I’ve been writing these National Poetry Month emails/posts for the past 27 years and each year I think it’s going to be my last. Will anyone miss them if I stop? Does anyone really read them? But then I get such great messages in response to a post, and it keeps me going. Sometimes, I hear from someone I haven’t heard from in a long time, and it makes all the difference.

Today, I got a phone call from an old friend, Andrew Coulter, in Wyoming—we go back to our early days with The Nature Conservancy over 30 years ago. He called me after having read my Week Four post and explained he was going to send me an email to tell me how much he enjoyed getting the poems every year. But then he thought, “I’ll just pick up the phone and call him.”

We talked for about half an hour, got caught up on each other’s lives, and had a few laughs over some of our shared stories and history. I know we both hung up with smiles on our faces. It’s a good reminder to reach out to people we care about—we’re all so busy that it’s easy to lose touch, to let the years pass by without connecting with old friends.

Andrew’s call also reminded me that I usually post a Bonus Week poem, typically one of my own, at the end of every Poetry Month. “You can have a Bonus Poem in May,” Andrew said. So, why not? Here goes. (Thanks, Andrew.)

My poem “Doubting Finches” started, like many of my poems, from a simple observation made in 2009. A pair of house finches had set up a nest in the porch light of my old house in Philadelphia. I had the image of the nesting house finch couple and the intricacy of what I observed in the nest, but it didn’t amount to much more. I worked on the poem for quite a while before it came together—a few years, actually —and it finally went beyond the original inspiration.

The poem languished until I found there was more to the story. This was around two years later, at the tail end of a marriage, and I was about to embark on a new life where that house would no longer be mine. It was a time of turmoil, uncertainty, grief, and yet, also, a certain joy and anticipation. I wasn’t running away from something this time; I was running towards something.

The finished poem appeared in the UK online journal, Zoomorphic, in 2017, thanks to the wonderful Welsh poet, Susan Richardson. It also appears in my book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations, published by Shanti Arts in 2022.

Here is my poem, “Doubting Finches”:

The house finch nest in my porch light

has a curious architecture,

made entirely of found things:

dried seed heads from last year’s columbine,

dusky strands of my daughter’s hair,

small sticks, rose thorns, bits of string,

a gold thread from a cigarette pack wrapper.

Inside, wool-lined, cotton and fleece,

it holds three eggs, blue with tawny flecks.

The female finch sits on the nest

for an unusually long time; so long,

I fear she is mistaken or my messing

with the nest has disrupted gestation.

She picked her mate for the redness

of his head and chest, proxy for feeding prowess.

(I guess.)

In a few weeks all will be gone:

cherry blossoms drifting on air,

dogwoods blooming, oaks leafing out,

and the female finch finding another mate,

to start a second family this season.

Who was it that said, “Doubt is a privilege

of the faithful”? At least, I think someone

said it or should have. Then it was me,

me finding another mate, another home,

another reason. And I saw they swept out

the finch nest from that old porch light

as soon as I was gone.

–Scott Edward Anderson

Ekphrastic Poems: Can they stand alone?

February 26, 2011

Black Angus, Cooperstown by Paul Niemiec, Jr. (used by permission of the artist)

Caroline Mary Crew, writing about ekphrastic poetry in her always engaging blog, Flotsam, asks, “Can the poem stand apart from the painting?”

She cites some worthy examples of various approaches and “types” of ekphrastic poems, including famous examples by Auden, Keats, and O’Hara, as well as a poem that was completely unknown to me, Monica Youn’s “Stealing The Scream.”

I was intrigued by Caroline’s question and sent her an example of my own, “Fallow Field,” which was not quite an ekphrastic poem by strictest definition — that is, a poem that comments upon another artwork, because Joshua Sheldon’s photograph and my poem were created at the same moment.

It occurred to me that another of my poems, “Black Angus, Winter,” was also a kind of ekphrastic poem, of the type Caroline categorizes as narrative/monologue.

This poem, which was part of a group that won The Nebraska Review Award, was inspired in part by the landscape of central New York State, where I spent summers in the mid-1980s. There was much to inspire: rolling hills, dairy and cattle farms, cornfields, and old, often dilapidated farm buildings.

The poem also found inspiration and a launching-off point in a painting by a friend, Paul Niemiec, to whom the poem is dedicated. (Reproduced above.)

Here is my poem

“Black Angus, Winter”

I.

The angus rap their noses

on the ice–

fat, gentle fists

rooting water

from the trough.

They kick up clods of dirt

as a madrigal of shudders

ripples their hides.

II.

The barn needs painting,

it’s chipped like ice

from an ice-cutter’s axe.

The fence also needs work,

posts leaning, wire slack.

The Angus keep still–

they’re smarter than we think,

know all about electricity.

III.

I cross the barnyard

on my way back from the pond,

ice skates keeping time

against the small of my back.

The sting of the air

is tempered by the heat of manure.

Through the barn door:

Veal calf jabbing at her mother’s udder.

(For Paul Niemiec)

–Scott Edward Anderson

##

When the Spirit Moves You, Go With It

November 18, 2010

Back in November 2002 I was a poet-in-residence at the Millay Colony in upstate New York. I went up there with the kernels of a big, ambitious new project in mind — my poetic sequence called “Dwelling.”

One day, November 17th to be exact, I took a break from writing and went for a hike in the woods. In the middle of the woods I had a kind of vision of my childhood.

I was in the woods with Gladys Taylor, who we called Aunt Gladys and who looked after me those days. Really, I was her protegé. (I have two slim books of stories she wrote about my exploits as a toddler.)

Suddenly, as rarely happens, I had one of those bolts of inspiration and was compelled to run back to my studio. I sat down at the desk, grabbed my notebook, and wrote furiously. Some 250 lines later, I put down my pencil and went to the communal dining hall. When I got back after dinner and read what I had written, I thought some of it was pretty good.

The best of it was the story of Gladys’s “education” of me — I always say that everything I learned, I learned from Gladys Taylor.

Wanting to acknowledge Gladys in a dedication, I looked up her birth date on the Social Security Death Index (she died in 1986). It turned out, I was writing the poem on what would have been her 100th birthday! (This past Wednesday would have been her 108th.)

As a dear friend of mine said to me once, “Coincidence is God’s way of remaining mysterious.”

Here is my poem, which was a runner-up for the Robert Frost Foundation Poetry Award a few years ago:

The Postlude

“What dwelling shall receive me?…The earth is all before me.”

–Wordsworth, “The Prelude”

I am a child, crawling around in the leaves

With Gladys Taylor while she names the trees,

parts the grasses, digs into the earth with a gardener’s trowel.

She picks out worms and slugs, millipedes

And springtails, which we see with a “Berlese funnel.”

Busy decomposers working their busy tasks,

Turning waste into energy, leaf litter into soil again.

Gladys names things for me: “That oak,

That maple there, that sassafras, smell its roots.”

“Root beer!” I exclaim,

Her laughter peeling away into the hills. Later,

With Comstock’s Handbook of Nature Study

On the table next to the unending jigsaw puzzle,

Gladys opens to “The Oaks,” reading or reciting:

“The symbol of strength since man first gazed

Upon its noble proportions…” Then she sings Virgil,

Full in the midst of his own strength he stands

Stretching his brawny arms and leafy hands,

His shade protects the plains, his head the hills commands.

Leaves and acorns spread across the table,

Each divided to its source, as if cataloguing specimens:

The white and chestnut oaks, red and scarlet,

Every oak in the neighborhood, sketching the leaves,

Tracing and coloring them. Then questions, such questions:

“Where did we see this one growing?” “How tall?”

“Are the branches crooked or straight?”

“Round leaves or pointy?”

And then a game of matching

Acorn to leaf; a most difficult lesson — as difficult

As those jigsaw puzzles for a boy lacking patience

Or attention. Outdoors again, to learn attention,

Naming the birds that came to eat at the feeder:

Chickadee, sparrow, nuthatch, tufted titmouse,

The ubiquitous jay.

“The mockingbird, hear

How he makes fun of all the other birds.” Now

Thrasher, now robin, the sweet sweet sweet,

Very merry cheer of the song sparrow,

Or the flicker’s whicka whicka wick-a-wick.

Then a jay’s piercing caw, a cat’s meow,

This was all the mocker’s doing! And wide-eyed,

I stare, as Gladys seems to call birds to her side.

“The robin tells us when it’s going to rain,

Not just when spring is come,” she says. “Look

How he sings as he waits for worms to surface.”

That summer, rowing around the pond

By Brookfield’s floating bridge, I saw a beaver

Slap the water with its tail, and then swim around the boat,

As if in warning. Under water a moment later he went,

Only to appear twenty yards away, scrambling up the bank,

Back to his busy work. “Busy as a beaver,” Gladys laughs.

Then a serious tone, “You know that beavers gathered

The mud with which the earth was made?”

(I later learned this was Indian legend; to her

There was little difference among the ways of knowing.)

All around the pond the beavers made of the creek,

The sharp points of their handiwork: birches broken

For succulent shoots, twigs, leaves and bark bared.

“When they hear running water, they’ve just got

To get back to work!” Beavers moving across

The water, noses up, branches in their teeth,

Building or repairing dams or adding to their lodges,

Lodges that look like huts Indians might have used.

I watched for them — beavers and Indians — when

Out on the water, and once I remember a beaver

Jumping clear out of the water over the bow of the rowboat!

Later, wading in the mud shallows by the pond’s pebbly edge,

I came out of the water to find leeches covering my feet,

Filling the spaces between my toes. Screaming, fascinated,

I learned that they sucked blood, little bloodsuckers,

A kind of worm, which were once used to reduce fever.

That was me to Gladys Taylor’s teaching,

Wanting to soak up everything she had to give me.

We picked pea pods out of the garden, shelled

On the spot, our thumbs a sort prying-spoon,

And ate blackberries by the bushel or bellyful,

Probably blueberries, too, I don’t know. And

Seeing the milkweed grown fat with its milk,

I popped it open, squirting the white viscous

Juice at my brother. Gladys always found

A caterpillar on the milkweed leaves, tiger stripes

Of black, white, and yellow. “Monarchs,” she said,

“The most beautiful butterfly you’ll ever see.”

I looked incredulously at the caterpillar, believing,

Because she was Gladys, but not believing her,

That this wiggly, worm-like thing could be a butterfly.

Later, she found a chrysalis and took the leaf

And twig from which it hung. She placed it atop

A jar on the picnic table, and each day we waited

— waited for what? I didn’t know. Until one day,

It was empty, a hollow, blue-green emerald shell,

And I almost cried. “Look, out in the meadow,”

She instructed. Hundreds, it seemed like

Thousands, of monarch butterflies flitting about,

From flower to flower!

The wooly-bear

Was easier to study. We put it in a jar with a twig

And fresh grass every day; it curled and slept and ate

Until one day it climbed, climbed to the top

Of the twig and spun a cocoon from its own hairs.

There it stayed for weeks, until at last I thought it dead.

But then, emerging from its silky capsule, a hideous sight:

Gray, tawny, dull–a tiger moth! Nothing like the cute

And fuzzy reddish-brown and black teddy bear we’d found.

“This is magic,” said Gladys. “Nature’s magic.”

And I believed her, believe her still, that there is some magic

In nature speaking within us when we are in it, of it, let it in–

Science may explain this all away, physics or biology,

But nothing will shake my faith in this:

That the force of nature, the inner fire, anima mundi,

Gaia, or whatever you may call it, is alive within each

Being and everything with which we share this earth.

My Mother Earth was Gladys Taylor, and she

Taught me these things, and about poetry and art,

In the few, brief years we had together. Gladys

Taught me how to look at the world — to pay attention.

Thus began my education from Nature’s bosom:

A woman, childless herself (I believe) who,

In her dungarees and work-shirt, took a child

Under her wing and gave him gold,

Gave him his desire for dwelling on this earth.

(For Gladys Taylor, 17 November 1902-18 March 1986)

–Scott Edward Anderson

Two Poems of the Beach

August 1, 2010

I’ve been on vacation this past week on the North Carolina Coast.

Oak Island is one of the south-facing islands that are not part of the more famous Outer Banks and neither as far south nor as celebrated as Myrtle Beach.

We like it there because it is quiet and sleepy in an old-fashioned way. It is a far drive from Philadelphia, but these days you need to go pretty far to get far away.

Being on the beach reminded me of two poems I wrote about other Atlantic Coastal vacations, back in the early 90s.

The first, “Gleanings,” was written in Ocean Grove, New Jersey, and appeared in an anthology called “Under a Gull’s Wing: Poems and Photographs of the Jersey Shore.” It was written for two old friends, Jim Supplee and Diane Stiglich:

“Gleanings”

Look at the two of them, bent

to the early morning tide.

They cull glass from the sandy surf.

Strange and wonderful alchemists,

who search for the elusive blue

of medicine bottles, caressing

emerald imitators from “Old Latrobe,”

or amber sea urchins

left there like whelks at low tide.

They discard broken bits of crockery,

forsaken like jetsam of the sands.

Beach glass is opaque

with a false clarity:

Polished by sand and sea,

the edges don’t cut

like our lives, lived elsewhere,

out beyond the last sandbar,

where plate tectonics rule the waves.

The second poem was written down the coast a bit in Chincoteague, Virginia. Chincoteague is famous for its wild horses and for its mosquitoes. But I chose a couple of other focal points in my poem “Spartina,” which later appeared in the magazine Philadelphia Stories:

“Spartina”

Herring gull dragged from the cordgrass by a bay cat,

who drops the sputtering gull under a tree.

The gull’s left wing and leg are broken — right wing thrashing,

body turning round a point, compass tracing a circle.

Wild chorus of gulls tracing the same circle in salt haze

only wider, concentric, thirty feet overhead.

The cat lying down in shade, making furtive stabs,

powerful paws slapping down motion.

The cat’s feral, calico-covered muscles ebb and shudder

in the bay breeze. She is Spartina, waving in wind or water.

Now she yawns indelicately, fur and feathers

lofting on the incoming tide.

The gull plants his beak in the sand,

tethered, like all of us, to fate.

–Scott Edward Anderson

##

I hope your vacation plans take you to a coast somewhere. “The sea is a cleanser,” as a good friend wrote to me recently.

Let’s hope that’s true, for the sake of the Gulf Coast.

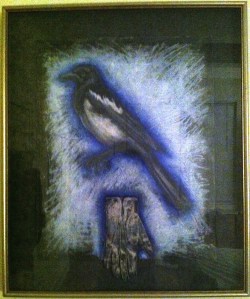

Magpies, Alaska, and my poem “Naming”

July 9, 2010

Almost a decade ago, the Alaska Quarterly Review published a poem of mine called “Naming.” I thought of it today because a good friend mentioned it in a message to me on Twitter. (She had overheard a conversation about magpies I was having with another friend.)

I’m not around magpies much these days, living on the East Coast. I miss them. Magpies, all corvids, really, are a totem for me (bears, especially polar bears are my other totem). Highly intelligent birds with bad reputations, they are a lot of fun.

Gary Snyder once told me and a group of other students that we should find totems for our poetry, “this is the world of nature, myth, archetype, and ecosystem that we must all investigate.” He also told us to “fear not science,” to know what’s what in the ecosystem, to study mind and language, and that our work should be grounded in place. Most of all, he instructed, “be crafty and get the work done.”

Advice that also, curiously enough, reminds me of magpies.

Here is my poem “Naming”:

The way a name lingers in the snow

when traced by hand.

The way angels are made in snow,

all body down,

arms moving from side to ear to side to ear—

a whisper, a pause;

the slight, melting hesitation–

The pause in the hand as it moves

over a name carved in black granite.

The “Chuck, Chuck, Chuck,”

of great-tailed grackles

at southern coastal marshes,

or the way magpies repeat,

“Meg, Meg, Meg”–

The way the rib cage of a whale

resembles the architecture of I. M. Pei.

The way two names on a page

separated by thousands of lines,

pages, bookshelves, miles, can be connected.

The way wind hums through cord grass;

rain on bluestem, on mesquite–

The tremble in the sandpiper

as it skitters over tidal mudflats,

tracking names in the wet silt,

silt that has been building

since Foreman lost to Ali,

since Troy fell — building until

we forget names altogether–

The way children, who know only

syllables endlessly repeated,

connect one moment to the next by

humming, humming, humming–

The way magpies connect branches

into thickets for their nesting–

The curve of thumb as it caresses

the letters in the name of a loved one

on the printed page, connecting

each letter with a trace of oil

from fingerprint to fingerprint,

again and again and again—

Scott Edward Anderson

Alaska Quarterly Review, Summer 2001

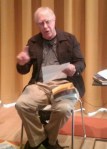

Here is an Mp3 recording of me reading “Naming” Live at the Writers House, University of Pennsylvania, on September 22, 2008: Scott Edward Anderson’s “Naming” (Note: there is a 10-second delay at the beginning of the file.)

Postscript: And here is a filmpoem of “Naming” made by Alastair Cook in 2011: Naming

Robert Hass and sharing poetry among generations

May 31, 2010

A curious thing happened to me yesterday in New York City. Robert Hass read at Poets House and gave a program for children in the morning. I took my six-year-old son, Walker, with me because he’s started writing poems (he’s got me beat by 3 years!) and we spent the day in the City alone together.

When I told Walker we were going to see and hear one of my poetry teachers, he said, “That’s cool, because he taught you and now you’re teaching me and when I have children I’ll teach them…it’s like we’re keeping it going.”

Indeed, it felt like that when I introduced Bob to my son. Bob has grandchildren Walker’s age and it wasn’t lost on me that there was something transpiring between our three generations.

Walker brought one of his poems to share with Bob and handed it to him in an envelope. During the program, in which Bob was reading poems by children from his River of Words project, he pulled out Walker’s poem and asked if Walker wanted to read it. Walker shyly declined and Bob asked for permission to read it to the audience. Walker beamed. (So did I.)

Bob read Walker’s poem and declared, “This is a real poem.” We both smiled. It was a magical moment to have a mentor appreciate the work of your son. I was really feeling blessed that morning.

Later, after wandering around Tribeca and the wonderful riverside parks along the Hudson, Walker and I sat on the rocks behind Poets House in the newly opened South Teardrop Park and listened to Bob and his wife Brenda Hillman read their poems into the late afternoon. What a magical day.

Here is Walker’s poem, “The Snow I’ve Been Waiting For”:

The Snow that crunches beneath my feet.

Oh the wonderful snow, snow, snow.

The snow that tastes so wonderful.

The snow, the snow, the snow.

The snow I’ve been waiting for all along,

The snow I’ve been waiting for all year.

The snow, the snow, the snow.

The Snow I’ve been waiting for.

–Walker Anderson, 6

Related articles by Zemanta

For the past 13 years I’ve been sending out a poem-a-week email during National Poetry Month. Each week, I introduce a poem to readers on the list, which is now over 300 strong.

At month’s end, I’m always asked to extend it beyond the month of April. In lieu of that, I think I’ll publish poems from the series here from time to time, as long as I can get the poets’ permission.

(If you’d like to subscribe to the list for next year, send me an email at greenskeptic[at]gmail[dot]com.)

#

My friend Lee Kravitz — whose memoir, Unfinished Business: One Man’s Extraordinary Year of Trying to Do the Right Things, comes out next month — is a great reader of poetry.

So when he handed me a book of poems at Thanksgiving last year, I knew it would be worth reading.

He told me two things about the book: it was written by another good friend of his and she was an intensive care physician in Washington, DC.

The book was Night Shift by Serena J. Fox. And one thing you quickly learn from her poems is that Dr. Fox is no Dr. Williams making house calls in a small, northern New Jersey community. She started her career in the emergency room of Bellevue Hospital in New York City, one of the busiest ERs at the time – the early era of AIDS.

(I had an experience at Bellevue in the early 80s – probably while she was in residence there — involving an attempted suicide by a neighbor. It was not a fun place to be back then.)

As a poet, Fox has an uncanny ability to apply her poetic sensibility to the reality she witnesses through her work. I admire the way she seamlessly weaves medical terminology – a rare gift that perhaps only Jane Kenyon mastered before her – and the harshness of life as she sees it into a poetry that transcends reportage.

Fox tackles a variety of forms and styles from traditional lyrics to fragments and more experimental sequences. And she is equally adept at short and long forms — her long poems, including the title poem, “Northeast Coast Corridor,” “Blood Holies,” and “551,880,000 Breaths” are remarkably varied and sustained collages of images and information, stories and voices overheard.

How glad I am that Lee introduced me to her work and pleased that I can introduce a sample of it to you here.

Here is Serena Fox’s poem,

The Road to Çegrano, 1999

(with Patch Adams and Clowns, Skopje, Macedonia)

Pinpricks of poppies

Populations

Of them—

Supra-oxygenated

Arterial

Oblivious to

Camps and tents

Of no interest to

Scythes

Unregulated

Flaunting bright

Points in

Grass and fields—

The other side of

Fences.

In the camps

Children

With blackbird

Beak eyes

Scavenge trinkets

Touches

Kisses from

Strangers—

A busload of

Ferocious

Clown-doctor

Revolutionaries

Carrying

Medical

Supplies and

Angry

Armloads of

Peace.

One-on-one

With the villagers—

Six thousand here

Thirty-nine thousand

There—

Dust

Is the only

Accumulation—

Rust-colored

Covering the tents

And doctors

Without borders.

The clown-doctors

Come armed with

Red rubber

Noses

Electric-blue hair.

The kids riot for

Stickers

Attention.

They quiet for

Bubbles

Blown gently

Balloons

For the boy

Leg in a

Cast

Group photos

Promises to send

Pictures.

Thank G’d the

Fighting

Stopped.

What would they have

Done in winter

Summer?

But where to send

Them?

Back to the

Burning?

Over the fence

The fields?

Out toward the

Mountains—

Bubbles

Balloons

Boys, girls, bombs,

Poppies?

–Serena Fox, from Night Shift

(Copyright Serena Fox. Reprinted with permission of the author)

——————————————————–

Serena sent me this note about the poem: “In May of 1999 I joined Patch Adams for a one-week trip to Macedonia and the refugee camps holding thousands of people who had scaled snow-covered peaks to get out of Kosovo. We were an eclectic assortment of clown-doctors who had traveled with Patch before and others like me who hoped to contribute in some small way to soothing the chaos going on in the former Yugoslavia.

I thought I was going to deliver intravenous supplies and help set up a clinic outside the camps for women. I also ended up roving the camps with children of all ages and forgoing my usual reserve for my first red rubber nose and a blue wig. As usual the people I met gave me infinitely more than I could ever give back. I was impressed by the efficiency and cleanliness of the UN sponsored camp.

The most vivid sensory memory is that of the foothills covered with poppies, women in the fields wielding scythes, the slowing of time and the redness of the poppies which had the exact quality, for me, of arterial blood.” –SJF

Valentine’s Day: A Frostian Dilemma

February 14, 2010

Last week the delightful Scottish poet Elspeth Murray posted some photographs of a trail intersection on Twitter. She referred to it as “a Robert Frost type dilemma.”

She reminded me of my poem “Reckoning,” which describes another Frostian dilemma. Written almost twenty years ago, “Reckoning” is a poem about the difficulties that visit a young couple when one of them is having doubts about their path forward.

Sometimes the choice we make is the wrong one. Sometimes, even when our choice extends the journey beyond what we anticipated, it turns out the right one.

(I should say here that the couple depicted in the poem recently celebrated their 18th wedding anniversary.)

Here is my poem, “Reckoning”:

RECKONING

Camel’s Hump, Vermont, 4083′

I.

Your abacus of worries,

me, counting my own pace, afraid

of the one real thing

I’ve known in years–

Negotiating our vertiginous October,

up through birch, maple, oak, cedar, white pine;

granite rising like barnacles on a humpback.

How do you stay calm?

Conceit hangs from my pack

like an extra water bottle.

I have trouble listening:

Do you want to push me over the summit,

or knock me out with a chunk of granite?

The mountain is not mine, I fool myself

when I play the king.

II.

We get turned around, tricked by language:

The ring of civilization in “Forest City,”

or the sylvan slur of “Forestry.”

The wrong trail is the one I’ve chosen–

And through the muddle, darkness comes,

and fourteen miles is the double of seven.

We switchback over the mountain’s bulge

and bushwhack round its base,

hours multiplied by circumference.

III.

At last back at camp,

we learn to count on each other.

From the stone house meadow:

Our prankster’s rising hump.

We curse and praise its witchery.

On that rock-ribbed blackberry hill

of Vermont’s quiet reckoning, we

calculate the chalk silhouette

in a moonlit night’s

heavy charcoal horizon.

–Scott Edward Anderson

(This poem appeared in Earth’s Daughters journal in 1997.)

Recession or Bust

December 29, 2009

“Taps” fills the foggy night air

From The Netherlands Carillion,

Overlooking Arlington

National Cemetery,

As Ben Bernanke tolls

the death knell

For the American economy.

“They know nothing,” shouts

The sound effect button

Pounded by Jim Cramer

on “Mad Money.” They do.

Know nothing, that is.

I hit the snooze button

Almost as often.

O, what sacrifices we make,

Neglecting the illusionary line

Between light and darkness,

Between loss and triumph.

#

I started this poem in the summer of 2008, just before the collapse of the US economy. Just ran across it as I was reviewing my poetry production over the past year.

Not sure it works, exactly, but in terms of subject matter and approach it foreshadowed some of the poetry I wrote this past year.

Happy New Year.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)