A few weeks from now—on May 8th, to be exact—poet Gary Snyder will complete his 95th trip around the Sun. That we have had Snyder on our planet for nearly a century—and may yet celebrate his hundredth with him—is a remarkable gift. Those of us lucky enough to have studied with him, in whatever capacity, have been doubly blessed, both by his instruction and by his example.

I’ve been thinking about Snyder a lot lately, partly because I’ve reached the same age he was when I studied with him and because what he taught me continues to resonate. (I’ve written about that experience elsewhere, here and here.)

But Snyder’s upcoming birthday isn’t the only reason he’s been on my mind. It’s because we need his example now more than ever. We need his fierce compassion. We need his brand of resistance, rooted in a holistic, ecological worldview that calls for a fundamental shift in how we live, think, and act.

Snyder challenges us to confront environmental degradation and social injustice as intertwined crises, urging resistance to industrial capitalism, the culture of consumption, and the exploitation of both nature and people. This resistance, in his view, is not just political or economic, it’s also spiritual and intellectual. A path toward a more just, more sustainable way of being.

There are countless expressions of this ethic in his poetry—“For All,” from his Pulitzer Prize-winning Turtle Island (1974)), comes to mind. But today, I’m thinking about his “Smokey the Bear Sutra.” Snyder wrote it in 1969 for the Sierra Club Wilderness Conference and released it to the public domain so it could be freely shared.

In the poem, he reimagines Smokey the Bear, the iconic U.S. Forest Service symbol, not as a mascot, but as a reincarnation of the Vairocana Buddha, here to save not only the forests, but all living beings.

“My Smokey is essentially a dharmapala, a dharma protector, and I modeled him after the Japanese figure of Fudo,” Snyder later said. “In Sanskrit he has the name Achala, which means ‘immovable, unshakable,’ which is also what fudo means. He’s got a fierce visage and is usually pictured surrounded by flames, further evidence that the Forest Service’s Smokey is his North American incarnation.”

Snyder confided, “the sutra’s basic message is that our sacred responsibility is to protect all of life…to protect life down to the smallest little creature, protect our community, maintain our own practice, and honor impermanence, all at the same time.”

We need a little more of that sense of responsibility these days, especially considering the chaos swirling around us.

Here is Gary Snyder’s “Smokey the Bear Sutra”:

Once in the Jurassic about 150 million years ago, the Great Sun Buddha in this corner of the Infinite Void gave a discourse to all the assembled elements and energies: to the standing beings, the walking beings, the flying beings, and the sitting beings—even the grasses, to the number of 13 billion, each one born from a seed, assembled there: a Discourse concerning Enlightenment on the planet Earth.

“In some future time, there will be a continent called America. It will have great centers of power called such as Pyramid Lake, Walden Pond, Mt. Rainier, Big Sur, Everglades and so forth; and powerful nerves and channels such as Columbia River, Mississippi River, and Grand Canyon. The human race in that era will get into troubles all over its head and practically wreck everything in spite of its own strong intelligent Buddha-nature.”

“The twisting strata of the great mountains and the pulsings of volcanoes are my love burning deep in the Earth. My obstinate compassion is schist and basalt and granite, to be mountains, to bring down the rain. In that future American Era I shall enter a new form, to cure the world of loveless knowledge that seeks with blind hunger and mindless rage, eating food that will not fill it.”

And he showed himself in his true form of

SMOKEY THE BEAR

A handsome smokey-colored brown bear standing on his hind legs, showing that he is aroused and watchful.

Bearing in his right paw the Shovel that digs to the truth beneath appearances, cuts the roots of useless attachments, and flings damp sand on the fires of greed and war;

His left paw in the mudra of Comradely Display—indicating that all creatures have the full right to live to their limits and that deer, rabbits, chipmunks, snakes, dandelions, and lizards all grow in the realm of the Dharma;

Wearing the blue work overalls symbolic of slaves and laborers, the countless men oppressed by a civilization that claims to save but often destroys;

Wearing the broad-brimmed hat of the west, symbolic of the forces that guard the wilderness, which is the Natural State of the Dharma and the true path of man on Earth:

all true paths lead through mountains—

With a halo of smoke and flame behind, the forest fires of the kali-yuga, fires caused by the stupidity of those who think things can be gained and lost whereas in truth all is contained vast and free in the Blue Sky and Green Earth of One Mind;

Round-bellied to show his kind nature and that the great Earth has food enough for everyone who loves her and trusts her;

Trampling underfoot wasteful freeways and needless suburbs, smashing the worms of capitalism and totalitarianism;

Indicating the task: his followers, becoming free of cars, houses, canned foods, universities, and shoes, master the Three Mysteries of their own Body, Speech and Mind, and fearlessly chop down the rotten trees and prune out the sick limbs of this country America and then burn the leftover trash.

Wrathful but Calm. Austere but Comic. Smokey the Bear will Illuminate those who would help him; but for those who would hinder or slander him . . .

HE WILL PUT THEM OUT.

Thus his great Mantra:

Namah samanta vajranam chanda maharoshana Sphataya hum traka ham mam

“I DEDICATE MYSELF TO THE UNIVERSAL DIAMOND

BE THIS RAGING FURY DESTROYED.”

And he will protect those who love the woods and rivers, Gods and animals, hobos and madmen, prisoners and sick people, musicians, playful women, and hopeful children;

And if anyone is threatened by advertising, air pollution, television, or the police, they should chant SMOKEY THE BEAR’S WAR SPELL:

DROWN THEIR BUTTS

CRUSH THEIR BUTTS

DROWN THEIR BUTTS

CRUSH THEIR BUTTS

And SMOKEY THE BEAR will surely appear to put the enemy out with his vajra-shovel.

Now those who recite this Sutra and then try to put it in practice will accumulate merit as countless as the sands of Arizona and Nevada.

Will help save the planet Earth from total oil slick.

Will enter the age of harmony of man and nature.

Will win the tender love and caresses of men, women, and beasts.

Will always have ripened blackberries to eat and a sunny spot under a pine tree to sit at.

AND IN THE END WILL WIN HIGHEST PERFECT ENLIGHTENMENT

. . . thus we have heard . . .

–Gary Snyder

(A note at the end of the poem states that it “may be reproduced free forever.”)

In December 1994, I attended a poetry reading at Poets House in New York by two Portuguese poets, Nuno Júdice and Pedro Tamen, along with the translator, Richard Zenith. Little did I know that this event would have an impact on the profound journey into my ancestral roots in Portugal and the Azores.

After my Portuguese grandfather passed away in September 1993, I was at a loss to uncover our family’s history, which he had been reluctant to share. Hearing Júdice and Tamen read their poems in Portuguese the following December was a revelation of sorts—here were real, live Portuguese poets speaking the language of my ancestors.

The dearth of first-hand accounts and available source materials kept me from learning my family’s Portuguese Azorean history for many years and, frankly, life got in the way of digging deeper. When my father died in 2016, I realized that all my family’s histories were available to me, except one part—the Portuguese. By then, Ancestry.com had made many research materials available online for the first time, and a group of Azorean Genealogists gathered on a listserv to share information, leads, and help translate documents from the Azores, much of which had also become available online in the form of scanned records from the parish archives from the Azores. Suddenly, my research got easier.

In 2018, I made my first trip to the Azores and Portugal, and before going, I reached out to Nuno Júdice, whose contact information I had kept from that poetry reading decades ago.

To my surprise, Nuno remembered me, and we arranged to meet during my visit to Lisbon in July of that year. We spent a delightful evening together, with Nuno sharing insights into Portuguese poetry, history, and culture. Our connection deepened further when he invited me to write a foreword for David Swartz’s English translation of his novella, The Religious Mantle, and later, he published several of my poems in a literary journal he edited.

In 2020, Nuno graciously provided a blurb for my book Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana, celebrating the work as a poetic exploration of ancestral memory and the experiences of Portuguese emigrants.

Our paths continued to intertwine as the translator Margarida Vale de Gato, whom Nuno had earlier recommended for my poems, agreed to translate my book Dwelling: an ecopoem into Portuguese. Nuno even agreed to help launch the translated edition, Habitar: um ecopoema, in Lisbon in September 2022. In many ways, this felt like coming full circle from our initial encounter at that poetry reading nearly three decades ago.

In a serendipitous twist, Júdice revealed that he had met one of my teachers, the renowned poet Gary Snyder, whom Margarida had also translated, in Madrid in the 1980s. He even shared a draft of a poem he had written about that encounter, further solidifying the interconnectedness of our poetic journeys. When Nuno Júdice passed away last month unexpectedly, I was deeply sad to hear the news from David Swartz; I had just been thinking about Nuno and had planned to write to him. He would have turned 75 years old later this month.

Here is Nuno Júdice’s poem, “Madrid, Anos 80” and my translation from the Portuguese:

MADRID, ANOS 80

Cruzei-me uma vez com Gary Snyder nas Bellas Artes

de Madrid. Eu vinha com livros espanhóis – poesia, e algum

Borges, onde há sempre coisas novas – e cruzei-me com Gary

Snyder, que vinha de ler poemas, mas quando o soube já

a leitura tinha acabado. Também não sei se o iria ouvir: não é

todos os dias que se está em Madrid, com tempo para ir

às livrarias e espreitar museus; e ouvir Gary Snyder pode

não dar jeito ou, pelo menos, obrigar a que se perca alguma coisa

que tão cedo não se voltará a ver. Foi assim que, antes de ir à livraria,

eu tinha passado pelo Caspar David Friedrich, no Prado,

perseguindo montanhas e ruínas da velha Alemanha. Ao sair dali,

com os olhos enevoados pelo mar do Norte, como iria

entrar numa sala para ouvir Gary Snyder? Da próxima vez

que estiver em Madrid, porém, não vai ser assim: e se me cruzar,

nas Bellas Artes, com um poeta que acabe de ler poemas,

mesmo que eu venha da livraria, e tenha passado pelo Prado,

vou arranjar tempo para o ouvir – em homenagem a

Gary Snyder, que não tive tempo

para ouvir.

Nuno Júdice, 26-11-2000

__

MADRID, 80’s

I crossed paths with Gary Snyder once, at Bellas Artes

in Madrid. I was carrying Spanish books – poetry, and some

Borges, where there are always new things – and I bumped into Gary

Snyder, who came to read poems, but by the time I found out

the reading was over. I didn’t know if I would listen to him either: it isn’t

every day that you’re in Madrid, with time to go

to bookstores and look around museums; and listening to Gary Snyder might

not be useful or, at least, make you miss something

that you won’t see again anytime soon. So, before going to the bookstore,

I had passed by Caspar David Friedrich, in the Prado,

chasing mountains and ruins of old Germany. As I left,

with eyes clouded by the North Sea, how was I going to

walk into a room to listen to Gary Snyder? The next time

when I’m in Madrid, however, it won’t be like that: and if you bump into me,

in Bellas Artes, with a poet who has just finished reading poems,

even if I’m coming from the bookstore, and have just passed through the Prado,

I will make time to listen – in honor of

Gary Snyder, who I didn’t have time

to hear.

Translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

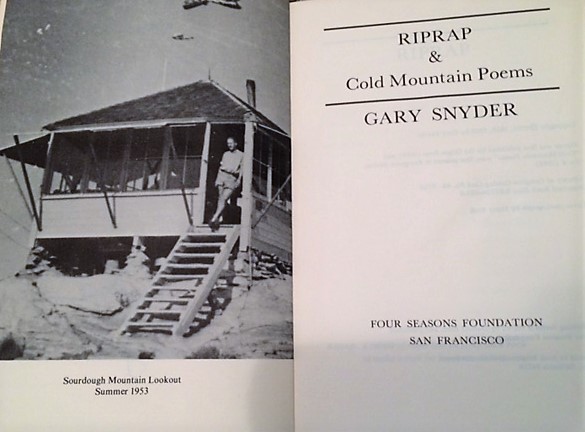

The author’s copy of Riprap & Cold Mountain Poems by Gary Snyder.

Schuykill Valley Journal Online published my essay on Gary Snyder’s “Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout” last month. Here are the introductory paragraphs and a link to the full essay:

To get to Sourdough Mountain Lookout, you hike a good five miles, gaining 5000 feet or more of elevation. The terrain is rugged and the hiking strenuous, but that’s to be expected in the Northern Cascades. Located 130 miles northeast of Seattle, Washington, the Forest Service opened one of its first lookouts here in 1915.

The view from the lookout station, constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, is a postcard in every direction: Hozomeen Mountain and Desolation Peak looking north, Jack and Crater mountains out east, Pyramid and Colonial peaks to the south with Ross and Diablo lakes directly below, and, as if not to be outdone, the Picket Range is off to the west. This is impressive country and you can understand why it’s been an inspiration to poets and writers for generations.

Poet Gary Snyder was 23 when he worked as a fire-spotter on Sourdough Mountain in 1953.

Today is poet Gary Snyder’s birthday. He is 83 years old.

Today is poet Gary Snyder’s birthday. He is 83 years old.

I studied with Gary and he had a big impact on my poetry, which I’ve written about elsewhere on this blog.

You won’t find traces of his influence in my work, stylistically at any rate; rather you’ll find it in my deep engagement of nature, in how I pay attention, and “be crafty and get the work done.”

Happy birthday Gary!

Here is Gary Snyder’s poem, “Old Bones”:

Old Bones

Out there walking round, looking out for food,

a rootstock, a birdcall, a seed that you can crack

plucking, digging, snaring, snagging,

barely getting by,

no food out there on dusty slopes of scree—

carry some—look for some,

go for a hungry dream.

Deer bone, Dall sheep,

bones hunger home.

Out there somewhere

a shrine for the old ones,

the dust of the old bones,

old songs and tales.

What we ate—who ate what—

how we all prevailed.

–Gary Snyder

And here is a recording of Gary reading “Old Bones”:

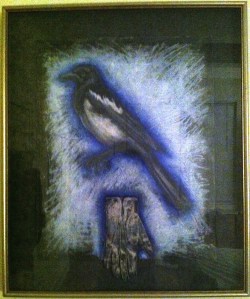

Magpies, Alaska, and my poem “Naming”

July 9, 2010

Almost a decade ago, the Alaska Quarterly Review published a poem of mine called “Naming.” I thought of it today because a good friend mentioned it in a message to me on Twitter. (She had overheard a conversation about magpies I was having with another friend.)

I’m not around magpies much these days, living on the East Coast. I miss them. Magpies, all corvids, really, are a totem for me (bears, especially polar bears are my other totem). Highly intelligent birds with bad reputations, they are a lot of fun.

Gary Snyder once told me and a group of other students that we should find totems for our poetry, “this is the world of nature, myth, archetype, and ecosystem that we must all investigate.” He also told us to “fear not science,” to know what’s what in the ecosystem, to study mind and language, and that our work should be grounded in place. Most of all, he instructed, “be crafty and get the work done.”

Advice that also, curiously enough, reminds me of magpies.

Here is my poem “Naming”:

The way a name lingers in the snow

when traced by hand.

The way angels are made in snow,

all body down,

arms moving from side to ear to side to ear—

a whisper, a pause;

the slight, melting hesitation–

The pause in the hand as it moves

over a name carved in black granite.

The “Chuck, Chuck, Chuck,”

of great-tailed grackles

at southern coastal marshes,

or the way magpies repeat,

“Meg, Meg, Meg”–

The way the rib cage of a whale

resembles the architecture of I. M. Pei.

The way two names on a page

separated by thousands of lines,

pages, bookshelves, miles, can be connected.

The way wind hums through cord grass;

rain on bluestem, on mesquite–

The tremble in the sandpiper

as it skitters over tidal mudflats,

tracking names in the wet silt,

silt that has been building

since Foreman lost to Ali,

since Troy fell — building until

we forget names altogether–

The way children, who know only

syllables endlessly repeated,

connect one moment to the next by

humming, humming, humming–

The way magpies connect branches

into thickets for their nesting–

The curve of thumb as it caresses

the letters in the name of a loved one

on the printed page, connecting

each letter with a trace of oil

from fingerprint to fingerprint,

again and again and again—

Scott Edward Anderson

Alaska Quarterly Review, Summer 2001

Here is an Mp3 recording of me reading “Naming” Live at the Writers House, University of Pennsylvania, on September 22, 2008: Scott Edward Anderson’s “Naming” (Note: there is a 10-second delay at the beginning of the file.)

Postscript: And here is a filmpoem of “Naming” made by Alastair Cook in 2011: Naming

5 Books of Contemporary Poetry I Can’t Live Without

March 23, 2010

Thanks to Peter Semmelhack, who asked for poetry recommendations via Twitter, I made a list of the 5 books of “contemporary” US poetry I can’t live without:

Elizabeth Bishop, Geography III

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)