My Year in Writing 2023

December 6, 2023

Now is the time, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing. This year, which culminated my sixtieth trip around the Sun, has been a pretty productive year.

Here are some of the highlights:

Barzakh Magazine accepts essay, “Açorianidade & the Radiance of Sensibility” just after Xmas! (Published in January)

Reading of Berkshire Writers in Housatonic; read the first chapter of Falling Up. (January)

Guest writer @ Margarida Vale de Gato’s Eco-poetics Masters Class, Universidade de Lisboa via Zoom (January)

Alfred Lewis Bilingual Reading Series, FresnoState PBBI(part of the PBBI-FLAD lecture series 2023), Co-curators: Diniz Borges and RoseAngelina Baptista; Poets: Alberto Pereira, Sam Pereira, PaulA Neves, Scott Edward Anderson, and RoseAngelina Baptista (February)

Guest lecturer, Universidade de Lisboa, Professora Margarida Vale de Gatos’ class on American Literature in person. (March)

Guest speaker, Universidade dos Açores, Ponta Delgada, Professora Ana Cristina Gil’s class, in person. (March)

My essay, “STUDIO LOG: THE TOM TOM CLUB’S “GENIUS OF LOVE,” A MEMOIR AND EXPOSITION IN 18 TRACKS,” lost in the 2nd Round of the Marchxness battle of “One Hit Wonders” to Adam O. Davis’ essay on “In a Big Country” by Big Country. (March)

Installation of my poem. “River of Stars,” on Poetry Path at Ryan Observatory at Muddy Run, and presentation with Michele Beyer (a teacher inspired by my conversation with Derek Pitts in November 2022) to write poetry with her class. (April)

Interview by Francisco Cota Fagundes published in Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-American Letters and Studies, XLVII, as part of a special issue devoted to Celebrating Portuguese Diaspora Literature in North America. (Spring)

Guest lecturer, University of California at Santa Barbara, Portuguese literature class, Professor André Corrêa de Sá. (June)

“Love & Patience on Mt. Pico” (essay) published in The Write Launch (July)

“Through the Gates of My Ancestral Island” (essay) published in Panorama: The Journal of Travel, Place, and Nature (July)

“Orpheu Ascending,” a review of Orpheu Literary Quarterly, volumes 1 and 2, translated from the Portuguese by David Swartz, published in Pessoa Plural—A Journal of Fernando Pessoa Studies, Issue 23 (July)

Seeing—Reading—Writing: Transforming Our Relationship to Language and Nature: A Workshop with Ryan Shea and Scott Edward Anderson at The Nature Institute, Ghent, NY (July)

Creative nonfiction mentor, Adroit Journal Summer Mentorship Program, mentored two students. (July)

“Birds in the Hand: The Berkshire Bird Observatory’s Impassioned Ben Nickley” (article) in Berkshire Magazine. (July)

Poetry booth, “Zucchrostic poems,” at West Stockbridge, MA, Zucchini Festival (August)

Two poems in Into the Azorean Sea: A Bilingual Anthology of Azorean Poetry, translated and organized by Diniz Borges, published by Letras Lavadas in São Miguel and Bruma Publications, Fresno State. (August)

Meet & Greet at The Book Loft in Great Barrington, MA. (Sept)

“Berkshire Brain Gain” (article) published in Berkshire Magazine (Sept)

Dedication of Binocular telescope at Ryan Observatory at Muddy Run and poems by Ada Limón and Gabe Catherman installed on Poetry Path. (October)

Visited Praia da Vitória on Terceira Island, Azores, birthplace and boyhood home of Vitorino Nemésio. (October)

Participated in Arquipélago de Escritores in Angra on Terceira Island. (October)

Met António Manuel Melo Sousa in Ponta Delgada with Pedro Almeida Maia (see related entry below) (October)

Guest lecturer, Fresno State, Professor Diniz Borges’ class on Azorean Literature, presented “Becoming Azorean American: A Diasporic Journey,” (lecture). (October)

“António Melo Sousa, Letras de canções e outros rascunhos – uma apreciação” (review) published in Grotta: Arquipélago de Escritores, #6. (November)

Recorded an episode of “Solo Creatives of the Berkshires” for CTSB-TV, Community Television for the Southern Berkshires, presenting and reading from several of my books. (November)

“Get ‘Hygge’ With It: Cozy Spots and Comfort Food in the Berkshires” (article) published in Berkshire Magazine. (December)

“Seeking My Roots Through a Painter’s Eyes” (essay) published in Revista Islenha, Issue 73, in Madeira, Portugal. (December)

Habitar: um ecopoema, Margarida Vale de Gato’s translation of my book, Dwelling: an ecopoem, gets mention in Paula Perfeito’s Entre-Vistas blog. (27 December)

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.”

Like I said last year, I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

My Year in Writing: 2022

November 28, 2022

Now is the time, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing. It’s been a pretty productive year, considering it also included a move from Brooklyn to the Berkshires:

Published Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations (Shanti Arts)

Book launch for Wine-Dark Sea online with Kathryn Miles (Feb)

Appearance on Portuguese American Radio Hour with Diniz Borges (March)

World Poetry Day/Cagarro Colloquium reading (March)

Book launch with Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (March)

Book signing at Terrain.org booth at #AWP22 in Philadelphia (March)

Wine-Dark Sea gets “Taylored” by @taylorswift_as_books on Instagram! (March)

Lecture at University of the Azores: Mesa-redonda Poesia, Tradução e Memória (April)

Azores launch for Wine-dark Sea and Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana at Letras Levadas in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, Azores, with Leonor Sampaio Silva (April)

Açores Hoje television interview with Juliana Lopes on RTP Açores (April)

Terrain.org Reading Series with Joe Wilkins and Betsy Aoki (April)

“Phase Change” and “Under the Linden’s Spell” reprinted in TS Poetry’s Every Day Poems (online/email)

“Midnight Sun” and “Shapeshifting” reprinted in Earth Song: a nature poems experience (anthology), edited by Sara Barkat and published by TS Poetry Press

Named Ryan Observatory’s first Poet Laureate

Mentored 2 students in Creative Nonfiction for Adroit Journal Summer Mentorship Program (June/July) [UPDATE: one of the students I mentored got accepted into the University of Pennsylvania, early decision! So proud of her!]

Translated Pedro da Silveira’s A ilha e o mundo, his first book of poems (1952)

Excerpts from Corsair of the Islands, my translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s Corsário das Ilhas, published in Barzakh Magazine (online) (August)

Panelist/presenter at Colóquio: Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedo cultural, University of the Açores: On Translating Pedro da Silveira’s A Ilha (September)

Lançamento da obra Habitar: um ecopoema, Margarida Vale de Gato’s translation of Dwelling: an ecopoem, published by Poética Edições, with Nuno Júdice, Luís Filipe Sarmento, and Margarida Vale de Gato, at FLAD in Lisbon (September)

Guest lecturer in Creative Writing at University of the Azores (Leonor Sampaio Silva, professora)

Panelist/presenter at 36th Colóquio da Lusofonia, Centro Natália Correia, Fajã de Biaxo, São Miguel, Azores: reading from Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana with Eduardo Bettencourt Pinto (October)

#YeahYouWrite Catskill Reading at Fahrenheit 451 House, Catskill, NY w/Stephanie Barber, Laurie Stone, and Sara Lippmann (October)

Guest Writer at UConn Stamford creative writing class (Mary Newell, professor) (October)

Poet & Astronomer in Conversation (with Derrick Pitts, Chief Astronomer of the Franklin Institute) at Ryan Observatory at Muddy Run, PA (November)

“Wine-Dark Sea” (poem) published in American Studies Over_Seas (November)

20th Anniversary of residency at Millay Arts and writing of Dwelling: an ecopoem (November) [UPDATE: Got asked to join the Board of Millay Arts in December.]

Selections from Habitar: um ecopoema published in Gávea-Brown (US) and Grotta (Azores)

Book reviews in Gávea-Brown and Pessoa Plural [Postponed until 2023.](December)

My essay, “Açorianidade and the Radiance of Sensibility,” accepted by Barzakh Magazine for publication in Winter 2023 issue. (December)

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.”

Like I said last year, I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

WINE-DARK SEA BOOK LAUNCH & READING

March 2, 2022

In conversation with Kathryn Miles

On #pubday eve, Kathryn Miles and I got together to chat about my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. We had a wide-ranging conversation about the book, specific poems, finding love at middle age, the idea of home, and the Azores — and I even read a poem in Portuguese.

Have a look here:

The book came out March 1st and is available through the links on my website: scottedwardanderson.com/wine-dark-sea

My Year in Writing: 2021

November 24, 2021

Now is the time of year, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing.

What a year it’s been, deepening my connections to my ancestral homeland of the Azores, as well as my ties to the diaspora throughout North America. Here we go:

- Signed contract with Shanti Arts for Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations to be published in Spring 2022. (Technically signed this at the very end of 2020, but thought it was worth mentioning again.)

- Published “Five Poems by Vitorino Nemésio” in my English translations in Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies.

- Interview and review by Esmeralda Cabral appeared in Gávea-Brown and was later translated into Portuguese by Esmeralda and Marta Cowling and appeared in Diário dos Açores.

- Published four translations by Margarida Vale de Gato from Dwelling in Colóquio/Letras by the Gulbenkian Foundation. And signed contract with Poética Edições for Habitar: uma ecopoema, translation by Margarida of my book Dwelling: an ecopoem. Received funding for Margarida’s translation from FLAD.

- Associação dos Emigrantes Açorianos AEA video presentation, “Açores de Mil Ilhas” for World Poetry Day.

- Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana review by Maria João Covas (video); and translation of Vamberto Freitas’s (2020) review published in Portuguese-American Journal.

- Wrote a poem in português for Letras Lavadas’s celebration, Dia Internacional da Mulher. Here is the video presentation, which includes the fabulous Aníbal Pires reading my poem, “A outra metade do céu/The other half of the sky.”

- Talk for New Bedford Whaling Museum on “Azorean Suite: A Voyage of Discovery Through Ancestry, Whaling, and Other Atlantic Crossings”

- Dwelling featured in a class at Providence College on Environmental Philosophy, thanks to Professor Ryan Shea; spent a week there, including teaching three classes and giving a reading/talk at the PC Humanities Forum.

- Readings: RONDA: Leiria Poetry Festival (March); Filaments of Atlantic Heritage (March), Cravos Vermelhos Oara Todos os Povos/World Poetry Movement Reading (April); A Nova Revolução dos Cravos (April), Cagarro Colloquium—Azores Day & launch (May); ASLE Spotlight Series (June); Juniper Moon’s Sunday Live reading series (August), LAEF Conference/PBBI (October); and A Voz dos Avós Conference/PBBI (November). Phew, I’m exhausted just writing that schedule!

- Translated poems by Luís Filipe Sarmento, Ângela de Almeida, and Adelaide Freitas.

- Panelist for PALCUS on Embracing Modern Portuguese Culture (spoke about Cagarro Colloquium, translation, etc.).

- Participated in “Insularity and Beyond: The Azores & American Ties” webinar with University of the Açores.

- Participated in session with Margarida Vale de Gota’s translation students at University of the Lisbon via Zoom.

- Recorded a video—em português—for Letras Lavadas’s second anniversary of bookstore in PDL

- Finished a draft of my translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s Corsário das Ilhas and revisions corresponding to new (2021) Portuguese edition.

- Published my talk from PC Humanities Forum in Gavéa-Brown.

- Published “Wine-Dark Sea” (poem) in America Studies Over_Seas.

- Published two poems, “The Pre-dawn Song of the Pearly-eyed Thrasher” and “Under the Linden’s Spell,” in The Wayfarer.

- Published “Phase Change” (poem) in ONE ART (online poetry journal).

- Scrapped portions of my work-in-progress, The Others in Me, after consulting with two writer friends about it, but found a new approach through working with Marion Roach Smith, which I will start in 2022…

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.” I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

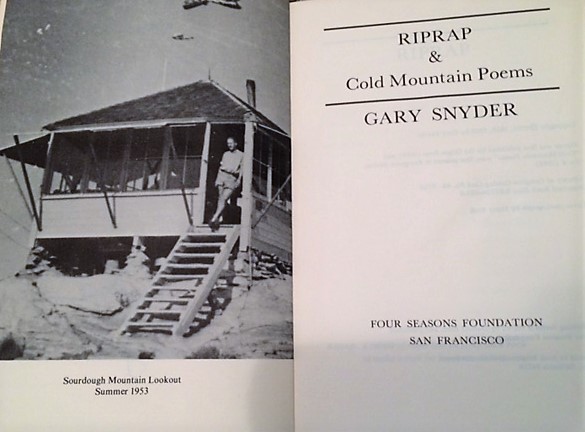

The author’s copy of Riprap & Cold Mountain Poems by Gary Snyder.

Schuykill Valley Journal Online published my essay on Gary Snyder’s “Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout” last month. Here are the introductory paragraphs and a link to the full essay:

To get to Sourdough Mountain Lookout, you hike a good five miles, gaining 5000 feet or more of elevation. The terrain is rugged and the hiking strenuous, but that’s to be expected in the Northern Cascades. Located 130 miles northeast of Seattle, Washington, the Forest Service opened one of its first lookouts here in 1915.

The view from the lookout station, constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, is a postcard in every direction: Hozomeen Mountain and Desolation Peak looking north, Jack and Crater mountains out east, Pyramid and Colonial peaks to the south with Ross and Diablo lakes directly below, and, as if not to be outdone, the Picket Range is off to the west. This is impressive country and you can understand why it’s been an inspiration to poets and writers for generations.

Poet Gary Snyder was 23 when he worked as a fire-spotter on Sourdough Mountain in 1953.

David Simpson reading at NYU CEnter for Creative Writing in December 2014, while his brother Dan records.

I’ve known David Simpson for a dozen years, probably more. We were introduced by another writer in Philadelphia and became fast friends, sharing poems with each other, giving readings together on stages and coffee houses.

Dave was funny, direct, and touching in ways that few other poets were in those days. I mean without being solipsistic or confessional or glib or “clever.”

His work reminded me more of Gerald Stern, David Ignatow, or Frank O’Hara than that of any of his contemporaries. I admired a certain casual freedom he offered in his work.

When Dave, who along with his twin brother, poet Dan Simpson, is blind, contracted ALS recently, it seemed unfair. Here was this most gentle soul, funny and sometimes acerbic, always caring for others, stricken by a crippling and debilitating disease.

Dave and I both agonized over our collections of poetry – for years — and the length of time it took us to compile and find a publisher. Both outsiders in the “poetry biz” world, we had time to refine our collections, sharing poems and encouraging each other – even competing with and inspiring each other.

With the publication of his book, The Way Love Comes to Me, just a few months after my Fallow Field, I was ready to celebrate with Dave. It had been a few years since we’d seen each other, as life changes, moves, and other circumstances would have it. So when Dave read at NYU this past winter, I leapt at the chance to go see him, congratulate him, and hear him read again.

I wasn’t disappointed. Even though I could see he was suffering and the disease was clearly getting the upper hand in the battle, Dave remained the same hopeful, witty, entertaining, thoughtful person I’ve always known.

Yet, as his brother Dan wrote in a recent blog post, “ALS, like other terminal illnesses, forces you to redefine what you mean when you use words like ‘good’ and ‘hope.’ Dave says he can see losses every week. He no longer hopes to perform his one-man show. His idea of a good day has more to do with breathing well, with the help of his by-pap machine, and reading something stimulating than with treks into the city and hosting dinners for friends and family.”

At readings, his poem “Spring Fever,” was always a crowd-pleaser. It’s Dave’s “big hit.” He had to read it or his fans would clamor for it. He probably grew sick of reading it, not wanting to be a one-hit wonder.

When he read it at NYU in December, I immediately wanted to share it with my readers during National Poetry Month this year. Why? Because it has all those qualities I love in Dave and his poetry: humor, pathos, and a beautiful way of rendering tenderness in human interactions.

Here is David Simpson’s poem, “Spring Fever”:

A basketball bounces by the pharmacy as I go in.

Thin music from speakers overhead

mixes with the almost-B-flat hum of neon lights. A cashier,

seeing I am blind, locks her register,

grabs a basket, and leads me by the hand down narrow aisles

as we discuss best buys

on Colgate toothpaste with fluoride,

unscented stick deodorants, and three-roll packs

of two-ply toilet paper. In my ears,

my blood begins to prod: Condoms…condoms

and I say to her: “I need

batteries–four double A’s”

Condomscondomscondoms

“and then, let’s check out the condom display.”

She stands on tiptoes to take down

the box of twelve Latex nonoxynol 9’s,

dips low to read me others that advertise

ribs and dimples, or flavors of mint

and mandarin. “Don’t get the mandarin,” she advises,

her hair brushing my hand as she stands up.

The brand name Excita makes us laugh a little

and I get to talking about Ramses and all his offspring

and what kind of confidence would a name like that

instill in someone looking for birth control?

To nearby customers, it might seem as if

we’re lovers, or very married. I wonder if she…

if we… I choose a pack of Lifestyles; she

puts them in the basket, and for just

a moment before we move

toward the checkout line, they are ours.

c) David Simpson

Used by permission of the author.

PS You can order Dave’s book — and I encourage you to do so — on Amazon.

I didn’t really know Jack Gilbert’s poetry much before my partner, Samantha’s mother (and my friend), Lee Langbaum, gave me his Collected Poems for the holidays, shortly after the poet’s death. (Gilbert died last November, after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.)

I didn’t really know Jack Gilbert’s poetry much before my partner, Samantha’s mother (and my friend), Lee Langbaum, gave me his Collected Poems for the holidays, shortly after the poet’s death. (Gilbert died last November, after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.)My life has been enriched reading Gilbert’s poetry — at times acerbic, quirky, and irascible — but I need to take him in small doses. There’s a risk in getting too close to fire.

Emily Dickinson famously wrote that “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.”

Jack Gilbert’s poetry approaches that more often than not.

“He takes himself away to a place more inward than is safe to go,” the poet and novelist James Dickey said of Gilbert. “From that awful silence and tightening, he returns to us poems of savage compassion.”

“The hard part for me is to find the poem—a poem that matters,” Gilbert told The Paris Review. “To find what the poem knows that’s special. I may think of writing about the same thing that everyone does, but I really like to write a poem that hasn’t been written. And I don’t mean its shape. I want to experience or discover ways of feeling that are fresh. I love it when I have perceived something fresh about being human and being happy.”

Here is Jack Gilbert’s poem, “The Forgotten Dialect of the Heart”:

How astonishing it is that language can almost mean,

and frightening that it does not quite. Love, we say,

God, we say, Rome and Michiko, we write, and the words

Get it wrong. We say bread and it means according

to which nation. French has no word for home,

and we have no word for strict pleasure. A people

in northern India is dying out because their ancient

tongue has no words for endearment. I dream of lost

vocabularies that might express some of what

we no longer can. Maybe the Etruscan texts would

finally explain why the couples on their tombs

are smiling. And maybe not. When the thousands

of mysterious Sumerian tablets were translated,

they seemed to be business records. But what if they

are poems or psalms? My joy is the same as twelve

Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light.

O Lord, thou art slabs of salt and ingots of copper,

as grand as ripe barley lithe under the wind’s labor.

Her breasts are six white oxen loaded with bolts

of long-fibered Egyptian cotton. My love is a hundred

pitchers of honey. Shiploads of thuya are what

my body wants to say to your body. Giraffes are this

desire in the dark. Perhaps the spiral Minoan script

is not a language but a map. What we feel most has

no name but amber, archers, cinnamon, horses and birds.

-From THE GREAT FIRES: POEMS, 1982-1992 (Alfred A.Knopf, 1994)

Here is an audio recording of Gilbert reading this poem on April 12, 2005 at The New School in New York: http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/19351

Elegy & Exile: Elizabeth Bishop’s Poem “Crusoe in England”

February 8, 2012

All year long I’ve been celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of the poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979).

You can read some of what I’ve written about Ms. Bishop and her poetry on this blog.

Today, the 101st anniversary of the poet’s birth, to mark the completion of the centennial celebrations, I want to share my essay “Elegy & Exile: Elizabeth Bishop’s Poem ‘Crusoe in England’.”

Here is my essay as it appeared in The Worcester Review‘s special edition “Bishop’s Century: Her Poems and Art”:

A new volcano has erupted,

the papers say, and last week I was reading

where some ship saw an island being born

…

They named it. But my poor island’s still

un-rediscovered, un-renamable.— Elizabeth Bishop

So begins Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, “Crusoe in England” one of two fine elegies found in her last collection, Geography III, and her longest sustained narrative poem.

The island is “un-renamable,” which implies it was named by someone once. In fact, the speaker in the poem named it “The Island of Despair,” for its volcanic centerpiece, “Mont d’Espoir or Mount Despair.” He had time to play with names; twenty-eight years, by at least one account.

The speaker is, of course, the protagonist of Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel, Robinson Crusoe – and he isn’t.

Defoe’s Robinson was Christian, civilized, and strongly empirical in his thinking; Bishop’s Crusoe is skeptical and unsure of his knowledge and memory.

Both are displaced figures, but Defoe’s Robinson feels that displacement most acutely on the island upon which he is shipwrecked. Bishop’s Crusoe feels more displaced after his return to “another island,/ that doesn’t seem like one…” His home country of England.

Crusoe was lonely on the island; its clouds, volcanoes, and water-spouts were no consolation – “beautiful, yes, but not much company.” He experiences a “dislocation of physical scale,” as Bishop biographer Lorrie Goldensohn observed.

He’s a giant compared to the volcanoes, which appear in miniature from such distance; the goats and turtles, too. It is, Goldensohn writes, “an analogue of the nausea of connection and disconnection.”

Then “Friday” arrives, but even their relationship, in the Bishop poem, is tinged with loneliness. They both long for love they cannot consummate, “I wanted to propagate my kind,/ and so did he, I think, poor boy.”

Defoe’s Robinson is much less isolated. His island is visited by native cannibals who take their victims to the island to be eaten (Friday is their prisoner; until Crusoe saves him and names him), as well as Spaniards, and English mutineers. This last group helps Robinson return to England with Friday. There are other adventures in the novel, including a voyage to Lisbon and a crossing of the Pyrenees on foot.

None of this is for Bishop. Her goal was not to re-write the novel, but to re-imagine the story. Her Crusoe possesses, as C.K. Doreski has noted, “a weary tonality of such authenticity her character seems not an extension of Defoe’s fictional exile, but a real Crusoe, endowed with a twentieth-century emotional frankness.”

Bishop’s Crusoe finds even deeper loneliness back “home,” with its “uninteresting lumber.” Once there, he longs for the intensity of life on his island, its violence and self –determination, and its objects full of meaning.

“Disconcertingly,” as Goldensohn describes it, “Crusoe discovers that the misery from which he so willingly fled was the chief stock of his life.”

Defoe’s Robinson returns to England to find nothing there for him. Robinson’s family thought him dead after his 28-year absence, and there is no inheritance for him, no fortune to claim, no home.

Crusoe, in Bishop’s devising, also finds nothing for him at home, despite the longing he felt for it while a castaway. His loss is a spiritual and cultural loss.

While on the island, he tries to hold onto his home culture. He makes “tea” and a kind of fizzy fermented drink from berries he discovers, even a homemade flute with “the weirdest scale on earth.”

Alas, he doesn’t remember enough of his culture’s great literature to make him feel at home,

The books

I’d read were full of blanks;

the poems – well, I tried

reciting to my iris beds,

“They flash upon that inward eye,

which is the bliss…” The bliss of what?

One of the first things that I did

When I got back was look it up.

The bliss is, of course, “solitude,” which is the word completing this line from Wordsworth’s “Daffodils” (” I wandered lonely as a cloud…”). We forgive Bishop this anachronism; Wordsworth’s poem was written over one hundred years after Defoe’s novel. By referencing this line she creates a sense of displacement or dislocation in us, her readers.

For Bishop’s Crusoe, solitude approaches bliss by way of banality, especially when he reflects on what was lost – including Friday, who was introduced with the banal phrase, “Friday was nice and we were friends.”

The potency of their relationship is merely hinted at; perhaps reflecting Bishop’s own sense of decorum in matters personal. (“Accounts of that have everything all wrong,” Bishop writes.)

Some critics have suggested that Friday in this poem is a stand-in for Lota de Soares Macedo, Bishop’s Brazilian lover; while others, James Merrill among them, wondered why Bishop couldn’t give us “a bit more about Friday?”

For almost as soon as Friday arrives they are taken off the island. By the end of the poem, we learn that Friday died of measles while in England, presumably a disease to which he had no immunity.

Bishop began writing “Crusoe in England” in the early 1960s – although notebook entries from 1934 hint that the poem may have its origins in her time at Vassar – and picked it up again after Lota’s death in 1967. (Goldensohn postulates based upon her reading of drafts of the poem that Bishop brought Friday into the poem at that time.)

She worked on it again after a visit to Charles Darwin’s home in Kent. She relied on Darwin’s notes from the Galapagos for her depiction of the island, along with Herman Melville’s “Encantadas,” and perhaps Randall Jarrell’s “The Island,” as has been suggested, as well as on her own experience of tropical and sub-tropical locales.

By the time she visited Galapagos in 1971, however, the poem had been delivered to The New Yorker. She must have been fairly pleased that her description was almost spot-on. (My own experience of the Galapagos has the spitting and hissing she writes about coming from the iguanas rather than the turtles, but no matter.)

Bishop’s friend and fellow poet, Robert Lowell, thought “Crusoe” to be “maybe your very best poem,” and I’m inclined to agree. (Although the poem preceding it in 1979’s Geography III, “The Waiting Room,” gives it a run for my money.)

“An analogue to your life,”Lowell wrote in a letter to Bishop, “or an ‘Ode to Dejection.’ Nothing you’ve written has such a mix of humor and desperation.”

It’s true this poem has a kind of desperation to it that comes from desolation and longing, for “home,” in particular, be it the island or England. Bishop’s humor is evident, too, in such lines as

What’s wrong about self-pity, anyway?

With my legs dangling down familiarly

over a crater’s edge, I told myself

“pity should begin at home.” So the more

pity I felt, the more I felt at home.

“By making [Crusoe’s] life center around the idea of home,” writes biographer Brett Millier, Bishop “brings him in line with her own habitually secular and domestic points of view.”

Crusoe was also an unwitting solitary, who reluctantly gave in to his plight. As such, he appealed to Bishop, especially in his self-reliance. He made things from what’s at hand, just as she made poems from what surrounded her. She, too, had surrendered to her “exile” in Brazil.

There’s an ungentle madness to Crusoe the solitary, which also contrasts somewhat with Defoe’s Robinson. The latter reads the Bible and becomes increasingly more religious. Bishop’s Crusoe is more pagan, painting goats with berry juice, dreaming of “slitting a baby’s throat, mistaking it/ for a baby goat,” and has visions of endlessly repeating islands where he is fated to catalog their flora and fauna.

I’m tempted to see this last reference as almost a nightmare reflection of the poet’s own self-exile and imprisonment by her style: her oft-cited gift for description, which she saw as limiting.

Regardless of whether Bishop saw herself in her Crusoe, her own removal to New England from Brazil – to Harvard’s uninteresting lumber – must have caused equal disconnection, a “dislocating dizziness,” to borrow Goldensohn’s phrase.

“When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived,” Bishop wrote to Robert Lowell in 1948. In “Crusoe in England,” she captures the loneliness, displacement, and loss of an individual set adrift in emotional isolation, which leads to a kind of post-traumatic stress syndrome.

For Crusoe, his island life seemed interminable and insufferable, only to turn romantic and desirable when the experience ended.

It seems likely Bishop was thinking of her life in Brazil with Lota, which had become increasingly strained towards the end, until the latter’s suicide, and the poet’s life thereafter. That makes this poem, along with “One Art,” from the same collection, an elegy with a depth beyond its surface.

Here is a link to the complete text of “Crusoe in England,” which includes an audio recording of Bishop reading the poem: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/177903

–Scott Edward Anderson

Visions Coinciding: Celebrating Elizabeth Bishop’s Centenary

December 5, 2011

As readers of this blog know, 2011 marks the centenary of Elizabeth Bishop’s birth. I’ve been trying to celebrate it in as many ways as possible and get to some of the events throughout the year, as well as visiting her grave in Worcester, MA, and promoting her work on this blog and on Twitter by using #EB100.

Last week I attended Visions Coinciding: An Elizabeth Bishop Centennial Conference, organized by NYU’s Gallatin School and the Poetry Society of America.

The conference featured interdisciplinary responses to Bishop and her work, including a slide show and talk by Eric Karpeles exploring rarely seen images of Elizabeth Bishop and a screening of footage from Helena Blaker’s forthcoming documentary on Bishop’s years in Brazil.

The screening was followed by a discussion moderated by Alice Quinn, editor of Bishop’s posthumous collection Edgar Allen Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments, along with Blaker and Bishop scholars Brett Millier, Barbara Page, and Lloyd Schwartz.

Day two featured two lectures on Bishop’s relationship with Art. Peggy Samuels gave a fascinating exegesis of Bishop’s interest in and influence by the work of Kurt Schwitters and William Benton displayed slides of Bishop’s own paintings, sharing his insights on their context in modern art.

Jonathan Galassi moderated a lively discussion with the editors of recent collections of Bishop’s poetry, prose and correspondence, including Joelle Biele (Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker correspondence), Saskia Hamilton (Words In Air

, the Lowell-Bishop correspondence, and new edition of POEMS

), Lloyd Schwartz (new edition of PROSE

, as well as the Library of America edition of Bishop: Poems, Prose, Letters

), and Thomas Travisano (Lowell-Bishop correspondence).

All this was followed by a reading by NYU Gallatin students who each read a Bishop poem and one of their own by way of response and, finally, a star-studded lineup of contemporary American poets, including John Koethe, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Mark Strand reading poems by Bishop.

Poet Jean Valentine read Bishop’s translation of Octavio Paz’s “Objects & Apparitions” with the original read by Patrick Rosal. Maureen McLane read from her creative work-in-progress “My Elizabeth Bishop; My Gertrude Stein.”

This week is the opening of Elizabeth Bishop: Objects & Apparitions at the Tibor De Nagy Gallery in New York. The show comprises rarely exhibited original works by Bishop, including watercolors and gouaches, as well as two box assemblages inspired by the work of Joseph Cornell.

The exhibition also includes the landscape painting Miss Bishop inherited and that she wrote about in “Poem,” which begins

About the size of an old-style dollar bill,

American or Canadian,

mostly the same whites, gray greens, and steel grays

-this little painting (a sketch for a larger one?)

has never earned any money in its life.

Unfortunately, I’m going to miss the exhibit of her papers at the Vassar College Main Library, From the Archive: Discovering Elizabeth Bishop, which is on view until December 15th.

But there’s still time to celebrate Bishop’s centenary — until her 101st on February 8, 2012.

I love a poet with a sense of humor and who delights in wordplay, especially when she achieves her poem’s aims while making the reader smile.

Those who know me or read my poetry blog or follow me on Twitter or have been on my National Poetry Month email list for some time know that Elizabeth Bishop is my favorite poet. And you also know that this year marks the centennial of her birth (born 8 February 1911). I’ve been celebrating this important centennial in a variety of ways.

I’d like to close this year’s National Poetry Month with a poem by Ms. Bishop called “Filling Station.” I suggest you read it out loud and pay attention to the alliteration and internal rhymes.

It starts with an observation of a “dirty” family filling station, run by a father in a “dirty,/ oil-soaked monkey suit” with “several quick and saucy/ and greasy sons.” They are “all quite thoroughly dirty,” which creates an incantation of “oily” and “dirty,” evolving into almost a portmanteau of dirty and oily in “doily.”

Bishop is playful in this poem and when she concludes with the final stanza by repeating “oi” and “so” and “-y” sounds, culminating in that brilliant arrangement of oil cans, I can’t help chuckling no matter how many times I read it.

Somebody loves us all, indeed. Happy Birthday, Ms. Bishop.

Here is Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, “Filling Station”

Oh, but it is dirty!

—this little filling station,

oil-soaked, oil-permeated

to a disturbing, over-all

black translucency.

Be careful with that match!

Father wears a dirty,

oil-soaked monkey suit

that cuts him under the arms,

and several quick and saucy

and greasy sons assist him

(it’s a family filling station),

all quite thoroughly dirty.

Do they live in the station?

It has a cement porch

behind the pumps, and on it

a set of crushed and grease-

impregnated wickerwork;

on the wicker sofa

a dirty dog, quite comfy.

Some comic books provide

the only note of color—

of certain color. They lie

upon a big dim doily

draping a taboret

(part of the set), beside

a big hirsute begonia.

Why the extraneous plant?

Why the taboret?

Why, oh why, the doily?

(Embroidered in daisy stitch

with marguerites, I think,

and heavy with gray crochet.)

Somebody embroidered the doily.

Somebody waters the plant,

or oils it, maybe. Somebody

arranges the rows of cans

so that they softly say:

ESSO—SO—SO—SO

to high-strung automobiles.

Somebody loves us all.

–Elizabeth Bishop

Here’s a recording of Ms. Bishop reading this poem from Poetry Foundation/Bishop