by François-Xavier Fabre (1800)

Life in America today feels chaotic—unmoored, even. Not long ago, we were enjoying the strongest post-pandemic economy in the world and, for all our flaws, still held a place of trust and respect among nations. Now, it feels as though we’re in retreat from the very values that have defined us for nearly 250 years. Our economy is shaky, our moral compass seems scrambled, and our global standing has taken a nosedive. Former allies are pushed aside, while historic adversaries are reframed as potential friends. How the heck did we get here?

For some time now, I’ve felt we’re living through the final convulsions of an outdated, constricted worldview—a last gasp, if you will. The future, by contrast, looks vibrant in its diversity, and stronger for it. But the old mindset is panicking. It scapegoats the “other” for its own decline, retreats into fear, and recoils from empathy, love, and peace. It would rather enforce authorityrrany—a toxic blend of authoritarianism and tyranny—than allow for genuine autonomy. In clinging to control, it seeks to impose a narrow minority’s will on a richly diverse majority.

Still, the tide is too strong against it. I believe the day will come when we look back on this era and see it clearly for what it was: a necessary darkness before the dawn. As poet Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) wrote, “the longed-for tidal wave of justice” will break, and when it does, it will wash away the debris of this fearful, closed-off way of thinking.

That famous line comes from Heaney’s The Cure at Troy, his poetic reimagining of a play by the ancient Greek dramatist Sophocles. The work wrestles with questions of morality, deceit, political compromise, suffering, and the hope of healing. Heaney’s brilliance lies in how he connects these ancient themes to the struggles of our modern lives. Lately, I’ve been thinking often of the stanza containing that “tidal wave” line—and the even more quoted line about hope and history rhyming. I decided to revisit the full passage, and what I found feels especially fitting in these troubled times:

From The Cure at Troy

Human beings suffer,

They torture one another,

They get hurt and get hard.

No poem or play or song

Can fully right a wrong

Inflicted and endured

…

History says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracles

And cures and healing wells.

Call miracle self-healing:

The utter, self-revealing

Double-take of feeling.

If there’s fire on the mountain

Or lightning and storm

And a god speaks from the sky

That means someone is hearing

The outcry and the birth-cry

Of new life at its term.

It means once in a lifetime

That justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

—Seamus Heaney

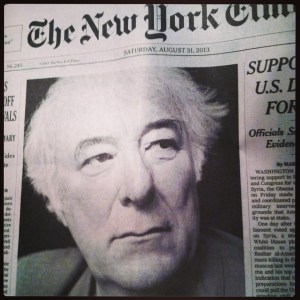

Seamus Heaney Remembered

November 12, 2013

A stellar lineup of poets, musicians, publishers, and poetry organizations gathered last night to pay tribute to Seamus Heaney.

Heaney, the 1995 Nobel laureate in literature, died after a fall on Friday, August 30, 2013, in Dublin. He had suffered a stroke in 2006.

The event, organized by the Poetry Society of America, the Academy of American Poets, Poets House, the Unterberg Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y, the Irish Arts Center PoetryFest, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Heaney’s US publisher, took place at the Great Hall of Cooper Union in New York City, an appropriate venue for such a stentorian public poetic figure.

Among the readers were Heaney’s fellow Irish poets Eamon Greenan, Eavan Boland, Greg Delanty, and Paul Muldoon, along with Tracy K. Smith, Kevin Young, Jane Hirshfield, and Yusef Komunyakaa. You can read the full list here: Heaney Tribute.

One poem that was missing last night was one that I thought of shortly after hearing the news of Heaney’s death.

We were heading out to Martha’s Vineyard for a week with Samantha’s family to celebrate the 70th year of her mother, Lee Langbaum. The New York Times the morning we left had Heaney’s picture on the front page and ran his obituary, but I couldn’t get to it until much later in the day, aboard the ferry.

It was sad news indeed, for those of us who loved his poetry and for the world that lost a remarkable voice. Heaney was a wonderful poet and a warmhearted man, as most of the people gathered at Cooper Union last night — whether on stage or off — would attest.

I only met him twice, and only very briefly after readings, but he was gracious and generous both times. The last time I saw him was at a reading three years ago or so at Villanova University.

The poem that came to mind on Martha’s Vineyard, came to me as we were talking with the oyster shucker outside of Home Port Restaurant in Menemsha. Of course it was “Oysters,” a poem that was missing last night.

Here is Seamus Heaney’s “Oysters”:

Our shells clacked on the plates.

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades

Orion dipped his foot into the water.

Alive and violated,

They lay on their bed of ice:

Bivalves: the split bulb

And philandering sigh of ocean —

Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered.

We had driven to that coast

Through flowers and limestone

And there we were, toasting friendship,

Laying down a perfect memory

In the cool of thatch and crockery.

Over the Alps, packed deep in hay and snow,

The Romans hauled their oysters south of Rome:

I saw damp panniers disgorge

The frond-lipped, brine-stung

Glut of privilege

And was angry that my trust could not repose

In the clear light, like poetry or freedom

Leaning in from sea. I ate the day

Deliberately, that its tang

Might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

—Seamus Heaney, 1939-2013

Here is Heaney reading his poem at the Griffin Poetry Prize Awards ceremony in 2012: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xslwsp_seamus-heaney-oysters_creation

Another poet from across the Pond for this week. British poet Jo Shapcott was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004. She once described how the treatment left her feeling “reborn as someone slightly different.” Last year, she published a collection that emerged from this experience, Of Mutability.

“The body has always been a subject for me,” she told The Guardian in an interview. “It is the stage for the high drama of our lives, from birth to death and everything in between. When you observe your own body under physical change like that, there’s a new kind of urgency. I had a lumpectomy, my lymph glands out, chemo and radiotherapy. You go through several different stages, so you don’t know how ill you are for a while, and the verdict keeps getting worse and worse, until you can actually take action, start treatment.”

The concept of mutability has a long tradition in English poetry extending back as far as Chaucer. Mutability points to the transience of things and of the inevitable changes of life.

Wordsworth spoke of “the unimaginable touch of Time” in his poem, “Mutability.” Shelley ended his poem of the same title,

It is the same!–For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

Shapcott is no stranger to life’s mutability. Her parents both died unexpectedly when she was 18. She found solace in the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop, who had also suffered early loss and dramatic change throughout her life. Shapcott went to Oxford to pursue a PhD on Bishop’s poetry, but left for Harvard to study with poet Seamus Heaney when she received a scholarship. It turned out to be a fortuitous mentorship.

Her books include Electroplating the Baby (1988), Phrase Book (1992), My Life Asleep (1998), and Her Book: Poems 1988-1998 (2000).

Shapcott writes with a “‘rangy, long-legged’ brio,” as one critic described her tone. Her language is equally intellectual and sensual, enigmatic and direct, which makes for poetry of breadth and range. Consequently very few poems feel alike in the way you can tell the work of certain poets, a Gary Snyder poem or a Billy Collins poem, for example. (The one exception in Shapcott’s work is her “Mad Cow” persona poems.)

Like Bishop, Shapcott is rarely overtly personal, even when writing about her illness from which she is now, thankfully, fully recovered and working on a new book.

Here is Jo Shapcott’s poem, “Of Mutability”:

Too many of the best cells in my body

are itching, feeling jagged, turning raw

in this spring chill. It’s two thousand and four

and I don’t know a soul who doesn’t feel small

among the numbers. Razor small.

Look down these days to see your feet

mistrust the pavement and your blood tests

turn the doctor’s expression grave.

Look up to catch eclipses, gold leaf, comets,

angels, chandeliers, out of the corner of your eye,

join them if you like, learn astrophysics, or

learn folksong, human sacrifice, mortality,

flying, fishing, sex without touching much.

Don’t trouble, though, to head anywhere but the sky.

–Jo Shapcott