Why a Writing Retreat in the Azores?

May 25, 2023

People ask me why a Writing Retreat in the Azores? My first answer to that question is: because I want to share my ancestral island and its natural and cultural gifts with you. My second answer is: what better place to practice deep attention to our writing than on a remote island in the middle of the Atlantic?

Writing without distraction is particularly difficult these days, that’s why I’ve designed the Azores Writing Retreat around what I’m calling Deep Attention. Everything we do will be guided by this framework, designed to develop a practice we can take with us long after the retreat is over.

Deep Attention is a practice I’m developing in response to our age of distraction. Paying attention in an age of distraction is hard. At any given moment, there is a myriad of distractions tempting us away from our writing.

If we’re paying attention, however, we can put our busy lives in perspective, create a context for what we’re doing on this planet. Living like this, life is not about going through the motions; rather, we actively participate in life, in all its facets.

Deep Attention sets us up for opening the writing brain, for preparing that muscle to do its best work. Working the writing-brain in this way makes it easier to pay attention, not only to our surroundings, but to our words and what the piece of writing is trying to say. It’s also a reciprocal, regenerative act: paying deep attention informs our writing and our writing helps us pay deeper attention.

For me, the practice of Deep Attention is part of the act of writing, as the practice of writing is part of the act of paying attention, a cyclical, symbiotic relationship. This type of attentiveness is akin to what Zen practitioners call deep listening.

As Zen practice implies, deep listening requires complete receptivity—an openness and attentiveness to what’s possible and to asking questions. If we have a question to answer through our writing, we need to ask it. Nevertheless, it sometimes seems like our minds are on autopilot and we are not truly paying attention, causing us to miss both questions and answers.

This deep listening and attentiveness are a form of tuning to the right frequency. Like the dial on an old car radio, if you turn a little too much to the right or left, you lose the signal. Through the act of paying attention, we fine-tune our ability to land on the right frequency.

Deep Attention requires a two-fold approach to paying attention: outward and inward. Outward: what’s going on around you and what you see, what you notice. Inward: what’s going on within you and your reactions to what you notice. Combined, this inward and outward focus develops our ability to see things others do not see and allows us to call attention to those things in our writing. Inward-focused attention also helps us turn observation into a piece of writing, aligning the frequencies and images to unlock the stories within us.

Deep Attention is, in part, a form of showing up, of being fully present, fully engaged. Distractions govern so much of our lives—from social media to work life—we so rarely allow time for deep attentiveness. If we make it a practice, however, we can begin to form insights and become more receptive to the poetry of our everyday lives and bring it into our writing.

Join me on the island of São Miguel for this five-day Deep Attention Retreat, October 13-18, 2023, where we’ll learn the practice Deep Attention, immerse ourselves in the incredible nature of the “Hawaii of Europe,” savor the delectable cuisine of the Azores, and get a lot of writing done.

Reserve your spot today: Azores Writing Retreat.

If you’ve ever dreamed of exploring the art of writing on an enchanted island, this is your opportunity! Join me for this unique writing retreat in the Azores, Portugal — the “Hawaii of Europe.”

We’ll spend five days on magical São Miguel, one of the nine islands of the Azorean archipelago, “an otherworldly paradise for nature lovers and outdoor adventurers,” as described by Travel & Leisure. We’ll Immerse ourselves in the luxury of one of the island’s most elegant hotels, situated on an 18th century orchard estate, famous among islanders for blending tradition and nature. We’ll savor the cuisine of the island, which fuses farm-to-table and ocean-caught freshness with gourmet takes on traditional Portuguese recipes. And we’ll explore some of the natural wonders of the island, including the hot springs of Furnas, the beauty of the twin volcano lakes at Sete Cidades, and forest bathing in Pinhal da Paz (the pine grove of peace).

During this retreat, you’ll have ample time to write. After a delicious Azorean breakfast, I’ll lead a guided, intention-setting session before you set out to write on your own in the seclusion of the gardens or wherever you choose on the hotel grounds.

I’ll share my mindful approach to writing, what I call “Deep Attention,” a creative practice of looking at the world with intention and without distraction, which I first outlined in this essay. The retreat will incorporate this deep attention practice to help you tap into your creativity, gain new perspectives, and get beyond your daily, habitual obsessions and distractions.

Lunch will be served at the hotel or on guided field trips. After the afternoon field trip, you’ll have an opportunity for another writing session or free time to relax, use the spa, pool, or soak in the heated plunge pool in the pineapple greenhouse. After dinner, you’ll have an opportunity to share your work or reflect upon your experiences.

I’ve designed this retreat to show you some of the best my ancestral island has to offer, and I’ve hand-picked the hotel, restaurants, excursions, and experiences to ensure you will be inspired to write in a relaxed, mindful, and encouraging environment.

Early Bird Discount ends on June 15th, so sign up today!

Find out more: https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

Last summer, I started a project to translate the Azorean poet Pedro da Silveira’s first book A ilha e o mundo (The Island and the World), which came out in 1952.

I had reviewed the late George Monteiro’s translation of Silveira’s last book, published in a bilingual edition by Tagus Press in the States and simultaneously by Letras Lavadas in the Azores in 2019 as Poems in Absentia & Poems from The Island and the World. In fact, the second half of that title was a misnomer; the book included only a few poems from Silveira’s first book–poems that had previously appeared in a Gávea-Brown anthology from the 1980s and sort of slapped on to the end of the book. (Silveira was born on Flores Island in 1922 and died in Lisbon in 2003.)

What struck me immediately about Silveira’s poetry—in Monteiro’s translation first and then in reading the facing Portuguese—was the depth of its feeling, the simplicity and directness of its language, and the brilliant tapestry woven by strands of memory, naming, and observations of nature. Indeed, all aspects that are found in my own poetry; hence, I felt a certain kinship with Silveira’s work straight away.

And yet, I was equally struck by the dearth of his poetry available in translation. How could such a seemingly important poet be so little represented in English translation? How much richer would the world of poetry–and the world of poetry-in-translation–be with Silveira’s body of work. And how much richer would be our lives in the Azorean diaspora with his sentiments, steadfast observations, and steady poetic hand.

I started with the second poem in the book, “Ilha”; this was likely the first poem I ever read by Silveira in translation, from that old Gávea-Brown anthology previously mentioned.

Here is the entire poem in its original Portuguese:

ILHA Só isto: O céu fechado, uma ganhoa pairando. Mar. E um barco na distância: olhos de fome a adivinhar-lhe, à proa, Califórnias perdidas de abundância.

As I tend to do in my method of translation, I first read the poem straight through and then wrote an impression or literal reading as I understood it:

Just this:

The closed sky, a heron

Hovering. Sea. A boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes guessing, at the prow,

Californias lost of abundance.

A bit clunky and prosaic, and probably unworthy. I prefer to not read another’s translation (if there is one) while translating a poem lest I be influenced by it, so Monteiro’s sat on the shelf.

One thing troubled me, however. The bird. Where did that heron come from? Surely, I remembered it from Monteiro’s version. “Ganhoa,” at first, I thought was a misprint of “ganhou” – who won? – but that made absolutely no sense, so I went with heron. But what was a heron doing in this scene? Were herons even found in the Azores?

Reluctantly, I checked Monteiro’s translation. Sure enough, there it was, “heron.” It struck a dissonant chord with me now. A heron. Really? Again, I wondered whether herons were found in the Azores and turned to the Internet.

Yes, there were at least ten species of heron that have been noted on these islands, including great blues and little egrets, which according to the website whalewatchingazores.com have been sighted, but “not regularly”; the species is classified as an “uncommon vagrant” on the islands. And, most recently, a confirmed sighting of another species, the yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) was described in a scientific paper by João Pedro Barreiros. Most likely, however, this one was blown east by a strong, errant wind from the west. Several herons were known to stop-over on their migratory path from Africa to northern climes and back.

Still, heron didn’t seem correct, to me, given the scene described. The use of Mar all alone. And the boat seemed to imply open waters rather than shoreline.

Herons are marsh-dwelling, shoreline species for the most part, so I was perplexed why they might be hovering “at Sea” or the “open ocean,” as I envisioned it. Were they blown off-course and out of their range? That would surely change the nature of this poem, which I assumed was about emigration or the emigrant returned or the desire to emigrate but also remain tied to the island. If it was not a heron, what was it then? What else might “hover” over the open ocean?

I typed “ganhoa” into Google. The almighty, all-seeing Google asked if I meant “ganhos” earnings; no, I did not. This was not a poem set in the halls of finance or a casino in Monaco. So, I clicked on “search instead for ganhoa” and up came a page from Priberam dicionário. I had my bird! The yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis atlantis)…surely this bird would hover over the prow or bow of the boat, and even the stern, looking for a handout. A ganhoa recupera os seus ganhos. (The gull recovers its winnings.)

Here is my version of Pedro da Silveira’s “Island”:

Just this:

The closed sky, a yellow-legged gull

hovering. Open ocean. And a boat in the distance:

Hungry eyes, at the bow, divining,

lost Californias of plenty.

(Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

____

(This text was adapted from a paper delivered at the Colóquio celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pedro da Silveira, “Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedro cultural,” at the University of the Azores in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, in September 2022.)

Speaking of the Azores: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

My Year in Writing: 2022

November 28, 2022

Now is the time, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing. It’s been a pretty productive year, considering it also included a move from Brooklyn to the Berkshires:

Published Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations (Shanti Arts)

Book launch for Wine-Dark Sea online with Kathryn Miles (Feb)

Appearance on Portuguese American Radio Hour with Diniz Borges (March)

World Poetry Day/Cagarro Colloquium reading (March)

Book launch with Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (March)

Book signing at Terrain.org booth at #AWP22 in Philadelphia (March)

Wine-Dark Sea gets “Taylored” by @taylorswift_as_books on Instagram! (March)

Lecture at University of the Azores: Mesa-redonda Poesia, Tradução e Memória (April)

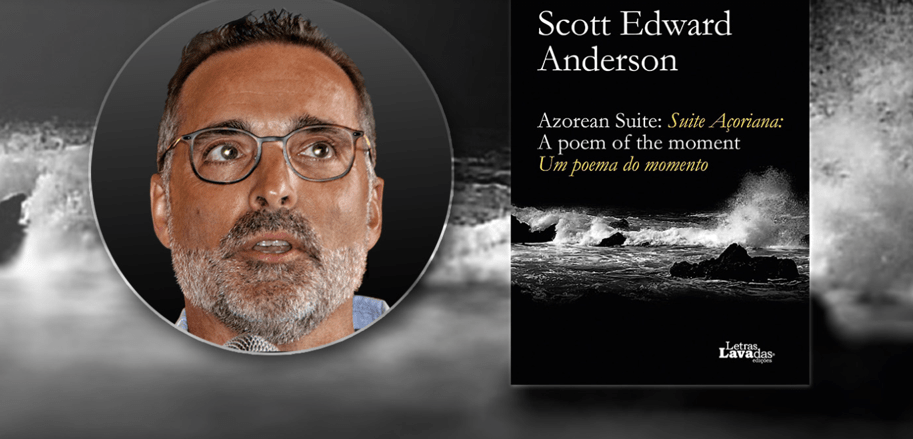

Azores launch for Wine-dark Sea and Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana at Letras Levadas in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, Azores, with Leonor Sampaio Silva (April)

Açores Hoje television interview with Juliana Lopes on RTP Açores (April)

Terrain.org Reading Series with Joe Wilkins and Betsy Aoki (April)

“Phase Change” and “Under the Linden’s Spell” reprinted in TS Poetry’s Every Day Poems (online/email)

“Midnight Sun” and “Shapeshifting” reprinted in Earth Song: a nature poems experience (anthology), edited by Sara Barkat and published by TS Poetry Press

Named Ryan Observatory’s first Poet Laureate

Mentored 2 students in Creative Nonfiction for Adroit Journal Summer Mentorship Program (June/July) [UPDATE: one of the students I mentored got accepted into the University of Pennsylvania, early decision! So proud of her!]

Translated Pedro da Silveira’s A ilha e o mundo, his first book of poems (1952)

Excerpts from Corsair of the Islands, my translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s Corsário das Ilhas, published in Barzakh Magazine (online) (August)

Panelist/presenter at Colóquio: Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedo cultural, University of the Açores: On Translating Pedro da Silveira’s A Ilha (September)

Lançamento da obra Habitar: um ecopoema, Margarida Vale de Gato’s translation of Dwelling: an ecopoem, published by Poética Edições, with Nuno Júdice, Luís Filipe Sarmento, and Margarida Vale de Gato, at FLAD in Lisbon (September)

Guest lecturer in Creative Writing at University of the Azores (Leonor Sampaio Silva, professora)

Panelist/presenter at 36th Colóquio da Lusofonia, Centro Natália Correia, Fajã de Biaxo, São Miguel, Azores: reading from Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana with Eduardo Bettencourt Pinto (October)

#YeahYouWrite Catskill Reading at Fahrenheit 451 House, Catskill, NY w/Stephanie Barber, Laurie Stone, and Sara Lippmann (October)

Guest Writer at UConn Stamford creative writing class (Mary Newell, professor) (October)

Poet & Astronomer in Conversation (with Derrick Pitts, Chief Astronomer of the Franklin Institute) at Ryan Observatory at Muddy Run, PA (November)

“Wine-Dark Sea” (poem) published in American Studies Over_Seas (November)

20th Anniversary of residency at Millay Arts and writing of Dwelling: an ecopoem (November) [UPDATE: Got asked to join the Board of Millay Arts in December.]

Selections from Habitar: um ecopoema published in Gávea-Brown (US) and Grotta (Azores)

Book reviews in Gávea-Brown and Pessoa Plural [Postponed until 2023.](December)

My essay, “Açorianidade and the Radiance of Sensibility,” accepted by Barzakh Magazine for publication in Winter 2023 issue. (December)

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.”

Like I said last year, I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

Tonight, I’m reading from my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations in Terrain.org’s reading series. You can join us by registering here for the event. Hope to see you there!

I’ll be reading with two other poets, Joe Wilkins and Betsy Aoki. Betsy is an associate poetry editor with Terrain, which has published several of my poems over the years. Her colleague, Derek Sheffield, will be our host. Derek is a fine poet in his own right, and he has a new book out called Not For Luck, which poet Mark Doty selected for the Wheelbarrow Books Poetry Prize, and it was published by Michigan State University Press.

Derek has been called “a post-romantic nature poet,” in a recent review and, as the reviewer went on to say, his “poems are colored by a sense of separateness from nature and a recognition that language itself impedes any immediate communion with the world.” (Those of you familiar with my book Dwelling: an ecopoem, will understand why I find Derek’s work interesting and simpatico.)

I should also mention that he wrote a great blurb for my new book, for which I am truly grateful. And he has some of the longest poem titles I’ve ever seen (the one below is not even close to the longest), which is always fun.

Here is Derek Sheffield’s

“At the Log Decomposition Site in the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, a Visitation”

Below thick moss and fungi and the green leaves

and white flowers of wood sorrel, where folds

of phloem hold termites and ants busily gnawing

through rings of ancient light and rain, this rot

is more alive, says the science, than the tree that

for four centuries it was. Beneath beetle galleries

vermiculately leading like lines on a map

to who knows where, all kinds of mites, bacteria,

Protozoa, and nematodes whip, wriggle, and crawl

even as my old pal’s bark of a laugh comes back:

“He’s so morose you get depressed just hearing

his name,” he said once about a poet we both liked.

Perhaps it’s the rust-red hue of his cheeks

in the spill of woody bits. Or something in the long shags

of moss draping every down-curved limb. He’d love to be

right now a green-furred Sasquatch tiptoeing

among the boles of these firs alive since the first

Hamlet’s first soliloquy. He’d be in touch,

he said in an email, as soon as the doctors cleared him.

When this tree toppled, the science continues, its death

went through the soil’s mycorrhizae linking the living

and the dead by threads as fine as the hairs appearing

those last years along Peter’s ears, and those rootlets

kept rooting after. That email buried in my Inbox.

Two lines and his name in lit pixels on my screen.

What if I click Reply? That’s what he would do,

even out of place and time, here in the understory’s

lowering light where gnats rescribble their whirl

after each breath I send.

–Derek Sheffield, from Not For Luck, originally appeared in Otherwise Collective’s Plant-Human Quarterly

Photo by Ana Cristina Gil, University of the Azores.

My apologies for not being on top of my game with regards to National Poetry Month Mailings this year. Samantha and I just returned from an emotional trip to our beloved island of São Miguel, in the Azores, after two years away.

It was emotion-filled not only because the pandemic kept us way for two years—we had tried to go back as recently as December, but Omicron dissuaded us—but because in the interim years we had determined that we want to divide our time between there and our new home in the Berkshires and this trip solidified and confirmed that plan.

On top of that, we held a ceremony to place a plaque at the Praça do Emigrante (Emigrant Square) honoring the memory and sacrifice of my two great-grandparents who emigrated from the island in 1906. Joining us were cousins from my family there, the Casquilho family, along with the director and staff from the Associação dos Emigrantes Açorianos.

It was a windy afternoon, and the waves were crashing against the rocky shore along the north coast of the island, as if the spirit of my great-grandparents were making their presence known.

All this to say that I’m behind in my weekly mailings and I apologize. This week, I’m going to share post one of my translations of the great Azorean poet Vitorino Nemésio, “Ship,” which I hope you will enjoy. It originally appeared in Gávea-Brown Journal and was reprinted in my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. Here it is in the original Portuguese and in my translation:

Navio

Tenho a carne dorida

Do pousar de umas aves

Que não sei de onde são:

Só sei que gostam de vida

Picada em meu coração.

Quando vêm, vêm suaves;

Partindo, tão gordas vão!

Como eu gosto de estar

Aqui na minha janela

A dar miolos às aves!

Ponho-me a olhar para o mar:

—Olha-me um navio sem rumo!

E, de vê-lo, dá-lho a vela,

Ou sejam meus cílios tristes:

A ave e a nave, em resumo,

Aqui, na minha janela.

—Vitorino Nemésio, Nem Toda A Noite A Vida

___

Ship

My flesh is sore

from the landing of some birds

I don’t know where they’re from.

I only know that they, like life,

sting in my heart.

When they come, they come softly;

leaving, they go so heavy!

How I like to be

here at my window

giving my mind over to the birds!

I’m looking at the sea:

look at that aimless ship!

And, seeing it, give it a lamp[i],

or my sad eyelashes:

the bird and the ship, in a nutshell,

here, at my window.

—translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

[i] For “vela,” I like “lamp” here, rather than “candle” or “sail,” because it echoes the idea of lighting a lamp to draw in a weary traveler—although I think “salute” or “sign” might also work, although not technically accurate. Also “lamp” hearkens back to Nemésio’s stated desire, expressed in his Corsário das Ilhas, which I’ve been translating for Tagus Press, of wanting to be a lighthouse keeper.

WINE-DARK SEA BOOK LAUNCH & READING

March 2, 2022

In conversation with Kathryn Miles

On #pubday eve, Kathryn Miles and I got together to chat about my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. We had a wide-ranging conversation about the book, specific poems, finding love at middle age, the idea of home, and the Azores — and I even read a poem in Portuguese.

Have a look here:

The book came out March 1st and is available through the links on my website: scottedwardanderson.com/wine-dark-sea

My Year in Writing: 2021

November 24, 2021

Now is the time of year, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing.

What a year it’s been, deepening my connections to my ancestral homeland of the Azores, as well as my ties to the diaspora throughout North America. Here we go:

- Signed contract with Shanti Arts for Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations to be published in Spring 2022. (Technically signed this at the very end of 2020, but thought it was worth mentioning again.)

- Published “Five Poems by Vitorino Nemésio” in my English translations in Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies.

- Interview and review by Esmeralda Cabral appeared in Gávea-Brown and was later translated into Portuguese by Esmeralda and Marta Cowling and appeared in Diário dos Açores.

- Published four translations by Margarida Vale de Gato from Dwelling in Colóquio/Letras by the Gulbenkian Foundation. And signed contract with Poética Edições for Habitar: uma ecopoema, translation by Margarida of my book Dwelling: an ecopoem. Received funding for Margarida’s translation from FLAD.

- Associação dos Emigrantes Açorianos AEA video presentation, “Açores de Mil Ilhas” for World Poetry Day.

- Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana review by Maria João Covas (video); and translation of Vamberto Freitas’s (2020) review published in Portuguese-American Journal.

- Wrote a poem in português for Letras Lavadas’s celebration, Dia Internacional da Mulher. Here is the video presentation, which includes the fabulous Aníbal Pires reading my poem, “A outra metade do céu/The other half of the sky.”

- Talk for New Bedford Whaling Museum on “Azorean Suite: A Voyage of Discovery Through Ancestry, Whaling, and Other Atlantic Crossings”

- Dwelling featured in a class at Providence College on Environmental Philosophy, thanks to Professor Ryan Shea; spent a week there, including teaching three classes and giving a reading/talk at the PC Humanities Forum.

- Readings: RONDA: Leiria Poetry Festival (March); Filaments of Atlantic Heritage (March), Cravos Vermelhos Oara Todos os Povos/World Poetry Movement Reading (April); A Nova Revolução dos Cravos (April), Cagarro Colloquium—Azores Day & launch (May); ASLE Spotlight Series (June); Juniper Moon’s Sunday Live reading series (August), LAEF Conference/PBBI (October); and A Voz dos Avós Conference/PBBI (November). Phew, I’m exhausted just writing that schedule!

- Translated poems by Luís Filipe Sarmento, Ângela de Almeida, and Adelaide Freitas.

- Panelist for PALCUS on Embracing Modern Portuguese Culture (spoke about Cagarro Colloquium, translation, etc.).

- Participated in “Insularity and Beyond: The Azores & American Ties” webinar with University of the Açores.

- Participated in session with Margarida Vale de Gota’s translation students at University of the Lisbon via Zoom.

- Recorded a video—em português—for Letras Lavadas’s second anniversary of bookstore in PDL

- Finished a draft of my translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s Corsário das Ilhas and revisions corresponding to new (2021) Portuguese edition.

- Published my talk from PC Humanities Forum in Gavéa-Brown.

- Published “Wine-Dark Sea” (poem) in America Studies Over_Seas.

- Published two poems, “The Pre-dawn Song of the Pearly-eyed Thrasher” and “Under the Linden’s Spell,” in The Wayfarer.

- Published “Phase Change” (poem) in ONE ART (online poetry journal).

- Scrapped portions of my work-in-progress, The Others in Me, after consulting with two writer friends about it, but found a new approach through working with Marion Roach Smith, which I will start in 2022…

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.” I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

Please join me this Thursday, 3 June, at 7PM EDT, for a reading and talk I’m giving for the New Bedford Whaling Museum, which focuses on the connections between the Azores, New Bedford, and Rhode Island, whaling, and other Atlantic Crossings.

Inspired by my explorations into my family heritage, which in turn inspired my book-length poem Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana, this reading and talk will explore the journeys of various waves of immigrants to America and their connection across the Atlantic to the Azores.

I’ll share passages from Azorean Suite, as well as from my work-in-progress, a research-driven memoir called “The Others in Me: A Journey to Discover Ancestry, Identity, and Lost Heritage.”

The ZOOM event is past, but you can watch the video here: Whaling Museum

Hope to “see” you there!

National Poetry Month 2021, Bonus Week: My translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s “A Árvore do Silêncio”

May 2, 2021

For my bonus post this year, wrapping up this Poetry Month featuring poets of the Azores and its Diaspora, I want to share one of my translations of the great 20th Century Azorean poet Vitorino Nemésio. (This translation appears in the current issue of Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, along with four others.)

Photo by Manuel de Sousa, Creative Commons License

A poet, essayist, and public intellectual, Nemésio was born on Terceira Island in 1901 and is best known for his novel Mau tempo no canal (1945), which was translated into English by Francisco Cota Fagundes and published as Stormy Isles: An Azorean Tale.

In 1932, the quincentennial year of Gonçalo Velho Cabral’s “discovery” of the Azores, Nemésio coined the term “açorianidade,” which he would explore in two important essays, and which would become the subject of much debate over the years. There are those who see the term as somewhat limiting: describing as it does a specific, fixed set of qualities of the island condition—insularity, for example—that belies a greater dynamism in the spirit of the islanders.

Nevertheless, I think its usefulness as a term is somewhat expanded when we look at what Nemésio himself said about it, reflecting the entirety of his term rather than one dimension of it. Instead of limiting it as a descriptor to what it’s like to be born on the islands, Nemésio asserted that it was appropriate, too, for those who emigrated from the islands, as well as those who later returned. (And, by extension, as I said in a recent interview, I like to think he intended it to continue through or beyond the generations.)

The term, wrote Antonio Machado Pires in his essay, “The Azorean Man and Azoreanity,” “not only expresses the quality and soul of being Azorean, inside or outside (mainly outside?) of the Azores, but the set of constraints of archipelagic living: its geography (which ‘is worth as much as history’), its volcanism, its economic limitations, but also its own capacity as a traditional ‘economy’ of subsistence, its manifestations of culture and popular religiosity, their idiosyncrasy, their speaking, everything that contributes to verify identity.”

As a “warm-up exercise” for translating Nemésio’s travel diary, Corsário das Ilhas (1956), for which I am currently under contract with Tagus Press of UMass Dartmouth (with financial support from Brown University), I started with some of his poems. And I hope to continue with more, because Nemésio is worthy of a larger audience here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief tour of some of the poetry of the Azores and its Diaspora.

Here is Vitorino Nemésio’s “A Árvore do Silêncio” and my translation, “The Tree of Silence”:

A ÁRVORE DO SILÊNCIO

Se a nossa voz crescesse, onde era a árvore?

Em que pontas, a corola do silêncio?

Coração já cansado, és a raiz:

Uma ave te passe a outro país.

Coisas de terra são palavra.

Semeia o que calou.

Não faz sentido quem lavra

Se o não colhe do que amou.

Assim, sílaba e folha, porque não

Num só ramo levá-las

com a graça e o redondo de uma mão?

(Tu não te calas? Tu não te calas?!)

—Vitorino Nemésio de Canto de Véspera (1966)

_____________

THE TREE OF SILENCE

If our voice grew, where was the tree?

To what ends, the corolla of silence?

Heart already tired, you are the root:

a bird passes you en route to another country.

Earthly things are word.

Sow what is silent.

It doesn’t matter who plows,

if you don’t reap what you loved.

So, why not take them,

syllable and leaf, in a single bunch

with the graceful roundness of one hand?

(Don’t you keep quiet? Don’t you keep quiet?!)

—translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

from Gávea-Brown—A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, vol. 43. Brown University, 2021