São Miguel, Azores, Portugal

“I don’t write to say what I think. I write to find out what I’m thinking,” said the poet Gary Snyder. To that I might add, I write to understand who I am.

Lately, I’ve been working on a project—a kind of enhanced memoir—that explores my Portuguese family history. As part of this project, I’ll be going to the Island of São Miguel in the Azores this summer, where two of my maternal great-grandparents came from, for a residency hosted by DISQUIET International, which brings together Portuguese and Portuguese-American writers.

I first started researching my Portuguese roots back in the 90s and, coincidentally, that’s when I met the Portuguese poet, Nuno Júdice. He read at Poets House, along with the translator Richard Zenith, in December of 1994.

The author of over twenty books of poems, Júdice was born in 1949, on the southern coast of Portugal, in the region known as the Algarve. He is currently a professor at Lisbon’s Universidade Nova and directs the Colóquio/Letters program for the Gulbenkian Foundation. I’m hoping to see him in Lisbon when we are on the mainland.

Here is Nuno Júdice’s “Poema” in its original and in a translation by Martin Earl.

POEMA

As coisas mais simples, ouço-as no intervalo

do vento, quando um simples bater de chuva nos

vidros rompe o silêncio da noite, e o seu ritmo

se sobrepõe ao das palavras. Por vezes, é uma

voz cansada, que repete incansavelmente

o que a noite ensina a quem a vive; de outras

vezes, corre, apressada, atropelando sentidos

e frases como se quisesse chegar ao fim, mais

depressa do que a madrugada. São coisas simples

como a areia que se apanha, e escorre por

entre os dedos enquanto os olhos procuram

uma linha nítida no horizonte; ou são as

coisas que subitamente lembramos, quando

o sol emerge num breve rasgão de nuvem.

Estas são as coisas que passam, quando o vento

fica; e são elas que tentamos lembrar, como

se as tivéssemos ouvido, e o ruído da chuva nos

vidros não tivesse apagado a sua voz.

—

POEM

It’s the simplest things that I hear in the wind’s

intervals, when the simple beating of the rain

on the windows breaks the silence of night, and its rhythm

overwhelms that of words. Sometimes, it is a

tired voice, that tirelessly repeats

what the night teaches those who live it; other

times, it runs, hurriedly, mowing down meanings

and phrases as though it wanted to reach the end, more

quickly than the dawn. We’re talking about simple things,

like the sand which is scooped up, and runs

through your fingers while your eyes search

for a clear line on the horizon; or things

that we suddenly remember, when

the sun emerges from a brief tear in the clouds.

These are the things that happen, when the wind

remains; and it is these we try to recall, as though

we had heard them, and the noise of the rain

on the windowpanes had not snuffed out their voice.

© 2006 Nuno Júdice, from As coisas mais simples, Lisbon: Dom Quixote, 2006

Translation © 2007 Martin Earl, first published on Poetry International, 2014

“Poetry As Practice,” A Craft Essay

March 24, 2018

Cleaver Magazine published my craft essay, “Poetry As Practice,” earlier this year:

POETRY AS PRACTICE

POETRY AS PRACTICE

How Paying Attention Helps Us Improve Our Writing in the Age of Distraction

A Craft Essay

by Scott Edward Anderson

In this lyrical essay on the writing life, Scott Edward Anderson shows how poetry can be more than a formal approach to writing, more than an activity of technique, but a way to approach the world, which is good for both the poet and the poem.—Grant Clauser, Editor

Walking in Wissahickon Park after dropping my twins at their school in Philadelphia, I find muddy trails from the night’s heavy rains and temporary streams running along my path. The fuchsia flowers of a redbud tree shine brilliantly against the green of early leafing shrubs. A few chipmunks scurry among leaves on the forest floor. Birdsong is all around me: I note some of the birds—if they are bright enough and close enough to the trail or I recognize their song—the red flash of a cardinal lights on a branch nearby; a robin lands on the trail ahead, scraping his yellow beak against a rock.

Observation like this helps feed my database of images, fragments of music, and overheard speech, which prepares my poetry-brain for the work of choosing words, putting them in a certain order, and forming phrases into lines, stanzas, and eventually entire poems.

Remembering a line I’m working on, I worry it like a dog with a bone, gnawing on the words, their syntax, imagery, sound or feel in my mouth and mind. Playing with the line, I’ll follow it until it leads somewhere or dumps me in a ditch, when I’ll file it away for another day. I’m paying attention to where the poem wants to go. READ MORE

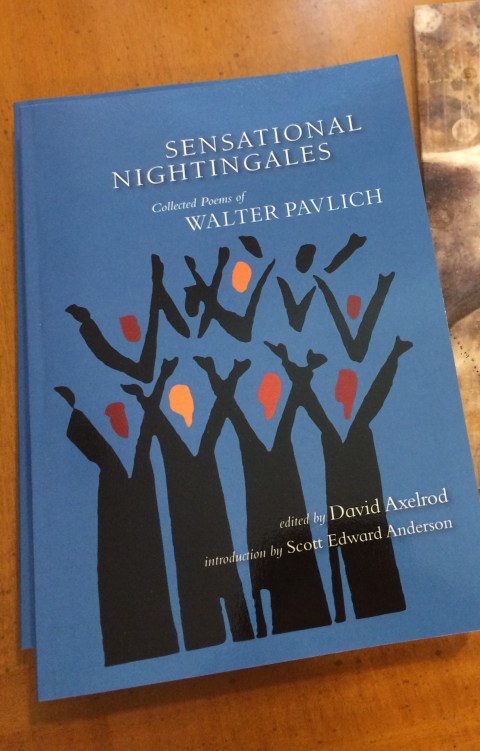

If you don’t know the poetry of Walter Pavlich, you now have the opportunity to explore his work in a new book, Sensational Nightingales: Collected Poems of Walter Pavlich, just published by Lynx House Press and edited by poet David Axelrod.

To whet your appetite, here is an excerpt from the Introduction I wrote for the book (the “Read more” link will take you to the full introduction as it appears on basalt):

“Writing is a way of saying you and the world have a chance,” poet Richard Hugo wrote. Hugo’s student, Walter Pavlich, once said in an interview, “I’ve always tried to define – and celebrate – sort of hard things in life. To try to find beauty in them – or to be more patient and watch the beauty unfold.”

Like Hugo, Pavlich wrote about the western landscapes he inhabited and the people he encountered there, and like Hugo, he was a regionalist in the best sense of the word: someone who knows the place where he lives and writes from that place well-observed.

Hugo’s influence, and by extension Theodore Roethke, with whom Hugo studied, is fairly evident in Pavlich’s work, especially the early poems. Yet, as his widow and soulmate Sandra McPherson wrote to me, Walter “was incredibly rich & rare & doesn’t merely sound like Dick Hugo at all; [he] also had subjects from his engaged life.”

Pavlich’s engaged life included work as a wildfire fighter, “smoke jumper,” and poetry teacher in prisons and schools. Born in Portland, Oregon, Pavlich graduated from the University of Oregon in Eugene and earned an MFA from the University of Montana, and his fondness for the forests and coastal environments of the Pacific Northwest of the United States pervades his poetry.

Something Sandra said to me also seems pervasive in Walter’s poetry: he had “a kind of spiritual isolation or loneliness he’s not explicit about.”

I think of Walter Pavlich as a “soulful traveler”… Read more

The Hamline University English Department recently conducted an in-depth Q&A with me about two of my poems, “Naming” and “Villanesca.”

Here is a link to their blog, Hamline Lit Link, where it was posted: Read more

The author’s copy of Riprap & Cold Mountain Poems by Gary Snyder.

Schuykill Valley Journal Online published my essay on Gary Snyder’s “Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout” last month. Here are the introductory paragraphs and a link to the full essay:

To get to Sourdough Mountain Lookout, you hike a good five miles, gaining 5000 feet or more of elevation. The terrain is rugged and the hiking strenuous, but that’s to be expected in the Northern Cascades. Located 130 miles northeast of Seattle, Washington, the Forest Service opened one of its first lookouts here in 1915.

The view from the lookout station, constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, is a postcard in every direction: Hozomeen Mountain and Desolation Peak looking north, Jack and Crater mountains out east, Pyramid and Colonial peaks to the south with Ross and Diablo lakes directly below, and, as if not to be outdone, the Picket Range is off to the west. This is impressive country and you can understand why it’s been an inspiration to poets and writers for generations.

Poet Gary Snyder was 23 when he worked as a fire-spotter on Sourdough Mountain in 1953.

My poem, “Becoming,” for John Ashbery’s 90th Birthday

July 28, 2017

Whatever you think of John Ashbery’s poetry — and there are opinions for and against, none of which I’m going to get into here — you cannot argue with the fact that he has been a presence in the word of Art and Letters since first emerging on the scene in 1956.

I have a soft spot for Mr. Ashbery, not necessarily because of his poetry or the fact that he hails from Rochester, New York, outside of which I spent my middle and high school years.

Rather, my fondness stems from his selecting one of my poems, “Becoming,” which is part of my Dwelling sequence and appears in my book Fallow Field, to represent the Millay Colony for the Arts, in its 30th Anniversary Exhibit at the Albany (NY) International Airport Gallery, in a juried show, from January-August 2004.

The poem, along with others in the sequence, was written during my residency at the colony in November 2002.

A heady feeling having my poem displayed in this context, adhesive red vinyl letters applied to the thick glass walls overlooking the security area. As I recall, my poem was positioned next to one by Colette Inez, another former resident at the colony, as a dear friend. In a way, it was a bit like being in an Ashbery poem.

(The photos here, blurry and boozily out-of-focus, seem to exemplify that feeling. And I had no idea my scarf was going to mimic the colors of the letters!)

Here is my poem, “Becoming,” with thanks to Mr. Ashbery — on this, his 90th birthday –for recognizing it in the way he did.

Becoming

Say that childhood memory

has more relevance than yesterday–

a moose calf curled up against the side of a house

merely saying it may make it so.

The way a sunflower towers over a child,

each year growing shorter–

a hermit crab crawling out of a coconut

–no, the child growing taller.

a sharp-shinned hawk swooping over a stubble field

imagining the earth, “the earth is all before me,”

blossoming as it stretches to the sun–

a brilliant red eft – baby salamander — held aloft in a small, pink hand

Is home the mother’s embrace?

a white cabbage butterfly flitting atop purple flox

The child sees his world or hers

stroking the furry back of a bumblebee

head full of seed, until it droops,

spent, ready to sow the seeds.

Say that our presence in the world

a millipede curling up at the child’s slightest touch

is making the book of our becoming.

–Scott Edward Anderson

Two Poems by Scott Edward Anderson in The American Poetry Review

Ben Franklin was wrong. Only death is certain; taxes fluctuate — and some even get away without disclosing or paying them.

Last April, my friend the poet A.V. Christie died. It was not entirely a shock, she’d been battling stage 4 cancer for several years, but the fact that she was my age and we’d shared a stage together reading our poems meant it hit close to home.

Four and half months before that, another poet friend, David Simpson, died. I last saw David reading his poems in New York, his book had just come out. He was seriously ill, but celebrating. That was a lesson for me to choose abundance.

Add to that the myriad of more well-known and lesser known poets who die in any given year and it starts to add up: Heaney, Angelou, Kinnell, Waring, Batin, Knott, Strand, Levine, Ritvo, Harrison, Williams, Lux, Tolan, Walcott…the list goes on.

All this death — certain, inevitable death — and a growing number of memorial services and poetry reading “remembrances” over the past few years prompted me do two things: 1.) I started celebrating living poets by acknowledging their birthdays and sharing one of their poems on Facebook; and, 2.) I wrote a poem that tried to shed a little humor on this dark subject.

The poem is called “Deaths of the Poets,” turning on its head the famous Samuel Johnson title, “Lives of the Poets.” I see it as a tribute to the poets who have passed and a kind of companion piece to my poem, “The Poet Gene.”

This poem borrows a few lines from the Lynyrd Skynyrd song, “Free Bird,” which I’ve always wished someone would shout out at one of my readings, as was done at concerts back in the 70s and 80s. (Imagine the lines read in “poet voice,” if you will.)

I threatened to shout for “Free Bird” if my friend the poet Alison Hawthorne Deming didn’t open a recent reading by singing a few bars of “Stairway to Heaven,” which is the title of her new book of poems. She did it brilliantly and I have photo evidence. Alas, no recording.

Here is my poem, “Deaths of the Poets,” which appeared in The American Poetry Review earlier this year:

Deaths of the Poets

Sweet sorrow then, when poets die,

as so many of them have this year.

Goodbye to them, as we linger

over their works, forgiving their deeds,

maleficent or magnanimous.

We remember their kind gestures,

wholesome smiles, constructive criticism,

and witty remarks over drinks or dinner.

We seldom recall what a bore they were at readings,

droning on about their poems or rushing through them,

or how they showed up ill-prepared,

rifling through papers trying to find

the exact poem they wanted to read next

or constantly looking at their watch

and asking the host or hostess,

“How much time do I have?”

Sometimes when I hear poets read in their “poet voice,”

I want to shout out “Free Bird,” like hecklers at old

rock concerts. “Play ‘Free Bird’!” ‘til they recite,

“If I leave here tomorrow

Would you still remember me?

For I must be traveling on, now

‘Cause there’s too many places

I’ve got to see.”

Sweet sorrow in their passing then,

poets gone this year and last and yet to come.

And in our mourning let us not forget

Seamus Heaney’s story about two Scottish poets

at a reading, one on the podium struggling

to find his poems and the other, seated in the front row,

saying, “When they said he was going to read,

I thought they meant read out loud…”

–Scott Edward Anderson

c) 2017 Scott Edward Anderson

First published in The American Poetry Review, Vol. 46, No. 01, January/February 2017

My poem, “Pantoum for Aceh” translated into Tamil by Appadurai Muttulingam, 2014.

A few years ago, my friend and former colleague at The Nature Conservancy, Sanjayan, introduced me to Tamil poetry after a long chat about poetry while we were both speaking at a conference in Aspen.

Sanjayan, a Sri Lanka-born Tamil, recommended I start with Poems of Love and War, selected and translated by A. K. Ramanujan, a remarkable book of Tamil poems from throughout history.

Long-time subscribers to my Poetry Month emails will recall I shared a few poems from the anthology in April 2009. Sanjayan sent my email to his father, Appadurai Muttulingam, who in turn sent me a copy of his own delightful book of short stories.

I responded by sending Appadurai a few of my poems (my book was not yet out) and he offered to translate one of them, “Pantoum for Aceh,” into Tamil for a Canadian-based Tamil-language journal, URAIYAADAL, which was published in 2014 (see photo above). He also sent me an anthology of contemporary poetry in Tamil, which I reviewed on my blog, here.

That post led the Sri Lankan Tamil poet known as ANAR (Issath Rehana Mohamed Azeem), whose poem, “Marutham,” I had called out in my review, to reach out to me earlier this year and send me some of her poems.

How small the world becomes when we are open to discovery and exploring cultures beyond our own. We are a global people and, I’m convinced, the movement to close our borders and shut out “foreign” cultures will soon die, because technology and travel and our future on this planet demands it.

ANAR has been writing poetry in Tamil since the 1990s. Her works include Oviem Varaiyathe Thurikai, Enakkuk Kavithai Mukam, Perunkadal Podukiren, Utal Paccai Vaanam, and Potupotuththa Mazhaiththooththal (a collection of Tamil folk songs from Sri Lanka).

A number of ANAR’s poems have been translated into English and published. Her books have won several awards, most notably the Government of Sri Lanka’s National Literature Award, the Tamil Literary Garden’s (Canada) Poetry Award, the Vijay TV Excellence in the Field of Literature (Sigaram Thotta Pengal) Award, and the Sparrow Literature Award.

ANAR writes regularly on her blog, anarsrilanka.blogspot.com (Google Chrome will translate it for you) and lives with her husband and son in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka at Sainthamaruthu.

Here is her poem, “The Brightness of Wind,” in an English translation by Professor Jayaraman and its Tamil original:

“The Brightness of Wind”

I allow the wind

To eat me

My eyes

I stroked its cool cheeks

For the first time

Before it showed itself in the wind

Intoxicated I drank the image day and night

Kisses I plucked from the wind

Overflowed as would the floods

These watery fingers

Reaching out from the wind

Play on my flesh

Tunes not known before

My dwelling has turned into a wind

You, the total haughtiness of the wind

You, the never-ending slight of the wind

The expanse of sand has gone dry with joy

Body, the green sky

Face, the blue moon

I saw the brightness of wind

In a flash of lightning

—ANAR

translated into English by Professor Thanga Jayaraman

And in the original (Not sure how the beautiful Tamil script will work in WordPress, we’ll see):

காற்றின் பிரகாசம்

காற்றைத் தின்னவிடுகிறேன்

என்னை …

என் கண்களை …

குளிர்ந்த அதன் கன்னங்களை வருடினேன்

முதல் முறையாக

காற்றில் வெளிப்படுமுன் பிம்பத்தை

பகலிரவாக பருகினேன் போதையுடன்

காற்றினுள்ளிருந்து எடுத்த முத்தங்கள்

வெள்ளமாய் பெருக்கெடுத்திருக்கின்றன

காற்றிலிருந்து நீளும் நீர் விரல்கள்

முன்னறியாத ராகங்களை

இசைக்கிறதென் சதைகளில்

என் வீடு காற்றாக மாறிவிட்டது

காற்றின் முழுமையான அகங்காரம் நீ

நீ காற்றின் முடிவற்ற அலட்சியம்

மகிழ்ச்சியில் உலர்ந்துகிடக்கின்றது மணல்வெளி

உடல் பச்சை வானம்

முகம் நீல நிலவு

நான் பார்த்தேன் காற்றின் பிரகாசத்தை

ஒரு மின்வெட்டுப் பொழுதில்

–ANAR

c) 2007 ANAR, used by permission of the author

(On a side note, you should check out Sanjayan’s new video series on Vox, made in conjunction with the University of California. Here’s a link: Climate Lab.)

Kicking the Leaves by Donald Hall, 1978

I began to write poems with some seriousness in my teens. During that time, I consumed as much poetry as I could get my hands on, devouring books like a beast impossible to satiate.

My high school English teachers, Richard Taddeo and Jack Langerak, fed that beast too. They paid attention to what I was reading, asked me questions, and suggested other books and poets in a kind of personal curation that predated Amazon’s algorithm by almost 30 years. (Taddeo also published my first poem to appear in print, a short couplet of little note, in the school literary magazine.)

It was Taddeo who gave me Donald Hall’s Kicking the Leaves, shortly after it came out in 1978. Hall’s poems in that book spoke to me. As a native New Englander, the landscape was familiar – Hall’s hardscrabble New Hampshire a good match to Frost’s flinty Vermont, where I’d summered as a child.

Donald Hall’s example in Kicking the Leaves – and hearing Elizabeth Bishop read her work later that fall — showed me a different path: I wanted to become a poet. A decade later, after I met Hall at one of George Plimpton’s Paris Review parties at the latter’s Sutton Place apartment, we began a correspondence.

I sent him poems. He wrote back, postcards mostly, which I knew from one of his essays were recorded by Dictaphone while watching Red Sox games from his blue chair in the same farmhouse described in Kicking the Leaves. He hated everything I sent him and told me so. This was good. Tough love was just what I needed. He helped me improve, revise, and be hard on my own work.

In the late 90s I gave a craft talk at the University of Alaska Anchorage as part of their Writing Rendezvous conference. In the lecture, which I called “Making Poems Better: The Process of Revision,” I examined many drafts of Hall’s poem “Ox Cart Man,” including the version that appears in Kicking the Leaves, and my own “Black Angus, Winter,” which was part of a group of poems that won the Nebraska Review Award in 1997. You can read it here.

Hall’s book – his 7th book of poems — came out when he was about to turn 50. My book, Fallow Field, came out as I turned 50, and includes “Black Angus, Winter” and several poems that Hall hated in earlier versions, all of which were improved by his terse, meaningful criticism.

You can find Donald Hall’s “Ox Cart Man” here (permission restrictions prevent me from publishing the poem in its entirety and an excerpt won’t do it justice) or better yet, buy his Selected Poems. And here is a recording of Donald Hall reading “Ox Cart Man.”

Dark Harbour Sunset, August 2016

For several years our friend, the poet Alison Hawthorne Deming, told us about Grand Manan Island off the coast of New Brunswick, Canada. Alison is a long-time summer resident on Grand Manan.

We finally made it up there last summer – and were we glad we did.

To say the island is a special place is a bit of a cliché and certainly doesn’t do the island justice. But then, when is a cliché not mostly true?

Remote and fairly difficult to get to from New York – you drive to the edge of Maine and keep going — Grand Manan sits on the western end of the mouth of the Bay of Fundy and was formed by colliding plates. You can see the fault line where Triassic and Cambrian rock meets.

Here time is marked by arriving and departing ferries, dramatic in-coming and out-going tides, and when the herring is running. The landscape is rugged basalt and a dense forest of birch and conifers, with pockets of wetlands, marshes, and rocky cliffs all formed and deformed by the sea, salt spray, and wind.

One evening before sunset, Alison took us over the top of the island to the other side, to Dark Harbour, a place that seemed somewhat stuck in time. I felt a bit like an intruder, although the place was oddly familiar as well, surrounded by encroaching darkness. There are rumors of pirates or a pirate curse in Dark Harbour.

Dark Harbour is also the dulse capital of the world. Dulse is an edible seaweed harvested by hand at low tide and dried in the sun outside during the summer months. Grand Mananers love their dulse, which seems a healthy substitute for chewing tobacco or potato chips. Dulsers are a special breed, as this video from Great Big Story attests: http://www.greatbigstory.com/stories/dulser-dark-harbor

Several poems in Alison’s new book of poems, STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN, feature the people and landscape of Grand Manan. There are echoes in these poems of another Canadian Maritime setting by another poet from New England with Maritime ties, something about the cold and crystal clear water, a quiet observation and an older way of life, the dark forest and the sea.

We’re going back this summer.

Here is Alison Hawthorne Deming’s poem, “Dark Harbour”:

“Dark Harbour”

Dulse camps teeter on cobbled basalt

where storms have heaped a seawall

topped with tumult of silvered

wharf timbers and weir stakes

enough driftwood scrap to salvage for a shack

paint the battered door dusty blue.

A rusty slatted bed kerosene pooled

in a glass-chimney lamp waiting for a match

dirty teapot on the camp stove

it’s home for a night or two

when tides are right for gathering.

Stone slips wait gray and smooth from wear

where yellow dories are winched and

skidded to motor offshore headed

for the dulsing ground. A man

who works the intertidal shore

says I can smell the tide coming in.

I raise my face to the wind to try to catch

what he knows. Cold and crystal clear

the water laps the rocks and rattles them

as it recedes. The man pulls fistful

of purple weed off tide-bare rocks

a gentle rip sounding with each pull

the ribbons gathered in his basket

dark as iodine deep as hay scythed

and piled in ricks harvest picked by hand

gathered from the transmutation of light

that sways at high tide like hair in the wind

and lies still for combing when the tide recedes

cropland where sea and rock do the tillage.

–Alison Hawthorne Deming

c) 2016 Alison Hawthorne Deming. Used by permission of the author.