Next month marks the bicentennial of Robert Browning, who was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. My Samantha recently sent me his poem “Now” and it spoke to me, although it was not familiar to me.

Browning is a bit of an enigma: simultaneously overshadowed by his more famous wife, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and lionized as one of the great creators of the dramatic monologue.

Victorian readers found his work somewhat difficult, in part because of his sometimes arcane language and obscure references. He was home-schooled and self-taught – subsequently, many of his allusions were lost on his more conventionally educated audience.

Ultimately, Browning, as Wordsworth said of all great poets, had to “create the taste by which [he was] to be enjoyed.”

One of Browning’s enduring themes was “ideal love,” which for the poet meant the consummation and culmination of an intuitive course of action wherein a pair of lovers pierce the barrier separating them to become one in an all-consuming spiritual union — the “moment eternal” between two human beings.

To Browning, the passion and intensity of romantic love was often at odds with conventional social morality. Ideal love in Browning’s conception required giving up everything, what others have called “the world well-lost for love.”

Here is Robert Browning’s short lyric poem, “Now”:

Out of your whole life give but a moment!

All of your life that has gone before,

All to come after it, — so you ignore,

So you make perfect the present, condense,

In a rapture of rage, for perfection’s endowment,

Thought and feeling and soul and sense,

Merged in a moment which gives me at last

You around me for once, you beneath me, above me —

Me, sure that, despite of time future, time past,

This tick of life-time’s one moment you love me!

How long such suspension may linger? Ah, Sweet,

The moment eternal — just that and no more —

When ecstasy’s utmost we clutch at the core,

While cheeks burn, arms open, eyes shut, and lips meet!

–Robert Browning, 1812-1889

Elegy & Exile: Elizabeth Bishop’s Poem “Crusoe in England”

February 8, 2012

All year long I’ve been celebrating the 100th anniversary of the birth of the poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979).

You can read some of what I’ve written about Ms. Bishop and her poetry on this blog.

Today, the 101st anniversary of the poet’s birth, to mark the completion of the centennial celebrations, I want to share my essay “Elegy & Exile: Elizabeth Bishop’s Poem ‘Crusoe in England’.”

Here is my essay as it appeared in The Worcester Review‘s special edition “Bishop’s Century: Her Poems and Art”:

A new volcano has erupted,

the papers say, and last week I was reading

where some ship saw an island being born

…

They named it. But my poor island’s still

un-rediscovered, un-renamable.— Elizabeth Bishop

So begins Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, “Crusoe in England” one of two fine elegies found in her last collection, Geography III, and her longest sustained narrative poem.

The island is “un-renamable,” which implies it was named by someone once. In fact, the speaker in the poem named it “The Island of Despair,” for its volcanic centerpiece, “Mont d’Espoir or Mount Despair.” He had time to play with names; twenty-eight years, by at least one account.

The speaker is, of course, the protagonist of Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel, Robinson Crusoe – and he isn’t.

Defoe’s Robinson was Christian, civilized, and strongly empirical in his thinking; Bishop’s Crusoe is skeptical and unsure of his knowledge and memory.

Both are displaced figures, but Defoe’s Robinson feels that displacement most acutely on the island upon which he is shipwrecked. Bishop’s Crusoe feels more displaced after his return to “another island,/ that doesn’t seem like one…” His home country of England.

Crusoe was lonely on the island; its clouds, volcanoes, and water-spouts were no consolation – “beautiful, yes, but not much company.” He experiences a “dislocation of physical scale,” as Bishop biographer Lorrie Goldensohn observed.

He’s a giant compared to the volcanoes, which appear in miniature from such distance; the goats and turtles, too. It is, Goldensohn writes, “an analogue of the nausea of connection and disconnection.”

Then “Friday” arrives, but even their relationship, in the Bishop poem, is tinged with loneliness. They both long for love they cannot consummate, “I wanted to propagate my kind,/ and so did he, I think, poor boy.”

Defoe’s Robinson is much less isolated. His island is visited by native cannibals who take their victims to the island to be eaten (Friday is their prisoner; until Crusoe saves him and names him), as well as Spaniards, and English mutineers. This last group helps Robinson return to England with Friday. There are other adventures in the novel, including a voyage to Lisbon and a crossing of the Pyrenees on foot.

None of this is for Bishop. Her goal was not to re-write the novel, but to re-imagine the story. Her Crusoe possesses, as C.K. Doreski has noted, “a weary tonality of such authenticity her character seems not an extension of Defoe’s fictional exile, but a real Crusoe, endowed with a twentieth-century emotional frankness.”

Bishop’s Crusoe finds even deeper loneliness back “home,” with its “uninteresting lumber.” Once there, he longs for the intensity of life on his island, its violence and self –determination, and its objects full of meaning.

“Disconcertingly,” as Goldensohn describes it, “Crusoe discovers that the misery from which he so willingly fled was the chief stock of his life.”

Defoe’s Robinson returns to England to find nothing there for him. Robinson’s family thought him dead after his 28-year absence, and there is no inheritance for him, no fortune to claim, no home.

Crusoe, in Bishop’s devising, also finds nothing for him at home, despite the longing he felt for it while a castaway. His loss is a spiritual and cultural loss.

While on the island, he tries to hold onto his home culture. He makes “tea” and a kind of fizzy fermented drink from berries he discovers, even a homemade flute with “the weirdest scale on earth.”

Alas, he doesn’t remember enough of his culture’s great literature to make him feel at home,

The books

I’d read were full of blanks;

the poems – well, I tried

reciting to my iris beds,

“They flash upon that inward eye,

which is the bliss…” The bliss of what?

One of the first things that I did

When I got back was look it up.

The bliss is, of course, “solitude,” which is the word completing this line from Wordsworth’s “Daffodils” (” I wandered lonely as a cloud…”). We forgive Bishop this anachronism; Wordsworth’s poem was written over one hundred years after Defoe’s novel. By referencing this line she creates a sense of displacement or dislocation in us, her readers.

For Bishop’s Crusoe, solitude approaches bliss by way of banality, especially when he reflects on what was lost – including Friday, who was introduced with the banal phrase, “Friday was nice and we were friends.”

The potency of their relationship is merely hinted at; perhaps reflecting Bishop’s own sense of decorum in matters personal. (“Accounts of that have everything all wrong,” Bishop writes.)

Some critics have suggested that Friday in this poem is a stand-in for Lota de Soares Macedo, Bishop’s Brazilian lover; while others, James Merrill among them, wondered why Bishop couldn’t give us “a bit more about Friday?”

For almost as soon as Friday arrives they are taken off the island. By the end of the poem, we learn that Friday died of measles while in England, presumably a disease to which he had no immunity.

Bishop began writing “Crusoe in England” in the early 1960s – although notebook entries from 1934 hint that the poem may have its origins in her time at Vassar – and picked it up again after Lota’s death in 1967. (Goldensohn postulates based upon her reading of drafts of the poem that Bishop brought Friday into the poem at that time.)

She worked on it again after a visit to Charles Darwin’s home in Kent. She relied on Darwin’s notes from the Galapagos for her depiction of the island, along with Herman Melville’s “Encantadas,” and perhaps Randall Jarrell’s “The Island,” as has been suggested, as well as on her own experience of tropical and sub-tropical locales.

By the time she visited Galapagos in 1971, however, the poem had been delivered to The New Yorker. She must have been fairly pleased that her description was almost spot-on. (My own experience of the Galapagos has the spitting and hissing she writes about coming from the iguanas rather than the turtles, but no matter.)

Bishop’s friend and fellow poet, Robert Lowell, thought “Crusoe” to be “maybe your very best poem,” and I’m inclined to agree. (Although the poem preceding it in 1979’s Geography III, “The Waiting Room,” gives it a run for my money.)

“An analogue to your life,”Lowell wrote in a letter to Bishop, “or an ‘Ode to Dejection.’ Nothing you’ve written has such a mix of humor and desperation.”

It’s true this poem has a kind of desperation to it that comes from desolation and longing, for “home,” in particular, be it the island or England. Bishop’s humor is evident, too, in such lines as

What’s wrong about self-pity, anyway?

With my legs dangling down familiarly

over a crater’s edge, I told myself

“pity should begin at home.” So the more

pity I felt, the more I felt at home.

“By making [Crusoe’s] life center around the idea of home,” writes biographer Brett Millier, Bishop “brings him in line with her own habitually secular and domestic points of view.”

Crusoe was also an unwitting solitary, who reluctantly gave in to his plight. As such, he appealed to Bishop, especially in his self-reliance. He made things from what’s at hand, just as she made poems from what surrounded her. She, too, had surrendered to her “exile” in Brazil.

There’s an ungentle madness to Crusoe the solitary, which also contrasts somewhat with Defoe’s Robinson. The latter reads the Bible and becomes increasingly more religious. Bishop’s Crusoe is more pagan, painting goats with berry juice, dreaming of “slitting a baby’s throat, mistaking it/ for a baby goat,” and has visions of endlessly repeating islands where he is fated to catalog their flora and fauna.

I’m tempted to see this last reference as almost a nightmare reflection of the poet’s own self-exile and imprisonment by her style: her oft-cited gift for description, which she saw as limiting.

Regardless of whether Bishop saw herself in her Crusoe, her own removal to New England from Brazil – to Harvard’s uninteresting lumber – must have caused equal disconnection, a “dislocating dizziness,” to borrow Goldensohn’s phrase.

“When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived,” Bishop wrote to Robert Lowell in 1948. In “Crusoe in England,” she captures the loneliness, displacement, and loss of an individual set adrift in emotional isolation, which leads to a kind of post-traumatic stress syndrome.

For Crusoe, his island life seemed interminable and insufferable, only to turn romantic and desirable when the experience ended.

It seems likely Bishop was thinking of her life in Brazil with Lota, which had become increasingly strained towards the end, until the latter’s suicide, and the poet’s life thereafter. That makes this poem, along with “One Art,” from the same collection, an elegy with a depth beyond its surface.

Here is a link to the complete text of “Crusoe in England,” which includes an audio recording of Bishop reading the poem: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/177903

–Scott Edward Anderson

“Winter Into Spring” – Ya know, “Baby birds and plants blooming…”

February 1, 2012

I know it’s only February 1st, but it feels like Spring here on the eastern seaboard of the US.

Who knows what will happen when Punxsutawney Phil gets a look at the grass tomorrow morning? I doubt very much he will see his shadow.

It’s 64 degrees and sunny as I write this and earlier today I saw a robin bopping along by the train station.

My friend Leigh Scott challenged me to write a poem with the title or theme, “Winter Into Spring.”

As it happens, I already have a poem by that title, which I composed back in the late 90s upon my return to this coast from a few years in Alaska.

Here is my poem,

“Winter Into Spring”

Persephone brings life to the dead

With spring’s eternal hope,

Sharing the desires of young and old,

Partners in the revival of dreams.

Now dormant seeds awaken in the ground,

Hyacinth stirs with tender shoots,

And robin heralds the lengthening days;

Now winter’s coat floods river and marsh,

As we play at Eros with silk and lace.

–Scott Edward Anderson

“32 Facts About the Number Thirty-Two”

January 29, 2012

Twitter is a great place for poetry.

Not only is the short form of the messages (140 characters or less) conducive to the concision of the poetic craft, but the platform allows for the growth of connections and a network of poets in what is otherwise a lonely pursuit.

Twitter also allows for easier connections between writers and literary magazines.

Among the more active journals on Twitter is 32 Poems. Edited and published by poet Deborah Ager out of Hyattsville, MD, @32Poems is also is the host of the weekly “Poet Party” (#poetparty), which takes place Sunday nights (9-10 PM ET) on Twitter.

Some time ago, then associate editor Caroline Crew issued a challenge to fellow poet Twitter followers to use the number 32 in a poem.

At the prompting of Richard Fenwick, another poet I’ve gotten to know through the medium, I took up the challenge and wrote a poem called “32 Facts About the Number Thirty-Two.” The poem was published on the back of the Fall/Winter 2011 issue of 32 Poems (see photo at left).

Here is my poem, “32 Facts About the Number Thirty-Two”:

1.) 32 is not envious of 33 because it is surrounded by mystery on the back of a Rolling Rock beer bottle.

2.) 32 is the smallest number n with exactly 7 solutions to the equation [Phi] φ(x) = n.

3.) The Curtiss T-32 Condor II was a 1930s American biplane and bomber aircraft used by the U.S. Army Air Corps for executive transport.

4.) Year 32 (XXXII) was a leap year.

5.) Jesus is said to have been crucified in Year 32.

6.) The country code “32” is forBelgium. (You could call Hercule Poirot, if he weren’t fictional.)

7.) 32 is the new 23.

8.) 32 is the number of piano sonatas by Beethoven, completed and numbered.

9.) 32 degrees is the freezing point of water at sea level in Fahrenheit.

10.) There are 32 Kabalistic Paths of Wisdom. (Which is Madonna on?)

11.) 32 is the atomic number of the chemical element germanium (Ge), which is to say 32 is the number of protons found in the nucleus of its atom.

12.) 32 is the number of teeth in a full set of an adult human if the wisdom teeth have not been extracted.

13.) 32-bit is the size of a databus in bits.

14.) The Route 32 bus in Philadelphia will take you from Roxborough to CenterCity.

15.) 32 is the number of pages in the average comic book, excluding the cover wrap.

16.) Number 32 is for Shaquille O’Neal, Kevin McHale, Karl Malone, Magic Johnson, Dr. J, Sandy Koufax, Steve Carlton, Claude Lemieux, Marcus Allen, Jim Brown, and Franco Harris.

17.) There are 32 traditional counties in Ireland, which were formed between the late 1190s and 1607.

18.) “Thirty-two Short Films About Glenn Gould” is a film divided into thirty-two short films, thereby mimicking the thirty-two part structure of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations,” a recording of which Gould made famous or which made Gould famous.

19.) The thirty-two-bar form is popular especially among Tin Pan Alley songwriters and in rock & roll.

20.) “Deuce Coupe” is a slang term referring to the 1932 Ford coupe. “Little Deuce Coupe” was a pop song written in the 32-bar form by The Beach Boys.

21.) In the 32-bar form, each chorus is made up of four eight-bar sections.

22.) Some yogis believe there are 32 bars of energy running through our heads storing the electromagnetic component of all the thoughts, ideas, attitudes, decisions, and beliefs that we have ever had about anything.

23.) 32 is 40 % of 80.

24.) “Thirty-two Kilos” is a series of photographs by Ivonne Thein, in which she altered images of models to make them look anorexic, as if they weighed only 32 kilos (70 lbs.).

25.) According to the Urban Dictionary, “b-thirty-two” is one of the most dangerous and rapidly growing gangs in Bensonhurst,Brooklyn, and originally started on Bay 32nd St.

26.) I have had a 32-inch waist since 1982.

27.) By pregnancy week 32, an average baby weighs 3.75 pounds and is about 16.7 inches long.

28.) Nobody ever says “32-skidoo.”

29.) Psalm 32 begins “Blessed is he whose transgressions are forgiven, whose sins are covered.”

30.) Title 32 of the U.S. code outlines the role of the National Guard and allows members of the Guard to serve as law enforcement in their respective states.

31.) A beheaded body can make 32 steps, according to a legend involving King Ludwig of Bavaria in 1336.

32.) According to Microsoft Word, this poem is divided into 32 paragraphs, although I prefer to call them stanzas.

–Scott Edward Anderson

An Xmas Carol, Rewritten for a Secular Soul

December 17, 2011

My 8-year-old daughter came across a couple of typewritten sheets of paper in a copy of The Penguin Book of Christmas Carols, edited by Elizabeth Poston.

“What’s this Papa?” she asked. “It looks like it was printed on a typewriter.”

It was “printed” on a typewriter, as the picture to the right attests; the tiny holes marking most of the periods are also a dead give-away. To this day, I have heavy fingers on a keyboard.

The poem was my attempt to rewrite the lyrics to an old carol known as “The Holly & The Ivy,” a traditional English carol whose best known words and tune were collected by Cecil Sharp, and begin,

“The holly and the ivy,

When they are both full grown,

Of all the trees that are in the wood,

The holly bears the crown…”

The crown is the crown of thorns, which if you have ever touched a holly leaf, you know its prickly scorn. The lyrics go on to draw analogues between the red berry of the holly and the blood of Christ, the “bitter gall” of the holly’s bark with the balm of Jesus as a redeemer.

It is a curious mix of Christian and Pagan imagery. Holly was associated with the winter solstice and known to be sacred to the druids.

My version was written more closely in the style of a traditional New England take on the “Sans Day Carol,” itself a Cornish carol from the 19th century that shares much with “The Holly & The Ivy.”

I’ve always loved the tune — there’s an excellent version of it on the Chieftans’s Christmas album, The Bells of Dublin — but the lyrics struck me at the time of my version’s composition as too overtly religious for my then decidedly secular soul. So I rewrote the lyrics to celebrate the joys of the winter season.

With that complicated provenance, here is my poem

(Adapted from an early New England Christmas carol, itself an adaptation of “The Holly & The Ivy,” an English traditional carol.)

Now the holly bears a ber-ry

As white as the milk

When the snow drifts u-pon us

As bil-lowing silk.

When the snow drifts u-pon us

We are joyous for-to-be,

And the first tree in the green wood

It was the Holly. Holly. Hol — ly.

And the first treee in the green wood

It was the Holly.

Now the Hol-ly bears a ber-ry

As green as the grass

When sleds bring us cross the snow

Our journeys to pass.

When sleds bring us cross the snow

We are joy-ous for-to-be,

And the first tree in the green wood

It was the Holly. Holly. Hol — ly.

And the first tree in the green wood

It was the Holly.

Now the Hol-ly bears a ber-ry

As black as the coal

When we ga-ther wood-chopped

To stoke for us all.

When we ga-ther wood-chopped

We are joy-ous for-to-be,

And the first tree int he green wood

It was the Holly. Holly. Hol — ly.

And the first tree in the green wood

It was the Holly.

Now the Hol-ly bears a ber-ry

As blood is it red

When we smile in our sweet-good

All snug in our beds.

When we smile in our sweet-good

We are joy-ous for-to-be,

And the first tree in the green wood

It was the Holly. Holly. Hol — ly.

And the first tree in the green wood

It was the Holly.

Words by Scott Edward Anderson

Visions Coinciding: Celebrating Elizabeth Bishop’s Centenary

December 5, 2011

As readers of this blog know, 2011 marks the centenary of Elizabeth Bishop’s birth. I’ve been trying to celebrate it in as many ways as possible and get to some of the events throughout the year, as well as visiting her grave in Worcester, MA, and promoting her work on this blog and on Twitter by using #EB100.

Last week I attended Visions Coinciding: An Elizabeth Bishop Centennial Conference, organized by NYU’s Gallatin School and the Poetry Society of America.

The conference featured interdisciplinary responses to Bishop and her work, including a slide show and talk by Eric Karpeles exploring rarely seen images of Elizabeth Bishop and a screening of footage from Helena Blaker’s forthcoming documentary on Bishop’s years in Brazil.

The screening was followed by a discussion moderated by Alice Quinn, editor of Bishop’s posthumous collection Edgar Allen Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments, along with Blaker and Bishop scholars Brett Millier, Barbara Page, and Lloyd Schwartz.

Day two featured two lectures on Bishop’s relationship with Art. Peggy Samuels gave a fascinating exegesis of Bishop’s interest in and influence by the work of Kurt Schwitters and William Benton displayed slides of Bishop’s own paintings, sharing his insights on their context in modern art.

Jonathan Galassi moderated a lively discussion with the editors of recent collections of Bishop’s poetry, prose and correspondence, including Joelle Biele (Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker correspondence), Saskia Hamilton (Words In Air

, the Lowell-Bishop correspondence, and new edition of POEMS

), Lloyd Schwartz (new edition of PROSE

, as well as the Library of America edition of Bishop: Poems, Prose, Letters

), and Thomas Travisano (Lowell-Bishop correspondence).

All this was followed by a reading by NYU Gallatin students who each read a Bishop poem and one of their own by way of response and, finally, a star-studded lineup of contemporary American poets, including John Koethe, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Mark Strand reading poems by Bishop.

Poet Jean Valentine read Bishop’s translation of Octavio Paz’s “Objects & Apparitions” with the original read by Patrick Rosal. Maureen McLane read from her creative work-in-progress “My Elizabeth Bishop; My Gertrude Stein.”

This week is the opening of Elizabeth Bishop: Objects & Apparitions at the Tibor De Nagy Gallery in New York. The show comprises rarely exhibited original works by Bishop, including watercolors and gouaches, as well as two box assemblages inspired by the work of Joseph Cornell.

The exhibition also includes the landscape painting Miss Bishop inherited and that she wrote about in “Poem,” which begins

About the size of an old-style dollar bill,

American or Canadian,

mostly the same whites, gray greens, and steel grays

-this little painting (a sketch for a larger one?)

has never earned any money in its life.

Unfortunately, I’m going to miss the exhibit of her papers at the Vassar College Main Library, From the Archive: Discovering Elizabeth Bishop, which is on view until December 15th.

But there’s still time to celebrate Bishop’s centenary — until her 101st on February 8, 2012.

Juvenilia: “Snow Sleeping November”

November 19, 2011

JUVENILIA

1: compositions produced in the artist’s or author’s youth

2: artistic or literary compositions suited to or designed for the young

Origin of JUVENILIALatin, neuter plural of juvenilisFirst Known Use: 1622

As the Wikipedia entry for Juvenilia explains: “the term was first used in 1622 in George Wither‘s poetry collection Ivvenilia. Later, other notable poets, such as John Dryden and Alfred Lord Tennyson came to use the term for collections of their early poetry. Jane Austen‘s earlier literary works are also known by the name of Juvenilia. An exception to retrospective publication is Leigh Hunt’s collection Juvenilia, first published when he was still in his teens.”

One of my earliest extant poems, written when I was 15, came to my attention recently. The poem is called “Snow Sleeping November.” I was surprised by its language and resonance, although some of it seems over-written and bears too heavy an influence of Whitman, Frost, Hopkins, and perhaps Stephen Crane.

I can still see the cabin in New York’s Finger Lakes that provided its inspiration.

Here is my poem,

“Snow Sleeping November”

I realize the briskness of this November eve,

the quiet, complacency of stiff snow,

the darkness of full‑breasted snowclouds,

all of us retaining warmth

like soapstone.

My cup is full of hot water

the wood in the fire

gleams like cat’s eyes & gives-off a

sun‑like warmth‑‑radiant, welcoming.

Short days & long, frozen nights,

girding my boots

for the crisp winterchill,

wind driving drafts up my nose.

The sparkling, icy water

and trees stiff in the dead weight

of snow‑leaden branches.

Poets crawling at the clouds

pulling snow groundfast‑‑

Those November trees!

–Scott Edward Anderson

The painting is a sketch by my friend Lisa Hess Hesselgrave from my personal collection. You can see more work by Lisa at LisaHesselgrave.com

Writing for posterity may be as old as writing itself. Poets, novelists, essayists, and philosophers all write with the hope that their work will survive them — even if they deny it — living on to touch new readers in distant ages.

Writing for posterity may be as old as writing itself. Poets, novelists, essayists, and philosophers all write with the hope that their work will survive them — even if they deny it — living on to touch new readers in distant ages.

Some writers never lived to see their work gain an audience or even a small, devoted readership. Some, like Robert Browning, obsessed about it.

Alas, the quote from Walter Lowenfels that adorns this blog is a daily reminder to me of the fate of almost all of us.

How much of our writing will survive, will last, will live to find readers throughout our lifetime and beyond?

I was struck by this question twice this week.

The first was Tuesday night, having dinner with twin brother poets Dan and David Simpson. We were talking about the fact that none of the three of us had published collections of our work, despite “success” placing individual poems in journals and magazines, and the awards and accolades we’ve received over the years.

David told of an encounter with a writing mentor who reviewed his draft manuscript. The mentor suggested they each go through the script and rate the poems numerically: 1, 2, 3; then they would compare the results and see what came of it.

My friend was dumbfounded that the mentor found so few 1s among the collection — really only a few — and only a few 2s as well. The 3s weren’t even worth mentioning and probably should be discarded, suggested the mentor.

Bruised as David’s ego was by the experience, I found some solace in it.

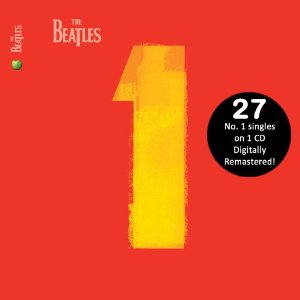

“How many #1 singles did The Beatles have?” I asked David. (27 is the answer.)

“So, okay, we can agree that none of us are The Beatles,” I offered. “But we could be, say, The Guess Who.” (That group had only had one number 1 single, “American Woman,” for three weeks May 9 -29, 1970, yet we all know the song and you probably have it streaming in your head right now at its mere mention.)

We agreed that we would be lucky to have one “hit” poem continue to be read by people after our deaths. We’d be delighted if a handful survive us, yet it’s helpful to have some perspective.

A few days later I received a request for permission to reprint a piece of writing I did in 1993. This is the most widely reprinted thing I’ve written and, I’m afraid, will likely survive any and all of my creative work.

The piece is a review of N. Scott Momaday‘s In the Presence of the Sun: Stories and Poems, 1961-1991 that I wrote for The Bloomsbury Review. I have had more requests to reprint that one 1500-word review than any other piece of writing I have done — ever.

It’s even been made available for students on such services as eNotes: Scott Edward Anderson (review date 1993).

I re-read the piece this morning — it’s not a bad piece of writing, as reviews go, and certainly lives up to eNotes’ description: “Anderson provides a thematic and stylistic review of In the Presence of the Sun.”

Yet, when I wrote the review, I never imagined it would be my most cited, most reprinted, perhaps even my most read piece of writing.

If only the strong survive may this piece rock on.

I like to listen to music when I’m making pizza. Loud music, usually cranked up as high as my computer’s external speakers will allow.

Last night, it was Nirvana’s “Nevermind,” which recently celebrated 20 years in the collective listening consciousness.

My 15-year-old son wandered into the kitchen while the last song (the hidden track), “Endless, Nameless,” filled the kitchen with sonic noise.

“What the heck is that?” he asked.

“Nirvana,” I answered, although I always thought that track sounded more like my old band Active Driveway than the rest of Nevermind.

“What’s so great about them?” he asked. I switched to the opening track, their breakthrough song “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

“Yeah, that is good,” he admitted. Then we talked about how Kurt Cobain committed suicide.

“Shotgun.”

He wanted to know why he did it. “Sometimes geniuses are so troubled they can’t cope with the pressures of life.”

Then I told him that a friend of mine, Peter Boyle, also killed himself with a shotgun five years before Cobain. Peter was an artist, too, deeply troubled — tortured even — and, like Cobain, addicted to heroin. Peter shot himself in the barn at his family’s farm; he was 37 years old. Cobain was 27. I won’t go into the significance of those ages, but you can read more here.

Peter was an amazing artist who worked in a very unusual medium: sugar. In fact, he wrote the book on blown and pulled sugar sculpting techniques, which came out the year before he died. His work had just been featured in a show, ”The Confectioner’s Art,” at the old American Craft Museum (November 1988-January 1989) in New York.

Peter tried to kill himself at least once before, that I knew about, while trying to quit heroin cold turkey. I intervened that time and suffered with him through a long night of his own personal Hell.

I wrote a poem about Peter and his suicide a some time later called “The Cartographer’s Gambit.” I changed the subject from a sugar sculptor to a cartographer; I’m not sure why, but it seemed to work.

Here is my poem, “The Cartographer’s Gambit”:

In the spindrift,

he outlines an island

for which there are no visas—

whose mapping is all too delectable,

whose charting is measured intensity.

Along these shores,

he conjures ochre bluffs, which resemble

well–turned ankles, the cleft of breast in a covescape,

and hillsides of amber light.

These are things he brought to life on paper, restless for rescue.

The uncharted territory

still gleaming in his eye—

a coastal mystery.

He lumbers, cools with the injection.

The seaboard nearly finished, dry land

his last frontier.

He reads Celine as open waters dry,

the cold spring chills him, he smokes a cigarette.

Deep within his blood, a fine line beckons—

with perfect geography.

Outside, the air is perfumed,

with a scent of powder.

Starlings prattle above him,

black, iridescent, oxymoronic:

a thousand triangles

of gun metal

fusing a jade sky.

Their opacity blinds him to reason.

Unable to move latitudinal or long,

he measures the scale of possibility,

sights his compass on true north and,

as the needle riddles the vein,

he dashes the coast with blue.

(In memoriam: Peter T. Boyle, 1952-1989)

–Scott Edward Anderson

“Midnight Sun” and Anon, the anonymous submissions magazine

September 17, 2011

I first became aware of the Scottish poetry journal Anon through some of the poets I follow on Twitter (most of whom I’ve included in my poetry list, which you can follow too here.

I first became aware of the Scottish poetry journal Anon through some of the poets I follow on Twitter (most of whom I’ve included in my poetry list, which you can follow too here.

Anon is edited by poet and social media producer Colin Fraser and Peggy Hughes, who works at the wonderful Scottish Poetry Library.

One cool thing about Anon is its format, which is reminicent of those old Penguin Classic paperbacks. The other is its completely anonymous submissions process.

The editors do not know the names of the poets whose work they are considering — and they never know the names of the poets they are rejecting. As the Anon tagline proudly proclaims it, “We don’t care who you aren’t…”

I submitted a few poems to the magazine last year, including one poem I’d written in Alaska over a dozen years before called “Midnight Sun.” The poem got picked and appeared in Anon 7.

Here’s what one reviewer, writing in the journal Sabotage, said about that issue of Anon:

“Anon Seven is an effervescent production, its poems spanning the world: from Dave Coates’ transfigured, strangely threatening ‘Leith’ (on the magazine’s doorstep, since Anon is produced in Edinburgh), to the detailed, tender surveillance of Lake Illiamna, Alaska, which Scott Edward Anderson undertakes in ‘Midnight Sun’. Its strengths lie in variety, and particularly in the sheer invention and craft of certain poems – sometimes, even, of especially successful lines, such as the opening of Richard Moorhead’s ‘I Shot A Bird’, which breaks upon the reader with a brash insistence that ‘Everyone should try some killing’.”

Here is my poem, “Midnight Sun”:

Midnight Sun

at approximately 59° 45′ N Latitude, 154° 55′ W Longitude

Each night,

I watch the sun set

over Lake Illiamna

through the willows.

How physical,

the names of willows:

Bebb and Scouler,

feltleaf, arctic, undergreen—

names ill-suited for their frail appearance.

And how palpable the story,

told by the black-capped chickadee

about the four bears who come

each night to the village,

linger for a couple of hours,

then vanish.

As the bird now vanishes

from atop the satellite dish

outside the room at Gram’s B&B.

He leaves behind

a white remembrance,

which disturbs the signal

coming from Anchorage,

interrupting a program about

the formation of the Hawaiian Islands,

and sending ripples of multi-colored “snow”

swirling into TV screen volcanoes.

While back outside,

midsummer sun barely sets on the village,

angling over sparse willows

and spruce, bentgrass and sweetgale,

perhaps twinflower, although

verifying the presence of that species

may require a second look.

A second look, which the sun

will suggest, upon its return

four and one-half hours from now.

That is when the BLM surveyors arrive

on their ATVs (whatever the weather

and whether they’re foolish or clever),

to verify yesterday’s measurements,

as they do each morning,

in this village of willows

and midnight sun.

–Scott Edward Anderson

Order copies of Anon — or better yet, a subscription — here: Anon