My friend and colleague Leonor Sampaio da Silva published her first collection of poems last summer, Quase um Carimbo (Companhia das Ilhas, 2022).

Born on the island of São Miguel, Azores, Leonor holds a master’s degree in Anglo-Portuguese Studies from the Universidade Novo de Lisboa and a PhD in Anglo-American Studies from the University of the Azores, where she has taught since 1991.

Having published a number of academic papers and contributions to various books, anthologies, and literary magazines, Leonor made her literary debut with a book of short stories, Mau Tempo e Má Sorte – contos pouco exemplares, which received the Daniel de Sá Humanities Prize in 2014. She is also the author of ABN da Pessoa com Universo ao Fundo (2017) and, with Carlos Carvalho, Pouca Terra – Fotografia e Literatura (2019).

“My idea for [this] book was to talk about the experience of isolation caused by the pandemic,” Leonor explained to me. “In which we lost contact with others and forced ourselves to face situations such as the vulnerability of life, how to make sense of each day, how to live with routine.”

Some of the poems read like diary entries, the poetic voice spoken by characters representing, as Leonor notes, “the others that exist within and outside of oneself.”

“Carimbo,” it may be useful to note, means “stamp,” the kind used to mark or authenticate official or private papers. Another meaning of the word, however, is “timestamp” (although usually written as “carimbo de data/hora.”) and, in this collection, each poem is marked by a timestamp: morning, afternoon, or night, as well as an action–I wake up, I sit down, I get up–as if to indicate stage direction.

It’s as if the characters in the poems are actors in their own play, marking their time, the pandemic imbuing even the most mundane tasks with the aspects of a theatrical production.

The book title translates as “Almost a Stamp,” which leads the reader to a question: if it is “almost,” what is it? An approximation? What is reality? The questions are heightened by the ending of the book where the theatrical stage suddenly becomes cinematic, play becomes film, language shifts in tone, the curtain falls, a wind picks up, a torrential rain pours down, and fallen leaves return to their trees. The speaker remains lonely. The book ends with one last action: “Adormeço” (I fall asleep).

“Poetry,” Leonor argues, “is a way of putting us in touch with each other and exploring new languages.” She carries this thread throughout the collection, whether using “the more intimate language of the diary/newspaper” or “the more social language of the theater,” demonstrating that “everything happens as if on a stage” and shielding us from loneliness and death.

Quase um Carimbo is an impressive debut poetry collection and I hope to translate more of it in the future.

Here are two poems by Leonor Sampaio da Silva in the original Portuguese and my translations into English:

manhã

acordo

uma personagem pragueja baixinho

pela noite mal dormida

o que farei se um Comboio transformar

a geografia deste lugar?

pensar no improvável tem sido

passatempo habitual

quase uma Obsessão

preocupa-me em demasia

a falta de uma Estação

—

morning

I wake up

a character curses softly

over the sleepless night

what will I do if a train transforms

the geography of this place?

thinking about the improbable has been

a regular hobby

almost an obsession

it worries me too much

the lack of a station

________

manhã

acordo

deve estar um dia quente a avaliar pela

temperatura do quarto

o corpo, o que é um corpo?

uma madeixa cortada

vivendo por um fio

enquanto aguarda reunir-se

à cabeça que dela se esqueceu

uma madeixa que se deixa

varrer

alisar

torcer em caracol

alourar ao sol

o sol, o que é o sol?

um corpo

—

morning

I wake up

it must be a hot day judging by

the temperature of the room

a body, what is a body?

a severed lock

living by a thread

while waiting to be reunited

with the head that has forgotten it

a lock that lets itself

sweep

smooth

twists into a curl

glistening in the sun

the sun, what is the sun?

a body

–Leonor Sampaio da Silva, from Quase um Carimbo

(translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson)

___

Speaking of the island of São Miguel: I am excited to host a Writing Retreat there from 13-18 October 2023! Join me for 5 days of writing and immersion in the nature, food, and culture of the Azores. We’ll explore the island, focus with deep attention, expand our horizons, and tap into the stories within. Details and registration at https://www.scottedwardanderson.com/azores-retreat

My Year in Writing: 2022

November 28, 2022

Now is the time, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing. It’s been a pretty productive year, considering it also included a move from Brooklyn to the Berkshires:

Published Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations (Shanti Arts)

Book launch for Wine-Dark Sea online with Kathryn Miles (Feb)

Appearance on Portuguese American Radio Hour with Diniz Borges (March)

World Poetry Day/Cagarro Colloquium reading (March)

Book launch with Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (March)

Book signing at Terrain.org booth at #AWP22 in Philadelphia (March)

Wine-Dark Sea gets “Taylored” by @taylorswift_as_books on Instagram! (March)

Lecture at University of the Azores: Mesa-redonda Poesia, Tradução e Memória (April)

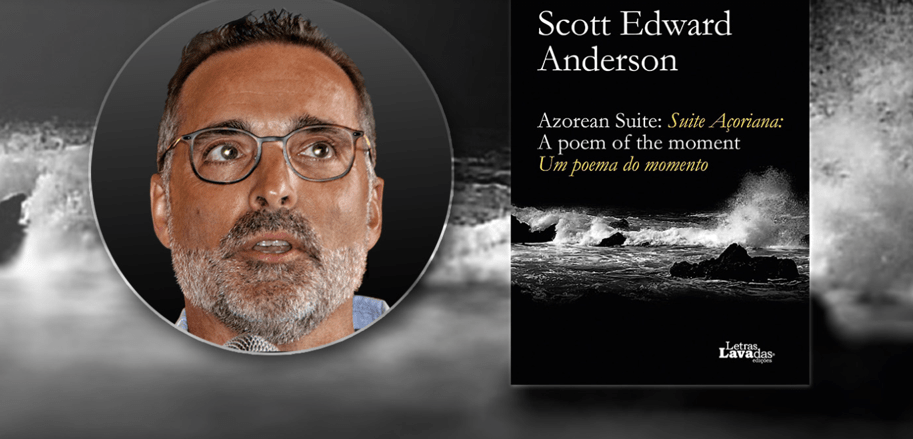

Azores launch for Wine-dark Sea and Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana at Letras Levadas in Ponta Delgada, São Miguel, Azores, with Leonor Sampaio Silva (April)

Açores Hoje television interview with Juliana Lopes on RTP Açores (April)

Terrain.org Reading Series with Joe Wilkins and Betsy Aoki (April)

“Phase Change” and “Under the Linden’s Spell” reprinted in TS Poetry’s Every Day Poems (online/email)

“Midnight Sun” and “Shapeshifting” reprinted in Earth Song: a nature poems experience (anthology), edited by Sara Barkat and published by TS Poetry Press

Named Ryan Observatory’s first Poet Laureate

Mentored 2 students in Creative Nonfiction for Adroit Journal Summer Mentorship Program (June/July) [UPDATE: one of the students I mentored got accepted into the University of Pennsylvania, early decision! So proud of her!]

Translated Pedro da Silveira’s A ilha e o mundo, his first book of poems (1952)

Excerpts from Corsair of the Islands, my translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s Corsário das Ilhas, published in Barzakh Magazine (online) (August)

Panelist/presenter at Colóquio: Pedro da Silveira – faces de um poliedo cultural, University of the Açores: On Translating Pedro da Silveira’s A Ilha (September)

Lançamento da obra Habitar: um ecopoema, Margarida Vale de Gato’s translation of Dwelling: an ecopoem, published by Poética Edições, with Nuno Júdice, Luís Filipe Sarmento, and Margarida Vale de Gato, at FLAD in Lisbon (September)

Guest lecturer in Creative Writing at University of the Azores (Leonor Sampaio Silva, professora)

Panelist/presenter at 36th Colóquio da Lusofonia, Centro Natália Correia, Fajã de Biaxo, São Miguel, Azores: reading from Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana with Eduardo Bettencourt Pinto (October)

#YeahYouWrite Catskill Reading at Fahrenheit 451 House, Catskill, NY w/Stephanie Barber, Laurie Stone, and Sara Lippmann (October)

Guest Writer at UConn Stamford creative writing class (Mary Newell, professor) (October)

Poet & Astronomer in Conversation (with Derrick Pitts, Chief Astronomer of the Franklin Institute) at Ryan Observatory at Muddy Run, PA (November)

“Wine-Dark Sea” (poem) published in American Studies Over_Seas (November)

20th Anniversary of residency at Millay Arts and writing of Dwelling: an ecopoem (November) [UPDATE: Got asked to join the Board of Millay Arts in December.]

Selections from Habitar: um ecopoema published in Gávea-Brown (US) and Grotta (Azores)

Book reviews in Gávea-Brown and Pessoa Plural [Postponed until 2023.](December)

My essay, “Açorianidade and the Radiance of Sensibility,” accepted by Barzakh Magazine for publication in Winter 2023 issue. (December)

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.”

Like I said last year, I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

National Poetry Month 2022, Week Three: Millicent Borges Accardi’s “The Graphics of Home”

April 20, 2022

When Samantha and I were back in São Miguel two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to place a plaque at Emigrant Square in honor of my great-grandparents José and Anna Rodrigues Casquilho, who emigrated from the Azores in 1906. As the wind whipped up on the plaza, swirling around the large mosaic globe, and the ocean waves crashed against the rocky north shore, I had the distinct impression my bisavós were making their presence known.

The ceremony was emotional for me, especially because several members of my Azorean family attended. I delivered a speech in Portuguese—although much of it may have been lost on the wind—and placed the plaque in the square that had been reserved for it. I couldn’t help thinking of my bricklayer great-grandfather when I nestled the plaque into the fresh mortar.

(Coincidentally, outside Letras Lavadas Livraria the night before, where we were launching my books Azorean Suite and Wine-Dark Sea, stone workers were busy replacing the basalt and limestone calçadas and street paving stones right up until we started talking—another sign that my great-grandfather was present.)

This got me thinking about other emigrants from the islands and about Millicent Borges Accardi’s new book of poetry, Through a Grainy Landscape, which, as another Azorean American writer, Katherine Vaz, puts it, explores “what heritage means to those descended from immigrants long established in the place of their dreams.”

Accardi’s books include Only More So (Salmon Poetry, 2016) and she has received a Fulbright, along with fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), CantoMundo, the California Arts Council, Yaddo, Fundação Luso-Americana (FLAD), and the Barbara Deming Foundation. She lives in Topanga, California, and has degrees in writing from CSULB and USC. In 2012, Accardi started the “Kale Soup for the Soul” reading series featuring Portuguese-American writers.

Here is Millicent Borges Accardi’s “The Graphics of Home”

Were broken by the Great

Depression, the textile mills,

and the golf ball factories.

We came from The Azores

and the mainland and Canada,

settling in Hawaii and New Bedford

and San Pedro, the original

Navigators. No one was documented.

Here was what I learned at home

thru the lifecycle of a shirt.

Polyester and cotton, it arrived

in the mail, from Sears,

sent as a hand-me-down

from Fall River, carefully washed

and ironed and pressed,

in a tomato box that had been

repurposed and wrapped in brown

paper and smelling of stale

cigarettes. That shirt was worn

and washed and used many times,

as if it had been new. When they

frayed, the elbows were mended

and torn pockets were reconnected

with thick carpet-makers’ thread.

When the sleeves were too worn

to restore, they were scissored

off to make short sleeves and then

the new ends were folded and hemmed

until no more and then there was the time

when the sleeves were cut off

entirely, to create a summer top

or costume for play time, sleeveless,

perhaps a vest for a pirate.

When outgrown and too worn

for even that, the placket of buttons was removed,

in one straight hard cut along the body

of the shirt front, through and through.

The buttons were pulled off by hand,

for storage in an old cookie tin,

the cloth cut into small usable pieces

for mending, for doll clothes, for

whatever was left over. The rest, torn

into jagged rags for cleaning and, if the fabric was soft,

used for Saturday’s dusting of the good furniture

in the den. Whatever was left, was sold

by the pound, wrapped and rolled into

giant cloth balls, sold to the rag man

who made his rounds in the neighborhood

all oily and urgent and smiling as if

his soul were a miracle of naturalized

birth.

From Through a Grainy Landscape by Millicent Borges Accardi, New Meridian Arts (2021)

Photo by Ana Cristina Gil, University of the Azores.

My apologies for not being on top of my game with regards to National Poetry Month Mailings this year. Samantha and I just returned from an emotional trip to our beloved island of São Miguel, in the Azores, after two years away.

It was emotion-filled not only because the pandemic kept us way for two years—we had tried to go back as recently as December, but Omicron dissuaded us—but because in the interim years we had determined that we want to divide our time between there and our new home in the Berkshires and this trip solidified and confirmed that plan.

On top of that, we held a ceremony to place a plaque at the Praça do Emigrante (Emigrant Square) honoring the memory and sacrifice of my two great-grandparents who emigrated from the island in 1906. Joining us were cousins from my family there, the Casquilho family, along with the director and staff from the Associação dos Emigrantes Açorianos.

It was a windy afternoon, and the waves were crashing against the rocky shore along the north coast of the island, as if the spirit of my great-grandparents were making their presence known.

All this to say that I’m behind in my weekly mailings and I apologize. This week, I’m going to share post one of my translations of the great Azorean poet Vitorino Nemésio, “Ship,” which I hope you will enjoy. It originally appeared in Gávea-Brown Journal and was reprinted in my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. Here it is in the original Portuguese and in my translation:

Navio

Tenho a carne dorida

Do pousar de umas aves

Que não sei de onde são:

Só sei que gostam de vida

Picada em meu coração.

Quando vêm, vêm suaves;

Partindo, tão gordas vão!

Como eu gosto de estar

Aqui na minha janela

A dar miolos às aves!

Ponho-me a olhar para o mar:

—Olha-me um navio sem rumo!

E, de vê-lo, dá-lho a vela,

Ou sejam meus cílios tristes:

A ave e a nave, em resumo,

Aqui, na minha janela.

—Vitorino Nemésio, Nem Toda A Noite A Vida

___

Ship

My flesh is sore

from the landing of some birds

I don’t know where they’re from.

I only know that they, like life,

sting in my heart.

When they come, they come softly;

leaving, they go so heavy!

How I like to be

here at my window

giving my mind over to the birds!

I’m looking at the sea:

look at that aimless ship!

And, seeing it, give it a lamp[i],

or my sad eyelashes:

the bird and the ship, in a nutshell,

here, at my window.

—translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

[i] For “vela,” I like “lamp” here, rather than “candle” or “sail,” because it echoes the idea of lighting a lamp to draw in a weary traveler—although I think “salute” or “sign” might also work, although not technically accurate. Also “lamp” hearkens back to Nemésio’s stated desire, expressed in his Corsário das Ilhas, which I’ve been translating for Tagus Press, of wanting to be a lighthouse keeper.

WINE-DARK SEA BOOK LAUNCH & READING

March 2, 2022

In conversation with Kathryn Miles

On #pubday eve, Kathryn Miles and I got together to chat about my new book, Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations. We had a wide-ranging conversation about the book, specific poems, finding love at middle age, the idea of home, and the Azores — and I even read a poem in Portuguese.

Have a look here:

The book came out March 1st and is available through the links on my website: scottedwardanderson.com/wine-dark-sea

My Year in Writing: 2021

November 24, 2021

Now is the time of year, between my birthday and the end of the year, when I take stock of my year in writing.

What a year it’s been, deepening my connections to my ancestral homeland of the Azores, as well as my ties to the diaspora throughout North America. Here we go:

- Signed contract with Shanti Arts for Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations to be published in Spring 2022. (Technically signed this at the very end of 2020, but thought it was worth mentioning again.)

- Published “Five Poems by Vitorino Nemésio” in my English translations in Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies.

- Interview and review by Esmeralda Cabral appeared in Gávea-Brown and was later translated into Portuguese by Esmeralda and Marta Cowling and appeared in Diário dos Açores.

- Published four translations by Margarida Vale de Gato from Dwelling in Colóquio/Letras by the Gulbenkian Foundation. And signed contract with Poética Edições for Habitar: uma ecopoema, translation by Margarida of my book Dwelling: an ecopoem. Received funding for Margarida’s translation from FLAD.

- Associação dos Emigrantes Açorianos AEA video presentation, “Açores de Mil Ilhas” for World Poetry Day.

- Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana review by Maria João Covas (video); and translation of Vamberto Freitas’s (2020) review published in Portuguese-American Journal.

- Wrote a poem in português for Letras Lavadas’s celebration, Dia Internacional da Mulher. Here is the video presentation, which includes the fabulous Aníbal Pires reading my poem, “A outra metade do céu/The other half of the sky.”

- Talk for New Bedford Whaling Museum on “Azorean Suite: A Voyage of Discovery Through Ancestry, Whaling, and Other Atlantic Crossings”

- Dwelling featured in a class at Providence College on Environmental Philosophy, thanks to Professor Ryan Shea; spent a week there, including teaching three classes and giving a reading/talk at the PC Humanities Forum.

- Readings: RONDA: Leiria Poetry Festival (March); Filaments of Atlantic Heritage (March), Cravos Vermelhos Oara Todos os Povos/World Poetry Movement Reading (April); A Nova Revolução dos Cravos (April), Cagarro Colloquium—Azores Day & launch (May); ASLE Spotlight Series (June); Juniper Moon’s Sunday Live reading series (August), LAEF Conference/PBBI (October); and A Voz dos Avós Conference/PBBI (November). Phew, I’m exhausted just writing that schedule!

- Translated poems by Luís Filipe Sarmento, Ângela de Almeida, and Adelaide Freitas.

- Panelist for PALCUS on Embracing Modern Portuguese Culture (spoke about Cagarro Colloquium, translation, etc.).

- Participated in “Insularity and Beyond: The Azores & American Ties” webinar with University of the Açores.

- Participated in session with Margarida Vale de Gota’s translation students at University of the Lisbon via Zoom.

- Recorded a video—em português—for Letras Lavadas’s second anniversary of bookstore in PDL

- Finished a draft of my translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s Corsário das Ilhas and revisions corresponding to new (2021) Portuguese edition.

- Published my talk from PC Humanities Forum in Gavéa-Brown.

- Published “Wine-Dark Sea” (poem) in America Studies Over_Seas.

- Published two poems, “The Pre-dawn Song of the Pearly-eyed Thrasher” and “Under the Linden’s Spell,” in The Wayfarer.

- Published “Phase Change” (poem) in ONE ART (online poetry journal).

- Scrapped portions of my work-in-progress, The Others in Me, after consulting with two writer friends about it, but found a new approach through working with Marion Roach Smith, which I will start in 2022…

What a year! I am exceedingly grateful to everyone who has supported my writing over the past year. As Walter Lowenfels wrote, “One reader is a miracle; two, a mass movement.” I feel like I’ve been blessed by a mass miracle this year!

Please join me this Thursday, 3 June, at 7PM EDT, for a reading and talk I’m giving for the New Bedford Whaling Museum, which focuses on the connections between the Azores, New Bedford, and Rhode Island, whaling, and other Atlantic Crossings.

Inspired by my explorations into my family heritage, which in turn inspired my book-length poem Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana, this reading and talk will explore the journeys of various waves of immigrants to America and their connection across the Atlantic to the Azores.

I’ll share passages from Azorean Suite, as well as from my work-in-progress, a research-driven memoir called “The Others in Me: A Journey to Discover Ancestry, Identity, and Lost Heritage.”

The ZOOM event is past, but you can watch the video here: Whaling Museum

Hope to “see” you there!

National Poetry Month 2021, Bonus Week: My translation of Vitorino Nemésio’s “A Árvore do Silêncio”

May 2, 2021

For my bonus post this year, wrapping up this Poetry Month featuring poets of the Azores and its Diaspora, I want to share one of my translations of the great 20th Century Azorean poet Vitorino Nemésio. (This translation appears in the current issue of Gávea-Brown: A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, along with four others.)

Photo by Manuel de Sousa, Creative Commons License

A poet, essayist, and public intellectual, Nemésio was born on Terceira Island in 1901 and is best known for his novel Mau tempo no canal (1945), which was translated into English by Francisco Cota Fagundes and published as Stormy Isles: An Azorean Tale.

In 1932, the quincentennial year of Gonçalo Velho Cabral’s “discovery” of the Azores, Nemésio coined the term “açorianidade,” which he would explore in two important essays, and which would become the subject of much debate over the years. There are those who see the term as somewhat limiting: describing as it does a specific, fixed set of qualities of the island condition—insularity, for example—that belies a greater dynamism in the spirit of the islanders.

Nevertheless, I think its usefulness as a term is somewhat expanded when we look at what Nemésio himself said about it, reflecting the entirety of his term rather than one dimension of it. Instead of limiting it as a descriptor to what it’s like to be born on the islands, Nemésio asserted that it was appropriate, too, for those who emigrated from the islands, as well as those who later returned. (And, by extension, as I said in a recent interview, I like to think he intended it to continue through or beyond the generations.)

The term, wrote Antonio Machado Pires in his essay, “The Azorean Man and Azoreanity,” “not only expresses the quality and soul of being Azorean, inside or outside (mainly outside?) of the Azores, but the set of constraints of archipelagic living: its geography (which ‘is worth as much as history’), its volcanism, its economic limitations, but also its own capacity as a traditional ‘economy’ of subsistence, its manifestations of culture and popular religiosity, their idiosyncrasy, their speaking, everything that contributes to verify identity.”

As a “warm-up exercise” for translating Nemésio’s travel diary, Corsário das Ilhas (1956), for which I am currently under contract with Tagus Press of UMass Dartmouth (with financial support from Brown University), I started with some of his poems. And I hope to continue with more, because Nemésio is worthy of a larger audience here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief tour of some of the poetry of the Azores and its Diaspora.

Here is Vitorino Nemésio’s “A Árvore do Silêncio” and my translation, “The Tree of Silence”:

A ÁRVORE DO SILÊNCIO

Se a nossa voz crescesse, onde era a árvore?

Em que pontas, a corola do silêncio?

Coração já cansado, és a raiz:

Uma ave te passe a outro país.

Coisas de terra são palavra.

Semeia o que calou.

Não faz sentido quem lavra

Se o não colhe do que amou.

Assim, sílaba e folha, porque não

Num só ramo levá-las

com a graça e o redondo de uma mão?

(Tu não te calas? Tu não te calas?!)

—Vitorino Nemésio de Canto de Véspera (1966)

_____________

THE TREE OF SILENCE

If our voice grew, where was the tree?

To what ends, the corolla of silence?

Heart already tired, you are the root:

a bird passes you en route to another country.

Earthly things are word.

Sow what is silent.

It doesn’t matter who plows,

if you don’t reap what you loved.

So, why not take them,

syllable and leaf, in a single bunch

with the graceful roundness of one hand?

(Don’t you keep quiet? Don’t you keep quiet?!)

—translated from the Portuguese by Scott Edward Anderson

from Gávea-Brown—A Bilingual Journal of Portuguese-North American Letters and Studies, vol. 43. Brown University, 2021

National Poetry Month 2021, Week Four: Adelaide Freitas’s “In the Bulge of Your Body”

April 30, 2021

Continuing to explore the poets and poetry of the Azores and its Diaspora, this week I’m featuring a poem by the late Adelaide Freitas, a wonderful Azorean poet, novelist, and essayist deserving of more attention.

Freitas was born 20 April 1949 in Achadinha, on the northeastern coast of São Miguel Island. She attended school in Ponta Delgada before moving with her family to the United States, where she attended New Bedford High School in Massachusetts. In 1972, she graduated with a BA in Portuguese from the Southeastern Massachusetts University (now UMass Dartmouth) and went on to earn a master’s degree in Comparative Literature from the City University of New York and a PhD in American Literature from the University of Azores. She lived in Ponta Delgada with her husband, Vamberto Freitas, and was a professor of American Literature and Culture at the University of the Azores.

In 2018, Adelaide Freitas was honored by the Legislative Assembly of the Autonomous Region of the Azores with the Insígnia Autonómica de Reconhecimento (Commendation of Recognition), just a few weeks before she passed away after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.

“Adelaide Freitas had gone silent years ago through the devastation of illness,” wrote one of her translators, Emanuel Melo, on his blog. “Her husband, Vamberto Freitas, himself a man of letters and important literary critic in the Portuguese diaspora, with enduring love and faithfulness kept her by his side, even writing about her, but above all loving her with steadfastness. In one of his blog posts he wrote how in the middle of a sleepless night, with her resting in the next room, he would take her books from the shelf and read her words to himself when he could no longer her the voice of his beloved wife.”

Her novel, Smiling in the Darkness, is an intimate portrait of what life was like on the Azores during the latter half of the 20th Century, and follows a young woman who struggles with the absence of her emigrant parents—who left her behind when they went to America—and her desire to explore the world beyond her island home. It was recently published in a translation by Katherine Baker, Emanuel Melo, and others. You can order a copy (and you should) from Tagus Press here: Smiling in the Darkness.

Here is her poem, “No bojo do teu corpo” in its original Portuguese and my English translation:

“No bojo do teu corpo”

No bojo do teu copo

olho translúcido o teu corpo

Vibra a alegria da tua emoção

e em mim se dilui a sua gota

Ballet agita o copo

treme a boca da garrafa

A mão abafa o vidro morno

cala-se enterrada a ternura dos lábios

A folha verde voa etérea

pousa no líquido desfeito

Dela nasce uma flor

e o mundo nela se espelha

branca a luz se intersecta

refrecta o whisky beijado

Guardanapo assim molhado

refresca a tua fronte

Gentil ela se inclina

no Outro se confunde

No tchim-tchim da efusão

treme bojo do teu corpo

—

“In the bulge of your body”

In the bulge of your glass

I see your translucent body

Vibrating with the joy of your emotion

and your drop dissolves in me

Ballet stirs the glass

the mouth of the bottle is trembling

The hand stifles the tepid glass

the tenderness of the lips is buried, remains silent

The green leaf flies ethereal

lands in the dissolved liquid

From it a flower is born

and the world is mirrored in it

white light intersects

refracting the whisky kiss

Such a wet napkin

refreshing your brow

Gently she leans

into the Other, gets confused

In the Tchim-tchim![1] of effusion

the bulge of your body trembles

—Adelaide Freitas (translated by Scott Edward Anderson)

[1] Tchim-tchim! is an expression like Cheers! An onomatopoeic phrase that connotes the clinking of glasses. I decided not to translate it here, although I could have gone with “cling-cling!” or something similar.

Jardim Botânico José do Canto, Ponta Delgada, Azores. Photo by SEA

I first encountered Logan Duarte through Christopher Larkosh’s “Writing the Moment Lusodiasporic” event last June. A two-day event sponsored by the College of Arts and Sciences and the UMass Dartmouth Department of Portuguese, it brought together Luso-North American writers from throughout Canada and the U.S.

The event was originally supposed to be held in April at the Casa da Saudade Library in New Bedford, but due to the pandemic, it was moved to Zoom in June. The event featured a combination of presentations by writers and cultural agents like Irene Marques, Humberto da Silva, and Emanuel Melo, along with a generative writing workshop led by Carlo Matos.

(Larkosh, who tragically died this past December, served as Logan’s professor and adviser at UMass Dartmouth, and I’d like to dedicate this post to his memory.)

I next saw Logan when we both read for Diniz Borges’ Filaments of the Atlantic Heritage symposium in March 2021. I was impressed with Logan’s poetry, enthusiasm, and scholarship.

One of the poems Logan read during that session was “My Statue,” which he described to me as, “an act of homage towards a man who is the lifeblood of my açorianidade, and a testament to those who have gone before; those whose presence grows stronger in physical absence and gives us the confidence to smile in the rain.”

Logan is an Azorean Portuguese American writer currently based in Taunton, Massachusetts. His family came from São Miguel Island in the 1960s, which makes him first generation American; although he sometimes jokingly refers to himself as “0.5 generation,” having called Lisbon, Portugal, his home for part of his life.

His writing centers around cultural identity in the Luso-American diaspora and has been a runner-up for the Disquiet International Literary Program’s Luso-American Fellowship (2019) and featured in the Legacy section of the Tribuna Portuguesa (2020). He has a forthcoming set of poems in the upcoming issue of Gávea-Brown, a bilingual journal of Portuguese American letters and studies published by Brown University.

Logan is expected to graduate with a master’s in teaching from UMass Dartmouth in 2021, from which he also received his BA in Portuguese. He also studied at Universidade Católica Portuguesa and Universidade de Lisboa and has taught Portuguese at Milford and Taunton high schools and at Escola Oficial Portuguesa. He will be a graduate Teaching Fellow at UMass Dartmouth beginning his second masters in Portuguese Studies in the upcoming academic year.

Here is Logan Duarte’s “My Statue”

My Statue

Rain pelts the cobblestone calçada. A utopia turns to a warzone.

Tourists scatter…I walk

Knowing all too well the dangerous potential of a slick calçada.

Some of them slip. Now they know.

Walking, thinking, unperturbed by the hail of crossfire in which I am caught, I lift my head to see a statue.

I stop, my eyes examining its unique character.

It stands firm; the quintessence of gallantry; completely untouched by the bombardment letting loose on the city.

All else assumes a deep gray despondence, battered by the bombs that fall from the clouds. The streets are barren; a wasteland.

But the statue stands unscathed.

Only light shines on this singular obra-prima perfectly guarded in a safe corner of the universe.

A man stands chiseled out of the finest marble.

His eyes look directly at me…no one else.

Below him, a plaque:

“Ocean-crosser, storm-braver, fearless warrior”.

Who could it be?

A hero to the people? A national figure? The sacred one-eyed man?

No. This is no ordinary statue. This one is only mine.

I continue walking, still thinking. I still see a statue…

My statue…my avô.

The corners of my mouth raise nearly to my ears at the sight of my statue, and the rain clears. Tourists emerge from their hideaways; some still rubbing their bruises.

Their selfies one shade darker now,

But my statue remains unscathed.

It guides me through the warzone—a beacon amidst brume.

So that when others run, and sometimes slip,

I walk and think of my statue who in life sacrificed so much

So that I may not fear the rain.

And that I may turn my warzone into utopia.

—Logan Duarte

(This poem, used with permission of the author, originally appeared in Tribuna Portuguesa, in a slightly different version.)