WINE-DARK SEA BOOK LAUNCH & READING

March 2, 2022

In conversation with Kathryn Miles

On #pubday eve, Kathryn Miles and I got together to chat about my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. We had a wide-ranging conversation about the book, specific poems, finding love at middle age, the idea of home, and the Azores — and I even read a poem in Portuguese.

Have a look here:

The book came out March 1st and is available through the links on my website: scottedwardanderson.com/wine-dark-sea

Answering the Proust Questionnaire

February 1, 2016

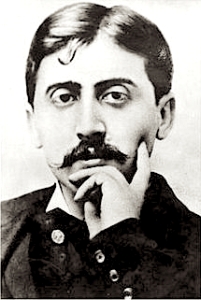

Marcel Proust

Legend has it that 13-year-old Marcel Proust answered fifteen questions in the birthday book of Antoinette Felix-Faure. Seven years later, at another social event, he completed another questionnaire. Ah, parlor games!

Over the years, Vanity Fair and other magazines have featured a version or another of this questionnaire, now called the “Proust Questionnaire.”

In the wake of David Bowie’s death last month, his answers to the Vanity Fair version were circulated by Maria Popova on her wonderful Brain Pickings blog.

I decided it would be fun to answer a version that closely approximates the original version Proust completed.

Name: Scott Edward Anderson

Date the questions were answered: 30 January 2016

Age: 52

Village / Town / City you live in: Brooklyn, NY

Occupation: Consultant and Poet

(The questions include Marcel Proust’s answers)

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

Proust: To be separated from Mama

Scott Edward Anderson (SEA): To be without love.

Where would you like to live?

Proust: In the country of the Ideal, or, rather, of my ideal

SEA: I’m happy where I am right now in Ditmas Park, Brooklyn. It feels like home to me.

What is your idea of earthly happiness?

Proust: To live in contact with those I love, with the beauties of nature, with a quantity of books and music, and to have, within easy distance, a French theater

SEA: Cooking and eating a good meal with my wife after a nice long hike in the woods, enjoying a great glass of wine or a Hendricks martini, and retiring to the living room to read some poetry or listen to favorite music by the fire.

To what faults do you feel most indulgent?

Proust: To a life deprived of the works of genius

SEA: I am intolerant of ignorance and authority and, most especially, ignorant authority.

Who are your favorite heroes of fiction?

Proust: Those of romance and poetry, those who are the expression of an ideal rather than an imitation of the real

SEA My favorite heroes are always creative travelers in strange lands who survive by their wits and wiles.

Who are your favorite male characters in history?

Proust: A mixture of Socrates, Pericles, Mahomet, Pliny the Younger and Augustin Thierry

SEA: Teddy Roosevelt

Who are your favorite heroines in real life?

Proust: A woman of genius leading an ordinary life

SEA: Billie Holiday and Elizabeth Bishop

Who are your favorite heroines of fiction?

Proust: Those who are more than women without ceasing to be womanly; everything that is tender, poetic, pure and in every way beautiful

SEA: Same as heroes: Creative travelers in strange lands who survive by their wits and wiles.

Your favorite painter(s)?

Proust: Meissonier

SEA: Monet and Vermeer

Your favorite musician?

Proust: Mozart

SEA: The Beatles

The quality you most admire in a man?

Proust: Intelligence, moral sense

SEA: Integrity and creativity

The quality you most admire in a woman?

Proust: Gentleness, naturalness, intelligence

SEA: Integrity and creativity

Your favorite virtue?

Proust: All virtues that are not limited to a sect: the universal virtues

SEA: Diligence

Your favorite occupation?

Proust: Reading, dreaming, and writing verse

SEA: Add walking in the woods to what Proust said.

Who would you have liked to be?

Proust: Since the question does not arise, I prefer not to answer it. All the same, I should very much have liked to be Pliny the Younger.

SEA: A better friend to some, a better man at times, a better husband to my wife, and a better father to my children.

#

Final 5 Questions for Poets

June 13, 2014

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

I’ve tried to answer each of his questions (this is the 5th and final). You can find my answers to other sets of questions, here, here, here, and here. Here’s a link to Jonathan’s original Part 5 post and the other poets’ answers: 5 Questions for Poets.

And here are my answers:

1. How hard should you work at a poem?

As hard as it takes to get the poem where it wants to go and get the author out of the way.

2. According to The Atlantic, over 50 percent of people think computers will be able to write great works of literature in 50 years. Do you hold with the majority prognostication?

Great works of literature? I doubt it. But then, when artificial intelligence takes over, great will be defined by a different standard.

3. What would poets like for undergrads to know about poetry?

Poems are pleasure, as Donald Hall wrote in “The Unsayable Said: an essay,” “Poems are pleasure first, bodily pleasure, a deliciousness of the senses. Mostly, poems end by saying something (even the unsayable) but they start as the body’s joy, like making love.” I think if students had this in mind — maybe a few teachers too — poetry would be better taught and more widely read.

4. What interests outside of literature work well with writing poetry?

Many and various interests outside literature work well with poetry, sports, romance, hiking, travel, even work. I found my work with The Nature Conservancy exposed me to so many of nature’s wonders and details that it proved a storehouse of inspiration for my poetry. But even now, when I work for a Big Four firm’s cleantech practice, I’m in one of my most productive periods. It’s all about paying attention.

5. If you were poet during a different era, when/where would you want to exist?

In a workshop long ago Gary Snyder accused me of having a 17th or 18th century sensibility as a poet. So, maybe that’s where I’d find a home. But I’m very happy where I am right here and now.

Yet More 5 Questions for Poets

June 4, 2014

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

I’m going to continue to answer these questions (this is Part 3 for me, but out of sequence with the original; you can find my answers to other sets of questions, here, here, and here). Here’s a link to Jonathan’s original Part 4 post and the other poets’ answers: 5 Questions for Poets.

And here are my answers:

1. April 23 was Shakespeare’s 450th anniversary. If you went back in time and could ask him one question, what would that question be?

How the hell did you do it?

2. What bothers you most in your literature community?

That I don’t get to spend more time in it – whether it’s my virtual community “52” or the one where I live in Brooklyn. There are some wonderful poets – wonderful people! – in those communities and I really wish I had more time to hang out with them. In the larger poetry community: careerism, cronysism, and churlishness.

3. Which poets, alive or dead, are overrated/underrated?

I’m sure I’ll offend with this comment but I find Charles Bukowski completely overrated and over-read. And his influence is dreadfully felt. Among contemporaries, I also can’t see what all the fuss is about Dorothea Lasky, there doesn’t seem to be much there there. (I can see the email daggers massing in my in-box or, for that one.)

There are way too many underrated contemporary poets to mention them all, but among the dead Lorine Niedecker, Kenneth Patchen, and Walter Pavlich have always seemed unfairly neglected in my book.

4. Are prizes like Pulitzer, NBA, NBCC are good for poetry. Is there discrimination against women poets, non-white poets, gay poets?

Prizes are for poets, not poetry. It seems like a popularity contest more than anything. I’m sure there is discrimination; you find that wherever there are human beings, cliques, factions, and dominant cultural hierarchies. Others have VIDA stats and ratios to prove it.

5. Is poetry useful?

Poetry is neither as useful as a tool nor as useless as a whim. Of course, I couldn’t live without it.

Still More 5 Questions for Poets

May 15, 2014

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

I’m going to continue to answer these questions (this is Part 3 for me, but out of sequence with the original; you can find my answers to other sets of questions, here and here). Here’s a link to Jonathan’s original Part 2 post and the other poets’ answers: 5 Questions for Poets.

And here are my answers:

1. What qualities or subject matter do you feel is missing in contemporary poetry?

In my humble opinion, there are four things lacking in contemporary (American) poetry: 1.) a sense of the history of poetry before Bukowski and the Beats; 2.) a belief that there are ANY universal truths; 3.) faith in the power of love; and 4.) thinking, deep and critical. Individual poets fill this void, to be sure, but generally speaking, the poetry that gets attention these days seems lacking in many ways.

2. What is your writing and editing process like? How long does it generally take you to finish a poem?

If asked that a year or two ago I would have said, I work late at night, usually while walking, and work on poems a lot in my head before I get anything on paper. When I do get a poem on paper it is long-hand first, then I type it up. Then I revise, revise, revise, until the poem goes where it wants to go.

Lately, however, I’ve completely changed my way of working. In part, because of two experiences: last year I wrote a poem-a -day for National Poetry Month and posted it on my blog: raw, unedited, and “unfinished.” (I’ve since gone over them a bit, but the originals are still up for all to see.)

Then, this year, I joined a poetry group started by Jo Bell in the UK. The group is called “52” and meets virtually, in a closed group on Facebook. It’s called 52 because the challenge is to write a poem a week in response to a prompt posted each Thursday. It’s been remarkably fruitful. Will anything survive the experiment? I already have 2-3 poems I feel are worth continuing to work on, and a few others that served their purpose as occasional verse.

The result is I’m writing quickly, much more quickly than my previous, more methodical efforts, and usually on my iPhone. Is it a better way of working? Only time will tell.

3. What Poets Do You Read?

I read any and all poetry I can get my hands on. I try to buy a handful of poetry books each year – I need to contribute to the poetry economy and, if I’m going to ask others to buy my books, I should support other poets. Most recently, I’ve bought and read collections by Jo Bell, Kathleen Jamie, John Glenday, Ada Limon, Ethan Paquin, Don Paterson, Jo Shapcott, and Robert Wrigley. And I’ve been reading a lot of Tamil poetry, in translation of course, both modern and classical.

I’ve also read Alfred Corn’s last collection, Tables, and thoroughly enjoyed reconnecting with his work this year. I went back to Seamus Heaney’s poetry when he died last summer; such remarkable language and imagery. Jack Gilbert’s Collected Poems, which my mother-in-law gave me for the holidays last year, is still on my bedside table and I dip into it as often as possible. Frederick Seidel captured my attention two years ago. It took me an entire year to get through his Selected Poems, 1959-2009, but it was worth it. He’s a trip.

And, of course, Elizabeth Bishop remains a constant for me. I turn most often to her work.

4. What is an up-and-coming poet?

An up-and-coming poet, I guess by that you mean an emerging poet? It’s funny, when I won the Nebraska Review and Aldrich Emerging Poets awards back in the late 90s, I thought, “Okay, so I’m emerging, now what?” It took 15 more years for my book, FALLOW FIELD, to come out. Am I still emerging? Have I emerged? Am I up-and-coming? I’m glad to be up at all, frankly; as they say, the alternative is much worse.

5. Who is the best living poet?

Up until he died at the end of last summer, I would have said Seamus Heaney.

If by “best” you mean “greatest living,” I’d have to say Derek Walcott, at least in terms of the scope and breadth of his work. There is a real sense of history in his poetry. It is rich and full of traditions and truths that are both global and place-based. His thinking is deep and critical, and his poetry is full of faith in love. Take his “Love After Love”:

The time will come

when, with elation

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror

and each will smile at the other’s welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.

–Derek Walcott

5 More Questions for Poets

May 6, 2014

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrated National Poetry Month by posing “5 Questions for Poets” by readers of poetry.

I’m going to continue to answer these questions (this is Part 2 for me, but out of sequence with the original; you can find my answers to Part 1, here). Here’s a link to Jonathan’s original post and the poets’ answers: 5 Questions for Poets, Part 3.

And here are my answers:

- How many of your poems do you throw away?

I believe, as Paul Valery wrote, “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.” I never throw them away. Sometimes I find lines that are useful elsewhere or I work on them and find a way to let them get where they need to go over a period of years.

Of course, there are many, many that will never find their way and will never see the light of day. I want only those poems that I have “finished” or “abandoned” to represent my work in the world. I’ll be lucky if even one or two survive beyond my lifetime.

- Do you still get poems rejected in poetry journals?

All the time. The ones that hurt the most are the seemingly annual rejections from The New Yorker, POETRY, Ploughshares, The Gettysburg Review, all places where I really want to publish someday, but others as well. I try to move on quickly and send them out again. If a poem gets rejected more than a few times, I’ll pull it out of circulation and take another look at it. I’ve been fortunate to be published in some very fine places, in print and online.

- How many poems do you have memorized?

Only one, I think. “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop. Oh, and parts of others. I was never good at memorization. I have too much poetry working in my head and my filing system is only big enough for what I’m working on. Although, I did recite Whitman’s “O Captain, My Captain,” when I was nine.

- Are creative writing programs good or bad for literature? Why?

Good and bad. At its best, a creative writing program will encourage writers to hone their craft and voice, to improve their work through revision and paying attention to what a poem needs. At worst, it is a breeding ground for poetry careerism and cronyism and mimicry of the worst sort.

Of course, when I asked Robert Hass whether I should get an MFA, he, in turn, asked me, “Do you want to teach?” I cheekily answered, “No, I don’t think you can teach writing poetry.” He told me to go out and get a real job, to experience life and have something to write about other than academic life, and that has made all the difference to me.

- Do you think the Best of American Poetry, or Best Poems of 20__ and the Pushcart annual are useful indices of the best work now being published?

Obviously not, they’ve never included any of mine – not even some of my better efforts, like “Naming” and “Fallow Field.” The latter was nominated for a Pushcart, but as the title poem of my collection published last fall, not in the year it was published in Blueline.

In all seriousness, these lists or time-sensitive anthologies represent the opinion, taste or whims of an individual or a series of individuals; the editor of the anthology, etc, and those who chose the poems for publication in the first place. Nothing more; nothing less.

5 Questions for Poets

April 2, 2014

Jonathan Hobratsch, writing in the Huffington Post, celebrates National Poetry Month by posing 5 questions by readers of poetry to some of the “top poets” writing today. Alfred Corn posted the questions to his friends on Facebook.

Here are my answers:

1. Do the Internet and social media contribute to the well-being of poetry?

On the plus side, my work has reached audiences beyond the reach of traditional publishing venues, and I’ve met and been exposed to poets from around the world whose work I could not have otherwise found. My community of poets has grown and challenged my work in new and fascinating ways.

2. What do most poorly-written poems have in common?

Language or structure that doesn’t serve the poem. Over-writing or lazy writing. Sentimentality. Lack of music. Basically, when it’s clear the poet hasn’t listened to the poem.

3. What do most well-written poems have in common?

They sing. They make you dance. And they give you a new way of looking at the world.

4. How important is accessibility of meaning? Should one have to work hard to “solve” the poem?

Poetry should be neither a Rubik’s cube nor a road sign.

5. What book are you reading right now?

All Standing: The Remarkable Story of the Jeanie Johnston, the Legendary Irish Famine Ship by Kathryn Miles; The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot by Robert McFarlane; Orr: My Story by Bobby Orr; and Navigation by Jo Bell.

Here’s a link to the original article: 5 Questions for Poets

Seamus Heaney Remembered

November 12, 2013

A stellar lineup of poets, musicians, publishers, and poetry organizations gathered last night to pay tribute to Seamus Heaney.

Heaney, the 1995 Nobel laureate in literature, died after a fall on Friday, August 30, 2013, in Dublin. He had suffered a stroke in 2006.

The event, organized by the Poetry Society of America, the Academy of American Poets, Poets House, the Unterberg Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y, the Irish Arts Center PoetryFest, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Heaney’s US publisher, took place at the Great Hall of Cooper Union in New York City, an appropriate venue for such a stentorian public poetic figure.

Among the readers were Heaney’s fellow Irish poets Eamon Greenan, Eavan Boland, Greg Delanty, and Paul Muldoon, along with Tracy K. Smith, Kevin Young, Jane Hirshfield, and Yusef Komunyakaa. You can read the full list here: Heaney Tribute.

One poem that was missing last night was one that I thought of shortly after hearing the news of Heaney’s death.

We were heading out to Martha’s Vineyard for a week with Samantha’s family to celebrate the 70th year of her mother, Lee Langbaum. The New York Times the morning we left had Heaney’s picture on the front page and ran his obituary, but I couldn’t get to it until much later in the day, aboard the ferry.

It was sad news indeed, for those of us who loved his poetry and for the world that lost a remarkable voice. Heaney was a wonderful poet and a warmhearted man, as most of the people gathered at Cooper Union last night — whether on stage or off — would attest.

I only met him twice, and only very briefly after readings, but he was gracious and generous both times. The last time I saw him was at a reading three years ago or so at Villanova University.

The poem that came to mind on Martha’s Vineyard, came to me as we were talking with the oyster shucker outside of Home Port Restaurant in Menemsha. Of course it was “Oysters,” a poem that was missing last night.

Here is Seamus Heaney’s “Oysters”:

Our shells clacked on the plates.

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades

Orion dipped his foot into the water.

Alive and violated,

They lay on their bed of ice:

Bivalves: the split bulb

And philandering sigh of ocean —

Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered.

We had driven to that coast

Through flowers and limestone

And there we were, toasting friendship,

Laying down a perfect memory

In the cool of thatch and crockery.

Over the Alps, packed deep in hay and snow,

The Romans hauled their oysters south of Rome:

I saw damp panniers disgorge

The frond-lipped, brine-stung

Glut of privilege

And was angry that my trust could not repose

In the clear light, like poetry or freedom

Leaning in from sea. I ate the day

Deliberately, that its tang

Might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

—Seamus Heaney, 1939-2013

Here is Heaney reading his poem at the Griffin Poetry Prize Awards ceremony in 2012: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xslwsp_seamus-heaney-oysters_creation

Next month marks the bicentennial of Robert Browning, who was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. My Samantha recently sent me his poem “Now” and it spoke to me, although it was not familiar to me.

Browning is a bit of an enigma: simultaneously overshadowed by his more famous wife, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and lionized as one of the great creators of the dramatic monologue.

Victorian readers found his work somewhat difficult, in part because of his sometimes arcane language and obscure references. He was home-schooled and self-taught – subsequently, many of his allusions were lost on his more conventionally educated audience.

Ultimately, Browning, as Wordsworth said of all great poets, had to “create the taste by which [he was] to be enjoyed.”

One of Browning’s enduring themes was “ideal love,” which for the poet meant the consummation and culmination of an intuitive course of action wherein a pair of lovers pierce the barrier separating them to become one in an all-consuming spiritual union — the “moment eternal” between two human beings.

To Browning, the passion and intensity of romantic love was often at odds with conventional social morality. Ideal love in Browning’s conception required giving up everything, what others have called “the world well-lost for love.”

Here is Robert Browning’s short lyric poem, “Now”:

Out of your whole life give but a moment!

All of your life that has gone before,

All to come after it, — so you ignore,

So you make perfect the present, condense,

In a rapture of rage, for perfection’s endowment,

Thought and feeling and soul and sense,

Merged in a moment which gives me at last

You around me for once, you beneath me, above me —

Me, sure that, despite of time future, time past,

This tick of life-time’s one moment you love me!

How long such suspension may linger? Ah, Sweet,

The moment eternal — just that and no more —

When ecstasy’s utmost we clutch at the core,

While cheeks burn, arms open, eyes shut, and lips meet!

–Robert Browning, 1812-1889

Visions Coinciding: Celebrating Elizabeth Bishop’s Centenary

December 5, 2011

As readers of this blog know, 2011 marks the centenary of Elizabeth Bishop’s birth. I’ve been trying to celebrate it in as many ways as possible and get to some of the events throughout the year, as well as visiting her grave in Worcester, MA, and promoting her work on this blog and on Twitter by using #EB100.

Last week I attended Visions Coinciding: An Elizabeth Bishop Centennial Conference, organized by NYU’s Gallatin School and the Poetry Society of America.

The conference featured interdisciplinary responses to Bishop and her work, including a slide show and talk by Eric Karpeles exploring rarely seen images of Elizabeth Bishop and a screening of footage from Helena Blaker’s forthcoming documentary on Bishop’s years in Brazil.

The screening was followed by a discussion moderated by Alice Quinn, editor of Bishop’s posthumous collection Edgar Allen Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments, along with Blaker and Bishop scholars Brett Millier, Barbara Page, and Lloyd Schwartz.

Day two featured two lectures on Bishop’s relationship with Art. Peggy Samuels gave a fascinating exegesis of Bishop’s interest in and influence by the work of Kurt Schwitters and William Benton displayed slides of Bishop’s own paintings, sharing his insights on their context in modern art.

Jonathan Galassi moderated a lively discussion with the editors of recent collections of Bishop’s poetry, prose and correspondence, including Joelle Biele (Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker correspondence), Saskia Hamilton (Words In Air

, the Lowell-Bishop correspondence, and new edition of POEMS

), Lloyd Schwartz (new edition of PROSE

, as well as the Library of America edition of Bishop: Poems, Prose, Letters

), and Thomas Travisano (Lowell-Bishop correspondence).

All this was followed by a reading by NYU Gallatin students who each read a Bishop poem and one of their own by way of response and, finally, a star-studded lineup of contemporary American poets, including John Koethe, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Mark Strand reading poems by Bishop.

Poet Jean Valentine read Bishop’s translation of Octavio Paz’s “Objects & Apparitions” with the original read by Patrick Rosal. Maureen McLane read from her creative work-in-progress “My Elizabeth Bishop; My Gertrude Stein.”

This week is the opening of Elizabeth Bishop: Objects & Apparitions at the Tibor De Nagy Gallery in New York. The show comprises rarely exhibited original works by Bishop, including watercolors and gouaches, as well as two box assemblages inspired by the work of Joseph Cornell.

The exhibition also includes the landscape painting Miss Bishop inherited and that she wrote about in “Poem,” which begins

About the size of an old-style dollar bill,

American or Canadian,

mostly the same whites, gray greens, and steel grays

-this little painting (a sketch for a larger one?)

has never earned any money in its life.

Unfortunately, I’m going to miss the exhibit of her papers at the Vassar College Main Library, From the Archive: Discovering Elizabeth Bishop, which is on view until December 15th.

But there’s still time to celebrate Bishop’s centenary — until her 101st on February 8, 2012.