticed ravens gathering in the tall trees behind the house. I was intrigued as their numbers grew and the poem began to unfold in my mind.

Many of the images in the poem came from ravens I observed out my office window in the old Alaska Railroad Depot building by Ship Creek below downtown Anchorage.

I always liked this poem, perhaps because of its association with the birth of my first child and what it said about the strangeness and newness of my life at the time: a new father and new to Alaska; both uncharted territories.

As with many things, my perseverance paid off and, fourteen years after it was written, the poem found a home in a journal called Abyss & Apex.

Here is my poem, “An ‘Unkindness’ of Ravens”:

To fall asleep at night, I count ravens

from my bedroom window.

They gather in the spruce trees

at the edge of the woods,

as snow gathers dusk on its surface.

By midnight, thirty or forty

have gathered there in the oily dark.

As a group, they are called “an unkindness,”

but they are polite

and helpful to each other,

share their successes and failures

pursue joy and embrace their strength

in numbers, which is more than we can say.

Plummeting downhill, they launch into air,

as if snowboarding; flipping and spinning

— hell-bent teenagers on a half-pipe.

In more sober moments, they tell each other

where to look for food, when danger is near,

and where the good garbage is. They discuss

variable wind speeds or compare moose meat

found in the woods with that of roadside kills.

They can be graceful on the wing — Naiads

of the air — or clumsy and indelicate,

half-eaten bagels dangling from black beaks.

Dusk comes later and later these evenings,

and morning arrives sooner, winter almost over.

Come Easter, the ravens will be gone.

Ravens prefer dead things remain dead.

–Scott Edward Anderson

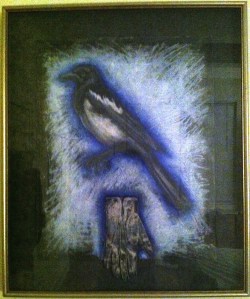

Magpies, Alaska, and my poem “Naming”

July 9, 2010

Almost a decade ago, the Alaska Quarterly Review published a poem of mine called “Naming.” I thought of it today because a good friend mentioned it in a message to me on Twitter. (She had overheard a conversation about magpies I was having with another friend.)

I’m not around magpies much these days, living on the East Coast. I miss them. Magpies, all corvids, really, are a totem for me (bears, especially polar bears are my other totem). Highly intelligent birds with bad reputations, they are a lot of fun.

Gary Snyder once told me and a group of other students that we should find totems for our poetry, “this is the world of nature, myth, archetype, and ecosystem that we must all investigate.” He also told us to “fear not science,” to know what’s what in the ecosystem, to study mind and language, and that our work should be grounded in place. Most of all, he instructed, “be crafty and get the work done.”

Advice that also, curiously enough, reminds me of magpies.

Here is my poem “Naming”:

The way a name lingers in the snow

when traced by hand.

The way angels are made in snow,

all body down,

arms moving from side to ear to side to ear—

a whisper, a pause;

the slight, melting hesitation–

The pause in the hand as it moves

over a name carved in black granite.

The “Chuck, Chuck, Chuck,”

of great-tailed grackles

at southern coastal marshes,

or the way magpies repeat,

“Meg, Meg, Meg”–

The way the rib cage of a whale

resembles the architecture of I. M. Pei.

The way two names on a page

separated by thousands of lines,

pages, bookshelves, miles, can be connected.

The way wind hums through cord grass;

rain on bluestem, on mesquite–

The tremble in the sandpiper

as it skitters over tidal mudflats,

tracking names in the wet silt,

silt that has been building

since Foreman lost to Ali,

since Troy fell — building until

we forget names altogether–

The way children, who know only

syllables endlessly repeated,

connect one moment to the next by

humming, humming, humming–

The way magpies connect branches

into thickets for their nesting–

The curve of thumb as it caresses

the letters in the name of a loved one

on the printed page, connecting

each letter with a trace of oil

from fingerprint to fingerprint,

again and again and again—

Scott Edward Anderson

Alaska Quarterly Review, Summer 2001

Here is an Mp3 recording of me reading “Naming” Live at the Writers House, University of Pennsylvania, on September 22, 2008: Scott Edward Anderson’s “Naming” (Note: there is a 10-second delay at the beginning of the file.)

Postscript: And here is a filmpoem of “Naming” made by Alastair Cook in 2011: Naming