Writing for posterity may be as old as writing itself. Poets, novelists, essayists, and philosophers all write with the hope that their work will survive them — even if they deny it — living on to touch new readers in distant ages.

Writing for posterity may be as old as writing itself. Poets, novelists, essayists, and philosophers all write with the hope that their work will survive them — even if they deny it — living on to touch new readers in distant ages.

Some writers never lived to see their work gain an audience or even a small, devoted readership. Some, like Robert Browning, obsessed about it.

Alas, the quote from Walter Lowenfels that adorns this blog is a daily reminder to me of the fate of almost all of us.

How much of our writing will survive, will last, will live to find readers throughout our lifetime and beyond?

I was struck by this question twice this week.

The first was Tuesday night, having dinner with twin brother poets Dan and David Simpson. We were talking about the fact that none of the three of us had published collections of our work, despite “success” placing individual poems in journals and magazines, and the awards and accolades we’ve received over the years.

David told of an encounter with a writing mentor who reviewed his draft manuscript. The mentor suggested they each go through the script and rate the poems numerically: 1, 2, 3; then they would compare the results and see what came of it.

My friend was dumbfounded that the mentor found so few 1s among the collection — really only a few — and only a few 2s as well. The 3s weren’t even worth mentioning and probably should be discarded, suggested the mentor.

Bruised as David’s ego was by the experience, I found some solace in it.

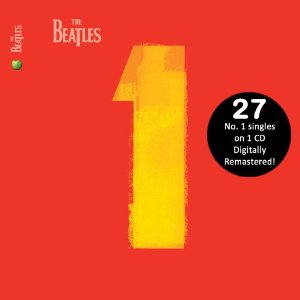

“How many #1 singles did The Beatles have?” I asked David. (27 is the answer.)

“So, okay, we can agree that none of us are The Beatles,” I offered. “But we could be, say, The Guess Who.” (That group had only had one number 1 single, “American Woman,” for three weeks May 9 -29, 1970, yet we all know the song and you probably have it streaming in your head right now at its mere mention.)

We agreed that we would be lucky to have one “hit” poem continue to be read by people after our deaths. We’d be delighted if a handful survive us, yet it’s helpful to have some perspective.

A few days later I received a request for permission to reprint a piece of writing I did in 1993. This is the most widely reprinted thing I’ve written and, I’m afraid, will likely survive any and all of my creative work.

The piece is a review of N. Scott Momaday‘s In the Presence of the Sun: Stories and Poems, 1961-1991 that I wrote for The Bloomsbury Review. I have had more requests to reprint that one 1500-word review than any other piece of writing I have done — ever.

It’s even been made available for students on such services as eNotes: Scott Edward Anderson (review date 1993).

I re-read the piece this morning — it’s not a bad piece of writing, as reviews go, and certainly lives up to eNotes’ description: “Anderson provides a thematic and stylistic review of In the Presence of the Sun.”

Yet, when I wrote the review, I never imagined it would be my most cited, most reprinted, perhaps even my most read piece of writing.

If only the strong survive may this piece rock on.

John Lennon at 70

December 8, 2010

- Image via Wikipedia

The Beatles Story, a Liverpool Museum devoted to the Fab Four and that British city’s favorite sons, held a poetry contest this fall in honor of John Lennon.

John would have been 70 years old on October 9, 2010, had he not been gunned down by a psychopath 30 years ago today.

The contest rules were simple: 40 lines on Lennon for his 40 years on Earth. I entered, but didn’t win the contest.

And although it may ruin my poem’s chances of being published in The New Yorker (to whom I’ve recently submitted it — forgive me, Paul Muldoon), I’ve decided that it’s important for me to share it with you on this day when so many of us are remembering John.

Here is my poem:

John Lennon at 70

“The streets are full of admirable craftsmen,

but so few practical dreamers.”–Man Ray

Lennon, the boy, practically an orphan;

Chip on his shoulder, mad at the world.

Lennon, the teenager, the rocker, the mocker,

Hard-driven, jealous, troublemaker, and bold.

Lennon, the young man, an edge to his attitude

And confident swagger; “To the top Johnny!”

Lennon, maturing, tightening up, melodic,

But still biting, sardonic, coming into his own.

Lennon, twenty-five, songsmith; honest, open, real.

A turning point: meeting drugs and Dylan.

Lennon, experimenting, laying down tricks

Rather than tracks; quirky, artistic, obscure.

Lennon, twenty-eight, life changed by a “Yes.”

Branching out, becoming an Artist.

Lennon, approaching thirty, back to his roots;

Raw, stripped-bare, primal screaming J.

Lennon, early 30s, getting political in the N-Y-C,

Under the influence; message trumping music.

Dr. Winston O’Boogie, mid-30s, recapturing

Some of the old magic, putting aside mind games.

Mr. Lennon, “retired,” house-husband, baking

Bread and raising a son; “just watching the wheels…”

Lennon, stretching out, almost forty,

Enjoying writing again, for himself and for Sean.

Lennon at 40, middle-age for most, a new record out.

He’s done more than many at this age or older, even.

Lennon, talking to his audience of survivors,

“We made it through the seventies, didn’t we?”

Lennon, walking in Central Park with Yoko.

“It’s John Lennon I can’t believe it…”

Lennon letting his guard down,

A new sense of purpose, renewal, direction—

Lennon, at 40, dead in his doorway.

“I read the news today, oh boy…”

Lennon’s life: meteoric, troubled, brilliant,

Full fathom flaming—

Lennon at 70: would he be a grumpy old man,

Still on the stage — or both? We’ll never know.

I read the news today and think: We need him;

Then hear John’s voice, singing “Love is all you need.”

–Scott Edward Anderson

On John Lennon’s “Help!”

October 9, 2010

- Cover of John Lennon

The debate about rock lyrics and poetry has been going on for decades. Ever since Bob Dylan hit the scene in the early ’60s and songs started to be about more than dance moves, teenage love, and holding hands.

The Beatles started to break out of that mold in late 1964 through 1966 with their principle songwriters — perhaps the greatest songwriting team ever — John Lennon and Paul McCartney branching out into new sounds and new concerns.

Lennon, who would have been 70 today, started writing more personal, introspective songs, clearly showing the influence of Bob Dylan. And McCartney wrote two of his most poetic songs in this period, “Eleanor Rigby” and “Yesterday.”

While Lennon songs like “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” “Nowhere Man,” “In My Life,” and “Norwegian Wood,” are often cited as revealing the more personal John, it is with “Help!” that I think John really puts himself on the line.

Recorded in April 1965, it was, according to some accounts, a throw-away; something John had to dash off after the film they were working on had been renamed.

But John himself revealed in 1980’s Playboy interview with David Sheff that “I was actually crying out for help. Most people think it’s just a fast rock ‘n roll song. I didn’t realize it at the time…but later, I knew I really was crying out for help.”

When I was younger, so much younger than today,

I never needed anybody’s help in any way.

But now these days are gone, I’m not so self assured,

Now I find I’ve changed my mind and opened up the doors.Help me if you can, I’m feeling down

And I do appreciate you being round.

Help me, get my feet back on the ground,

Won’t you please, please help me?

Despite its jaunty pop melody and speed, the song is really a plaintive poem that has a maturity beyond the author’s then 24 years.

“It was my fat Elvis period,” Lennon told Sheff. He was “very fat, very insecure, and he’s completely lost himself. And I am singing about when I was so much younger and all the rest, looking back at how easy it was. Now I may be very positive… yes, yes… but I also go through deep depressions where I would like to jump out the window, you know. It becomes easier to deal with as I get older; I don’t know whether you learn control or, when you grow up, you calm down a little. Anyway, I was fat and depressed and I was crying out for help.”

He was seemingly on top of the world, had everything he imagined he wanted from the group’s early days. And yet, seeing himself from outside himself, John the vulnerable man sees Beatle John and recognizes things are not all they seem.

And now my life has changed in oh so many ways,

My independence seems to vanish in the haze.

But every now and then I feel so insecure,

I know that I just need you like I’ve never done before.

Lennon told Jann Wenner in Rolling Stone in the 1970 Rolling Stone interviews, that it was among his favorites “Because I meant it — it’s real. The lyric is as good now as it was then. It is no different, and it makes me feel secure to know that I was that aware of myself then. It was just me singing “Help” and I meant it. I don’t like the recording that much; we did it too fast trying to be commercial.”

The music is a mask of sorts, then, and perhaps John wasn’t quite that comfortable showing how insecure he was at the top of the pop world. But isn’t that what makes songs like “Tears of a Clown,” and Lennon’s own “I’m a Loser” so great?

Songs like “Help” reveal a vulnerability we all feel, but help us get past it through the sheer joy of the music and recognition that we’re not alone.

And really, I think that’s the mark of true genius, whether as a poet, musician, or pop star.

On rejection and persistence

April 25, 2009

“Rejected is such a harsh word….I prefer…declined,” a friend wrote to me after I Twittered about a recent rejection.

While I appreciate her sentiment and her affection, a rejection by any other name still smells not sweet.

I’ve started to send out a manuscript of poems again, after a few year hiatus. I’m targeting a select list of publishing houses that have open submission periods. So I need to steal myself against rejection, knowing how few books of poetry get published each year.

There are a few first book contests I’ll probably enter as well (I’ve come close a couple of times with an earlier iteration of my ms), but the fees have gotten higher and I’m not convinced that’s the way to go.

It’s been awhile since I’ve had either the time or inclination to submit, but I’ve worked over this manuscript quite a bit these past few years.

I have sent it — or a slightly different version — to two poets with whom I’ve studied or worked in the past, and they have both said it’s ready. And the bulk of the poems have been published in journals or magazines, both in print or online.

Nothing prepares you for rejection, however. When that note comes in the mail or over email it is still like a slap in the face. And yet, as another friend once told me, you need to just look up who is next on the list and send it out to them. It’s like an assembly line.

So, I accept that a certain publisher didn’t find room on its list for an important first book, that they rejected it or declined to take it on, and I’ll move on to the next on the list.

Launching a Poetry Blog for National Poetry Month

April 16, 2009

I’ve decided to launch a new poetry blog for National Poetry Month. Here I will post some of my favorite poems, selections from the past 12 years of my National Poetry Month emailings, and other poetry related posts.